Why you wouldn't fly Air Kessler

The economics look appealing. So why do all-business class airlines keep failing?

This is nice, isn’t it? Sitting in your airline branded pyjamas, sipping mid-range champagne and fantasising about the jolt of serotonin your brain will release as you hit that recline button to lie perfectly flat. “If there’s anything I can do to make your journey more comfortable, please don’t hesitate to let me know”, the flight attendant says as she hands you a hot towelette.

Well, there is one thing, you murmur to yourself. Do I have to watch the riff-raff traipse past and towards the back of the plane, what with their bulging neck pillows and glottal stops? Sure, the economy cabin is separated off by a flame-resistant polyester curtain. But is that enough? You can’t afford to go private — you’re not that level of rich. Plus, there are the carbon emissions. So what about an all-business class airline?

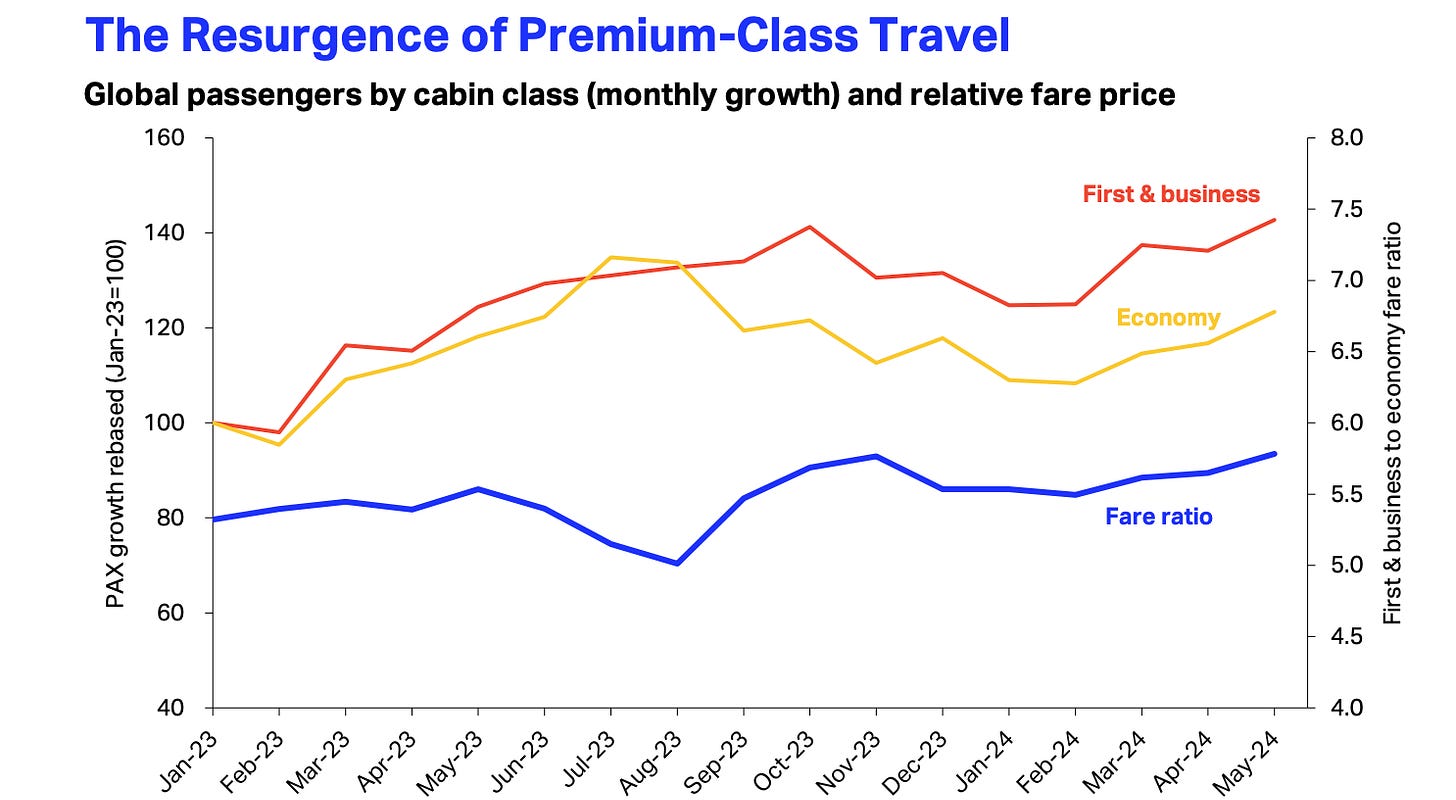

Many an entrepreneur has had the same thought. And it is not difficult to understand why. Business and first class contributed about 20% of total passenger revenues on average between 2011 and 2019, rising to 30% on international routes. That is despite representing just 7% of total revenue passenger-kilometers, according to the International Air Transport Association, the aviation trade body.

And the future appears even more lucrative. By the end of 2023, while traffic in economy had reached 94.1% of pre-Covid levels, for premium cabins it was at 99.1%.

So, there we have it. The economics of all-business class airlines must be an invitation to print money. Perhaps I will be welcoming you aboard Air Kessler? Well, you can probably guess what’s coming now.

Mo Money Mo Problems

Notwithstanding the obstacles all new airlines face, from start-up costs to unfavourable economies of scale, the first difficulty for Air Kessler will arrive in the form of route networks. There are only so many destinations that can support an all-business class model. Sure, there’s London to New York, Paris to Dubai and Tokyo to Hong Kong. But what about big cities to medium markets?

Moreover — and this is just for my fellow aviation nerds — you may have noticed I said ‘London’ but failed to specify an airport. People flying business class on actual business will have a strong preference for Heathrow over Gatwick, let alone Stansted or Luton. And good luck securing a slot from the world’s most slot-constrained airport1.

Even on routes like London to New York, many business-class passengers are simply connecting. They're not flying point-to-point, but originating in places like Buffalo and ending up in Leeds. That means a successful airline needs a broad network or strong partnerships — something a boutique carrier like Air Kessler won’t have.

What’s the points?

Alright, so Air Kessler is going to be highly selective on its routes. That’s smart. But it also means we’re limiting ourselves to a tiny sliver of the market. And here we run into even more problems.

Major airlines run on points, miles and credit cards. In fact, frequent flyer programmes have become the most profitable part of the industry. Think of the British Airways American Express card, the AAdvantage Executive World Elite Mastercard or the Delta SkyMiles Reserve. These airlines are more like banks.

Delta, for example, made $6.8bn from its AmEx partnership in 2023. These programs don’t just pad profits, they lock customers into loyalty ecosystems. For a new airline unable to offer passengers the opportunity to earn and burn, that’s an enormous competitive disadvantage — one many status-conscious travellers won’t be able to stomach.

What if things go wrong?

It’s five o’clock in the morning and you get the dreaded text from British Airways: your flight has been cancelled. Well, the good news at least is they’ve offered to book you on a flight leaving two hours later. You’ll miss out on a bit of sightseeing but still make your meeting.

Conversely, if Air Kessler cancels on you — say, due to mechanical problems — you are stuck. We don’t have any spare aircraft waiting around. You’ll either have to fly tomorrow, or scramble for a last-minute seat with a competitor. This sort of operational fragility is also what makes boutique airlines vulnerable in economic downturns.

Back in the 2000s, a number of all-business class airlines — including EOS, SilverJet and MaxJet — promised a new golden age of premium travel, only to be promptly grounded by the Global Financial Crisis. Their downfall was as much about structure as timing.

While larger airlines have greater scope to absorb losses and flex their operations towards price-conscious economy travellers or cargo, all-business class models target a narrow, fickle segment of the market with sky-high expectations and a low tolerance for disruption — all in an industry famous for paper-thin margins.

Unless you have deep pockets, exceptional luck or some truly unique value proposition, the economics just don’t fly. Airlines such as La Compagnie may still be going, but don’t expect to board Air Kessler anytime soon.

Back in 2016, Oman Air was reported to have paid $75m for a pair of slots at Heathrow