Andrew Bailey's Hugh Grant moment

Bank of England Governor takes swipe at Trump's trade war

Love, Actually is a bad film, made irredeemably worse by the many ensemble-but-unrelated-yet-ultimately-intertwined-vignettes-often-set-during-Christmas facsimiles it spawned over the following decade. This is not to damn all Richard Curtis productions — Notting Hill remains my generation’s Citizen Kane. But I said what I said.

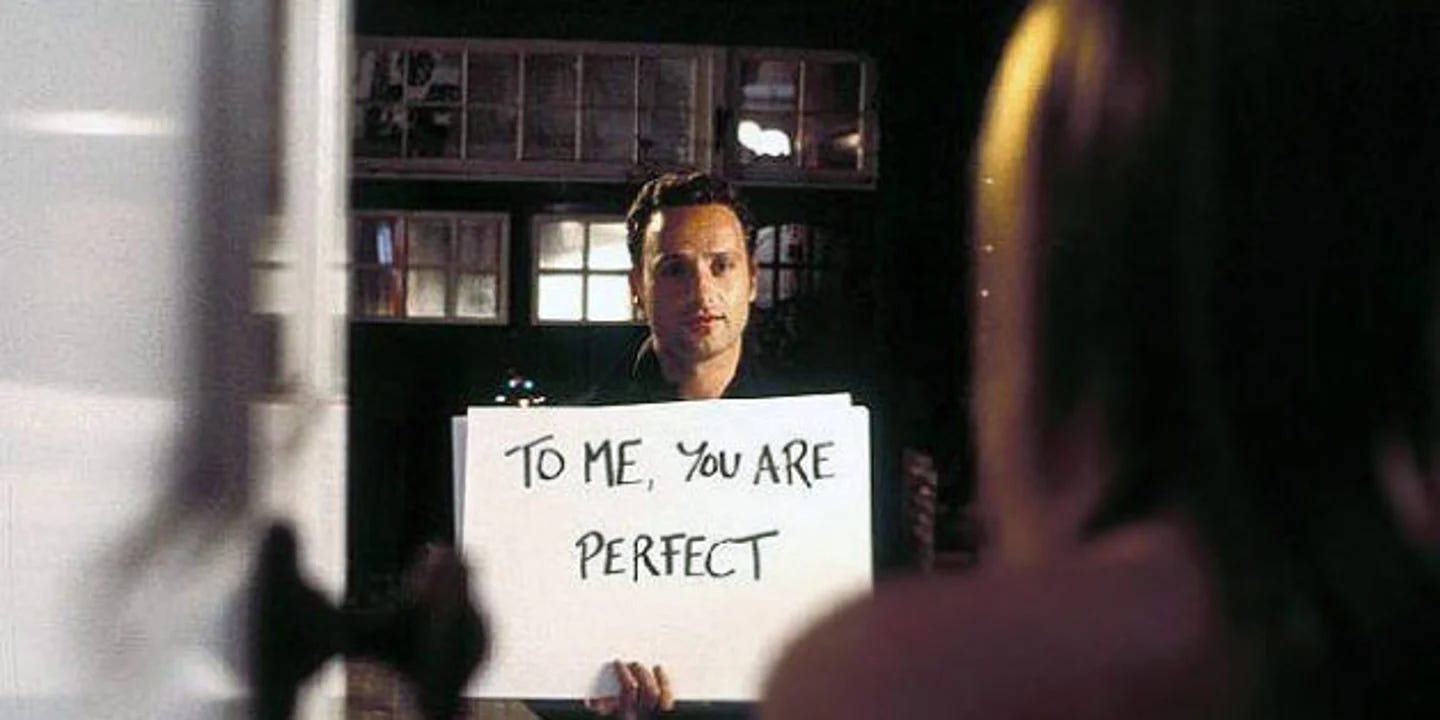

Its most grating scene — and this is a high bar, I concede — is also its most famous1. The prime minister, played by Hugh Grant, torches the special relationship because, from memory2, the US president flirted with his secretary — an eruption of indiscipline that would have made even Boris Johnson blush.

Things went meta two years later when Tony Blair, something of an inspiration for Grant’s character (and, indeed, us all) referred to this oft-celebrated moment in his 2005 address to the Labour Party conference. Speaking on the value of diplomacy and the importance of looking beyond short-term headlines, Blair said:

I know there's a bit of us that would like me to do a Hugh Grant in Love Actually and tell America where to get off. But the difference between a good film and real life is that in real life there's the next day, the next year, the next lifetime to contemplate the ruinous consequences of easy applause.

At this point, and having alienated my entire readership, I turn to Andrew Bailey’s address to the Financial and Professional Services Dinner, with the catchy title: The future of the multilateral economic system and some news on the UK payments infrastructure — also known as the Mansion House speech3.

The room was, as usual, filled with the great and the good — senior bankers, company bosses and, of course, the Lord Mayor. Also in attendance was US Securities and Exchange Commissioner, Hester Peirce. Now, as Governor of the Bank of England, Bailey is always hyper-vigilant over his choice of words. This is a man who can move markets at the drop of an adverb. So it was rather intriguing what he chose to say.

Bailey did not go the full Grant, but he went further than many world leaders — including Keir Starmer — have been prepared to go in criticising US policy. First and foremost, he undertook a wholehearted defence of the multilateral system. That is, institutions such as the IMF, World Bank and WTO, as well as multi-country decision-making bodies like the G7 and G20. These matter, he stressed, because they underpin the pursuit of economic growth and stability through co-operation.

Then, he turned to the issue of growing global imbalances, identifying China’s weak domestic consumption rate as one such example. But he sharply warned against the US using tariffs as a means to reduce its trade deficit. “I say this,” he began, “in the spirit of constructive challenge and engagement.” Which is the central bank talk for ‘no disrespect.’

Increasing tariffs creates the risk of fragmenting the world economy, and thereby reducing activity. We can go back to Adam Smith and his contemporaries for the insight that trade expands activity by enabling specialisation, knowledge and technology sharing and productivity growth.

After a further robust defence of the rules-based trading system, Bailey then set out four proposals for reform, before adding how much he agrees with US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent about things. Then, he went for it:

The rules of the process have to be accepted and the imposition of rules by one player, however dominant, isn’t a recipe for sustained stability.

There is good reason why neither the prime minister nor chancellor would give this speech and why Nato general secretary Mark Rutte seemingly spends his days spouting Euripides fan fiction involving Donald Trump. But Rutte is a diplomat. So, in international affairs, is Starmer.

Bailey has a little more wriggle room. He may not be allowed to casually speculate about what interest rates will be in six or 12 months’ time, but multilateralism = good, tariffs = bad? For a central banker, that is just stating the blindingly obvious. And so, Andrew:

Perhaps alongside the one where Alan Rickman makes Emma Thompson cry while Joni Mitchell’s Both Sides Now plays (there is more real sugar in a sachet of Sweet’n Low)

Unlike Back to the Future, I have seen Love, Actually — albeit not since the George W. Bush administration

I also watched Rachel Reeves’s speech. It was really boring