Personalised pricing is already here

Look to your left, look to your right and ask: how much did you pay?

Long before shrinkflation, ingredient substitution and soaring cocoa prices, there was differential pricing. Essentially, unscrupulous shopkeepers would charge their wealthier customers more than poorer ones for luxury items such as chocolate. To combat the practice, Cadbury began putting the price directly on the wrapping. It proved an exceptionally popular decision.

The idea that everyone should pay the same price for the same item is deeply ingrained in the collective consumer mind. But from a business perspective, this is deeply unsatisfactory. To maximise profits, it surely makes sense to sell goods and services at the highest price each customer is prepared to pay?

For that reason, price discrimination is everywhere. Sometimes, we barely notice it because it feels fair and reasonable (peak and off-peak Tube travel). Other times, it feels fair but unreasonable (hotels charging vastly more for rooms during school holidays). And at other times, it feels neither fair nor reasonable (Uber surge pricing during extreme weather events). At which point, companies under fire tend to make a strategic retreat.

Earlier this month, Delta Airlines revealed it was using artificial intelligence (AI) to determine the prices of some of its domestic flights, with the aim of increasing its usage from 3% to 20% by the end of this year. However, following sharp criticism from lawmakers and broad public unease, the airline later clarified it would not use AI to set personalised ticket prices.

What is curious is that airlines already engage in price discrimination all the time. Wherever you sit on a plane, the passenger next to you almost certainly paid a different sum. Of course, there are some obvious factors that determine ticket prices, from demand for travel to length of flight. But it goes far beyond that.

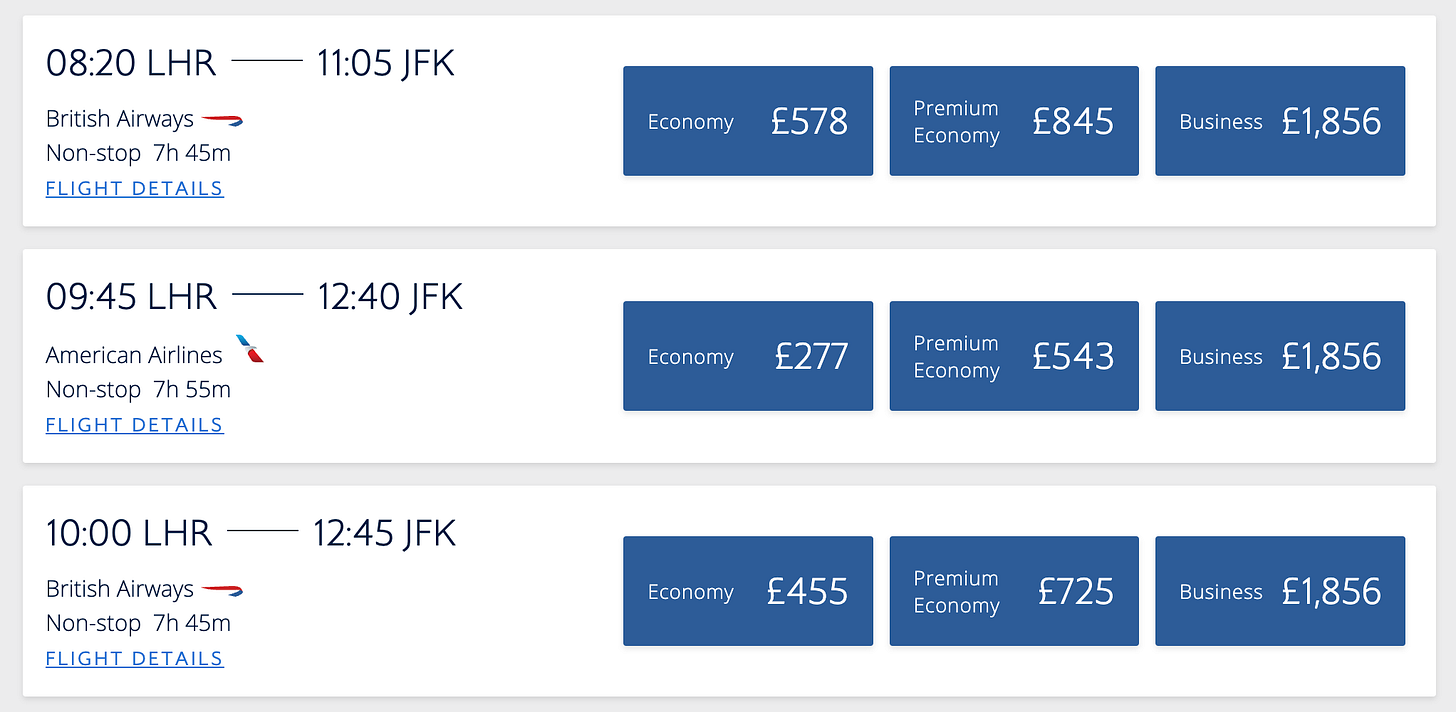

For example, you will usually pay more to fly direct than with a one-stop. Take a look at the below flights with British Airways on 22 October. The first is direct from London to New York.

The second is Amsterdam to New York via London. As you can see, nearly every option is cheaper, even though British Airways is having to fly you further, using more fuel, food and staff. But flying direct is a convenience people are prepared to pay a premium for. Changing planes at Heathrow is deeply annoying.

Long before Hillary Clinton’s “basket of deplorables”, there were airline pricing buckets. As the cheaper ones filled up (think the class £9 Ryanair ticket to Rome), the next appeared. Then, there is real-time dynamic pricing. As the name suggests, this involves airlines offering prices to their customers based on contextual information. This is not necessarily personal data, but rather information built on elements including length of stay, date of departure and competitor pricing.

This practice has been around since the 1980s but airline revenue models have grown increasingly sophisticated over the years. In fact, they now have the ability, in the words of the International Air Transport Association (IATA), to “adjust the price in real time without needing to file fares with a third-party system.”

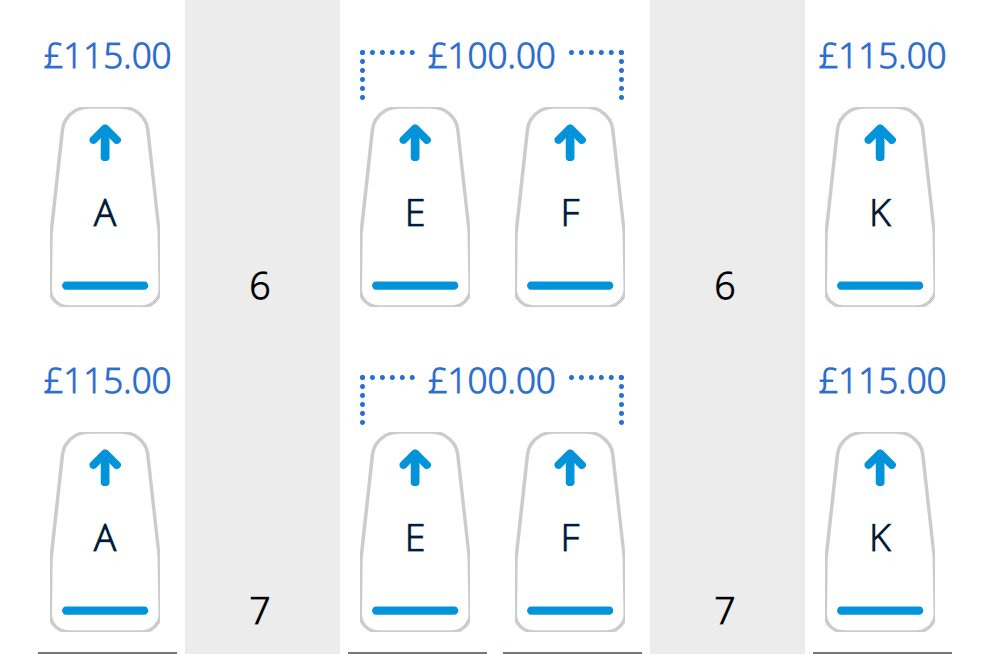

But now we go deeper. German carrier Lufthansa was one of the first to adopt continuous pricing, which enables it to offer not just price buckets but indefinite price points. As the airline puts it, “A price offer is unique to the booked itinerary at the moment of request.”

What can passengers expect in the future? We now need to talk about dynamic bundling. This is common in the retail sector, where offers are generated dynamically, depending on consumer profile and context. The next step, according to IATA, is real-time interaction between airline and customers via (health warning) “conversational commerce” such as digital assistants and chatbots.

This will better enable customers to pick and choose their own bundles or transmit additional contextualised information to the airlines. The more information is shared between the parties the better the offers can be personalised: it requires trust of the customer with the airline that can now stay in contact through the entire journey.

Fundamentally, this is centred around a simple phenomenon: airlines using new technologies to better understand each customer’s willingness to pay in pursuit of filling an aircraft at the highest possible price. And they have grown extremely good at it. But it still relies in large part on the absence of transparency — like workplaces which assume colleagues will discuss everything except how much they are paid.

Delta faced a PR disaster for its move into AI and pulled back. I expect they’ll try again before long and no one will much notice.

Then there are cookies. If you go on the booking system and look at a flight, but don't book it, it will probably be dearer if you look the next day. This has even happened to me recently, hiring vans from Enterprise. I booked a big van for a surprisingly reasonable £50 or so. A few days later, I realised I needed a small van for a day. Went back on the site and a small van was £80. Deleted Enterprise cookies from my browser, and all of a sudden it was £40.