The crash that never ended

Forget Brexit. It was the 2008 financial crisis — and the era of cheap money — that truly shaped modern Britain

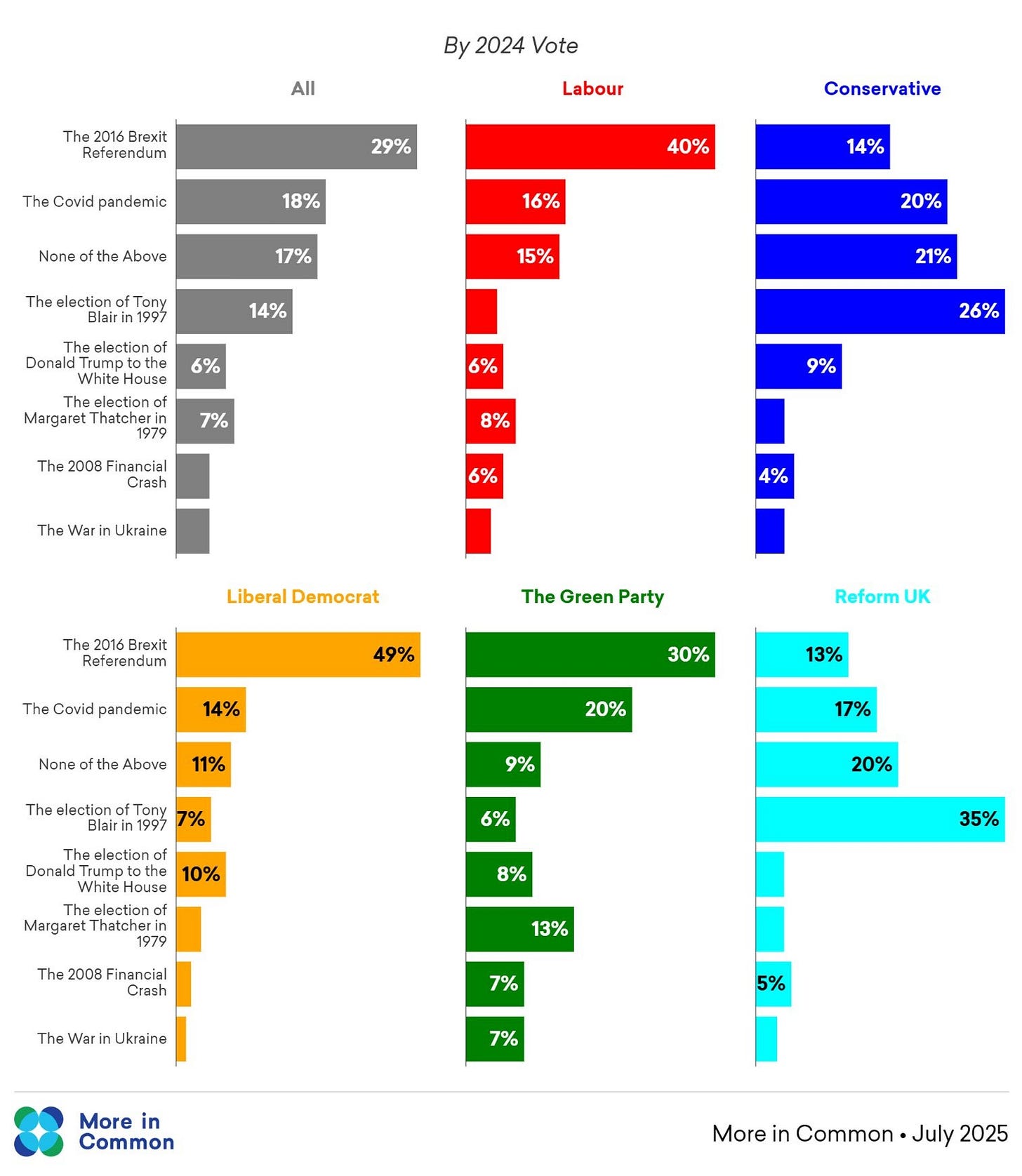

This story begins, as so many classics do, with a neat bit of polling by More in Common. Of respondents who said that Britain was on the wrong track, it then asked them which moment was most responsible. The options were, in chronological order, as follows:

The election of Margaret Thatcher in 1979

The election of Tony Blair in 1997

The 2008 financial crash

The 2016 Brexit referendum

The Covid-19 pandemic

The war in Ukraine

Or none of the above

As you can see, the EU referendum came out the clear winner overall, as well as for each voter group except Conservative and Reform UK. Which means that, once again, the British public is wrong. The correct answer is, of course, the 2008 financial crisis, from which so much of our contemporary world was forged. (Though I would have liked to have seen a 2010 coalition government option, which I suspect would have eaten into Brexit’s numbers.)

Obviously, one could always take an additional step back in time and conclude that that was the key decision or moment. For instance, what if James Callaghan had gone to the country in the autumn of 1978? What if Lord Halifax had succeeded Neville Chamberlain in May 1940 and sued for peace? What if Richard III had won at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485?

Still, it’s 2008 for me, Clive. The financial crash sparked, exacerbated or paved the way for pretty much every subsequent crisis. In party political terms, it precipitated the end of New Labour and the rise of the Cameron/Osborne axis. In economic terms, it drove a vast rise in borrowing and stopped productivity growth in its tracks. And in cultural terms, it fuelled sustained anger at politicians, mistrust in institutions and the rise of conspiracy theories.

But there is one specific consequence of the financial crisis and great recession I think flies under the radar: the sharp rise in asset prices, specifically housing, propelled by the era of cheap money. Between February 2009 and May 2022, UK interest rates did not exceed 1%. Indeed, for most of the period, they were 0.5% or less. This represented a historical absurdity, and the results were always going to be messy.

A health warning: the housing market is, like any market, impacted by both supply and demand. And clearly there has been far too little of the former, particularly given record levels of net migration in recent years. At the same time, governments in trouble have invariably sought to juice up demand, whether by supporting first-time buyers or through stamp duty holidays.

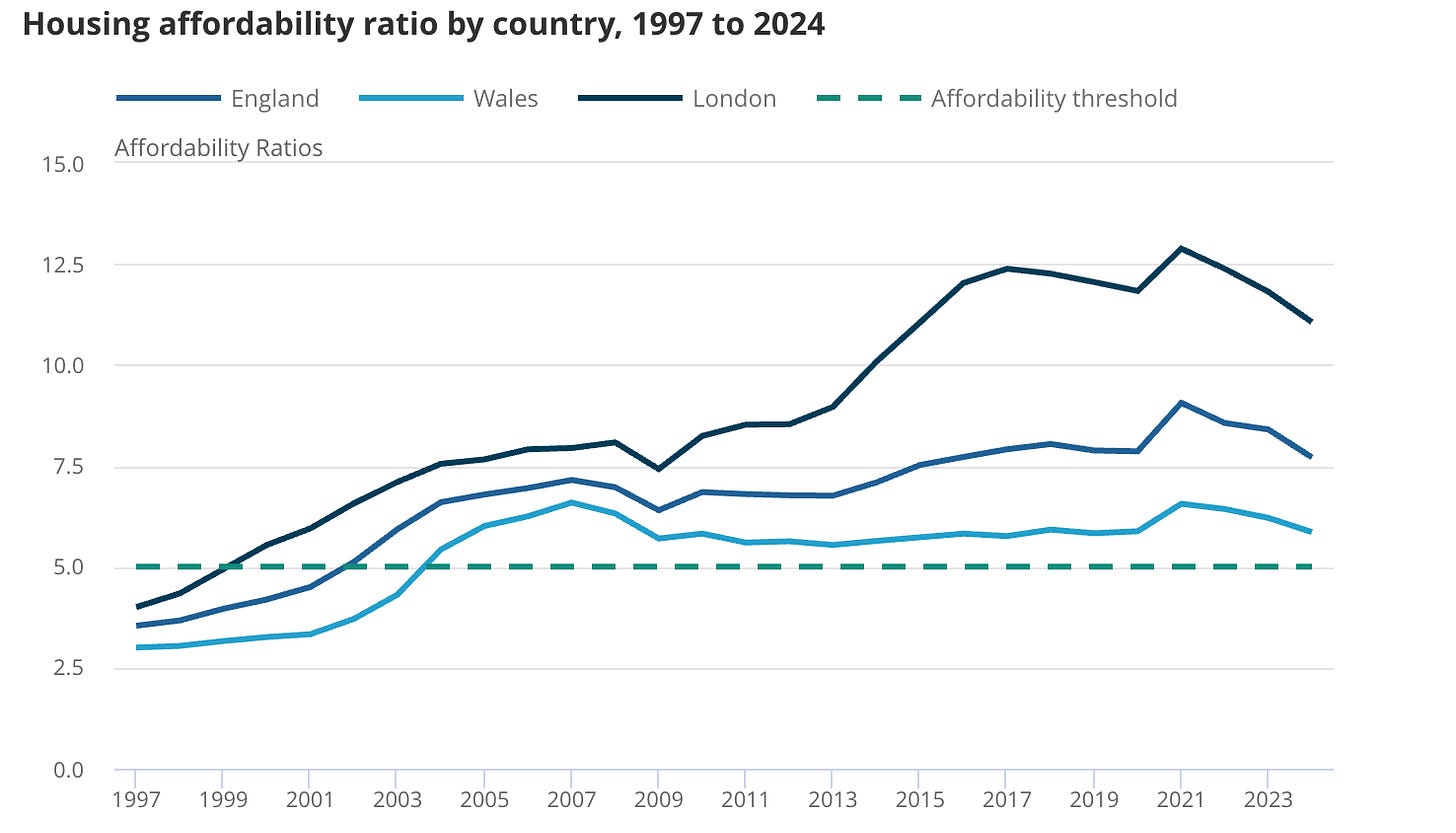

Nevertheless, the cost of housing is largely determined by the cost of money. It is not simply a home, but an asset class much like commodities or equities. And they are highly responsive to interest rates. To that end, a 2019 Bank of England working paper found that “the rise in house prices relative to incomes between 1985 and 2018 can be more than accounted for by the substantial decline in the real risk‑free interest”.

And rates were never lower than in the 2010s. The result? In 2021, house prices in England hit a modern-day record 9.06 times average earnings, according to the Office for National Statistics. As interest rates rose from late 2022 to combat post-Covid inflation, housing markets began to deflate and that figure has fallen back to 7.7 times median average earnings.

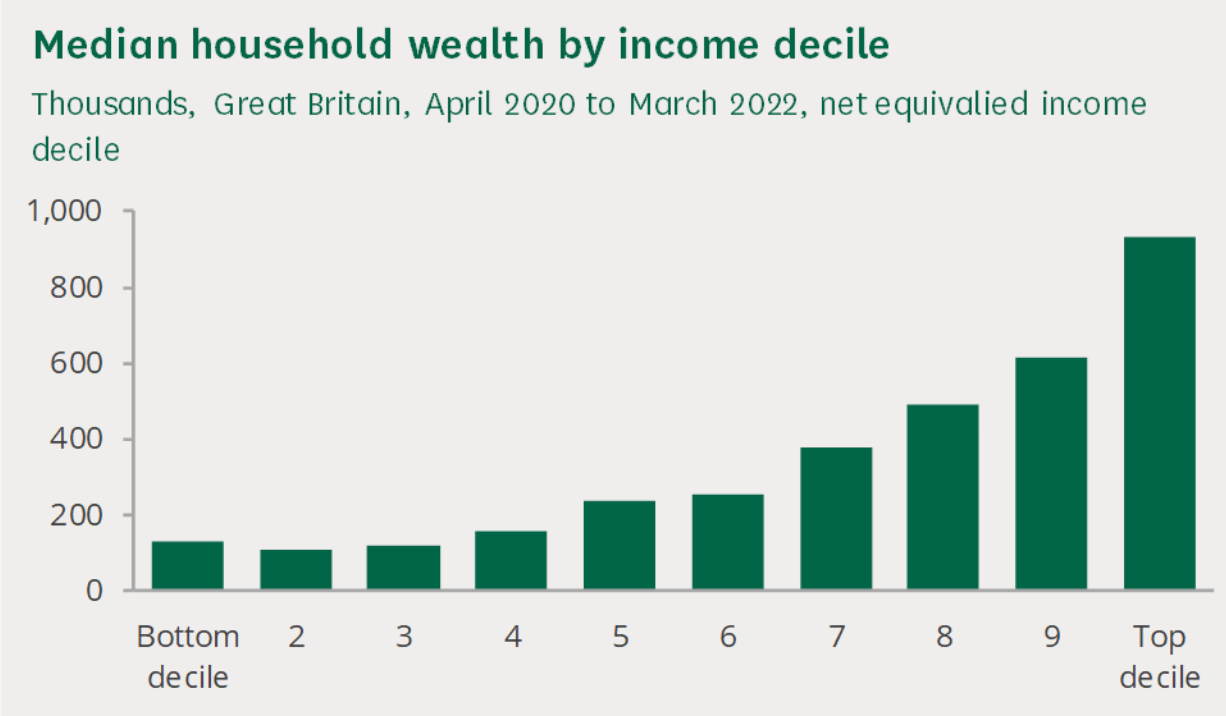

Of course, housing was not alone. The era of cheap money sucked vast amounts of capital into technology companies, some of which bore fruit (electric vehicles) and some which did not (the Metaverse). But either way, it was a good time to be an investor. The stock market went on a tear, as ultra-low rates incentivised companies to boost returns, often through share buybacks, mergers and leveraged buyouts. All this inevitably has an impact on inequality.

Consider the Gini coefficient, a measure of inequality, where a figure of 0 indicates perfect equality (everyone has the same) and 1 indicates perfect inequality (one person holds everything). Income inequality in Britain has remained relatively stable since 1990, at around 0.35. But wealth inequality has widened dramatically, and now sits at around 0.59.

From April 2020 to March 2022, the wealthiest 10% of households had wealth of £1,200,500 or more, while the least wealthy 10% had £16,500 or less, according to the House of Commons Library. Absent policy change, these levels are likely to persist, as the baby boomer generation dies and passes on their houses and other investments to their children.

Whether or not Labour achieves its target of building 1.5 million homes over the parliament, the greatest impact on house prices (and wider inequality) will remain the cost of money. Interest rates may not be falling as fast as the chancellor would like, but the direction of travel is clear.

In my view, the greatest risk to social cohesion and economic stability is not a house price correction, but a growing and possibly permanent schism between owners and renters. A property market that experiences undulations like any other, but where millions of people are essentially unaffected — either because they have built up so much equity over the years, or they are stuck in short-term and sometimes unsafe accommodation, their chances of buying a home drifting ever further into the distance.

It is not all the financial crisis’ fault, of course. But nor do we seem to have recognised the conundrum, let alone identified a satisfactory policy response.

Thanks for this article that summarises nicely a major driver of inequality in the UK (and elsewhere).

But let’s not forget that it was the deregulation initiated by Margaret Thatcher, and continued by Tony Blair’s New Labour, that allowed the financial crisis to happen.

Not to mention the steady reduction in the number of the council houses.

Jack,

You are obviously an ex Treasury man by your obfuscation by detail !