Can't we talk about something else?

The dangers of both ignoring — and obsessing over — immigration

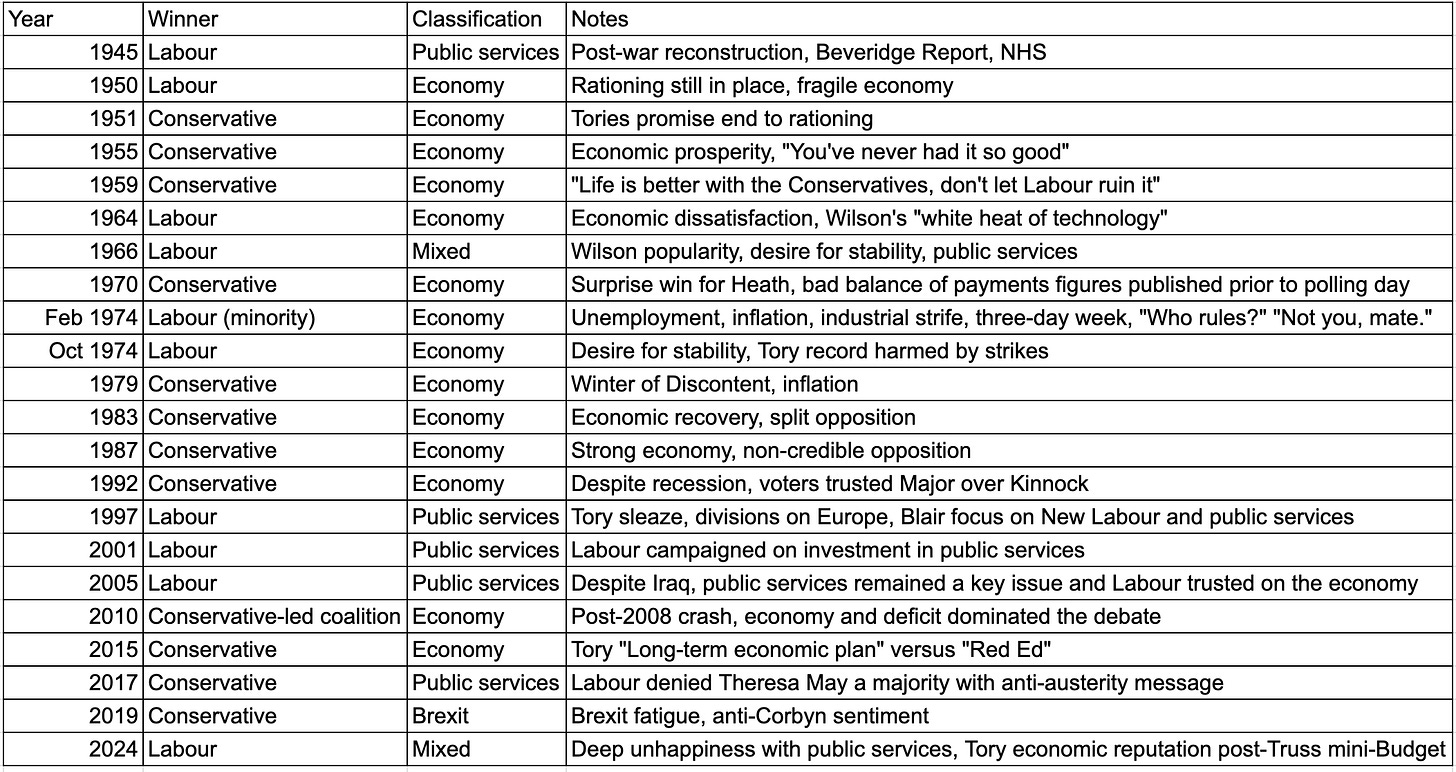

British elections tend to hinge on which issue voters care about most. When the primary concern has been the economy, the Conservative Party often prevails. When the state of public services is front of mind, Labour has stood a better chance.

This trend partly reflects enduring public perceptions: the Conservatives are viewed — rightly or wrongly — as the party of economic competence, low taxation and fiscal restraint. In short, mean but reliable. Labour, by contrast, defines itself through a commitment to the NHS, education and vague notions of equality. Kind-hearted, but also a bit useless.

This is, of course, not a hard and fast rule. No such things exist in politics. For instance, by the eve of the 2005 election, such was Labour’s confidence in its economic record that Tony Blair was warning a vote for the Conservatives meant, “Economic stability is at risk, your job is at risk, your mortgage is at risk, the economy is at risk.”

With that disclaimer out of the way, here’s a quick and dirty summary of elections since 1945:

The one that sticks out in my mind is 2017. It is difficult to imagine it now, but for a time, Theresa May bestrode British politics. Her first PMQs performance was considered a triumph. Her joint chiefs of staff, Fiona Hill and Nick Timothy, struck fear into junior ministers and senior civil servants alike. “Brexit means Brexit” was treated by some commentators as if it carried the strategic weight of George Kennan’s Long Telegram. As we know, that all changed following the snap election, in which the Tories lost their majority.

May had intended for the 2017 election to be a Brexit election. Unfortunately for her, the British public decided otherwise. Disenchantment with austerity and the state of public services dominated the campaign. So much so that the Manchester Arena bombing — in which 22 people were killed and more than 1,000 injured — became less a debate about Jeremy Corbyn’s perceived weakness on national security, and more about cuts to police numbers.

Don’t talk about immigration

There is a third issue that tends to befuddle both Labour and the Tories: immigration. Keir Starmer would prefer if it simply went away as an issue. He would much rather take on Reform UK in areas where his party is stronger, ideally the NHS. Many on the liberal Left feel the same way. They point out — not without reason — that it is impossible to outflank the populist/far/hard [delete as applicable] Right on immigration. And that doing so only makes it a bigger issue.

I should know because, back in May, I suggested that Starmer risked turning voters on and sending them off to Farage. Specifically, that the prime minister had “chosen to raise the salience of immigration” without reducing it to “the sort of numbers that might satisfy its loudest opponents.” I don’t resile from that view. But the trouble with completely ignoring immigration as an issue is that it doesn’t work either.

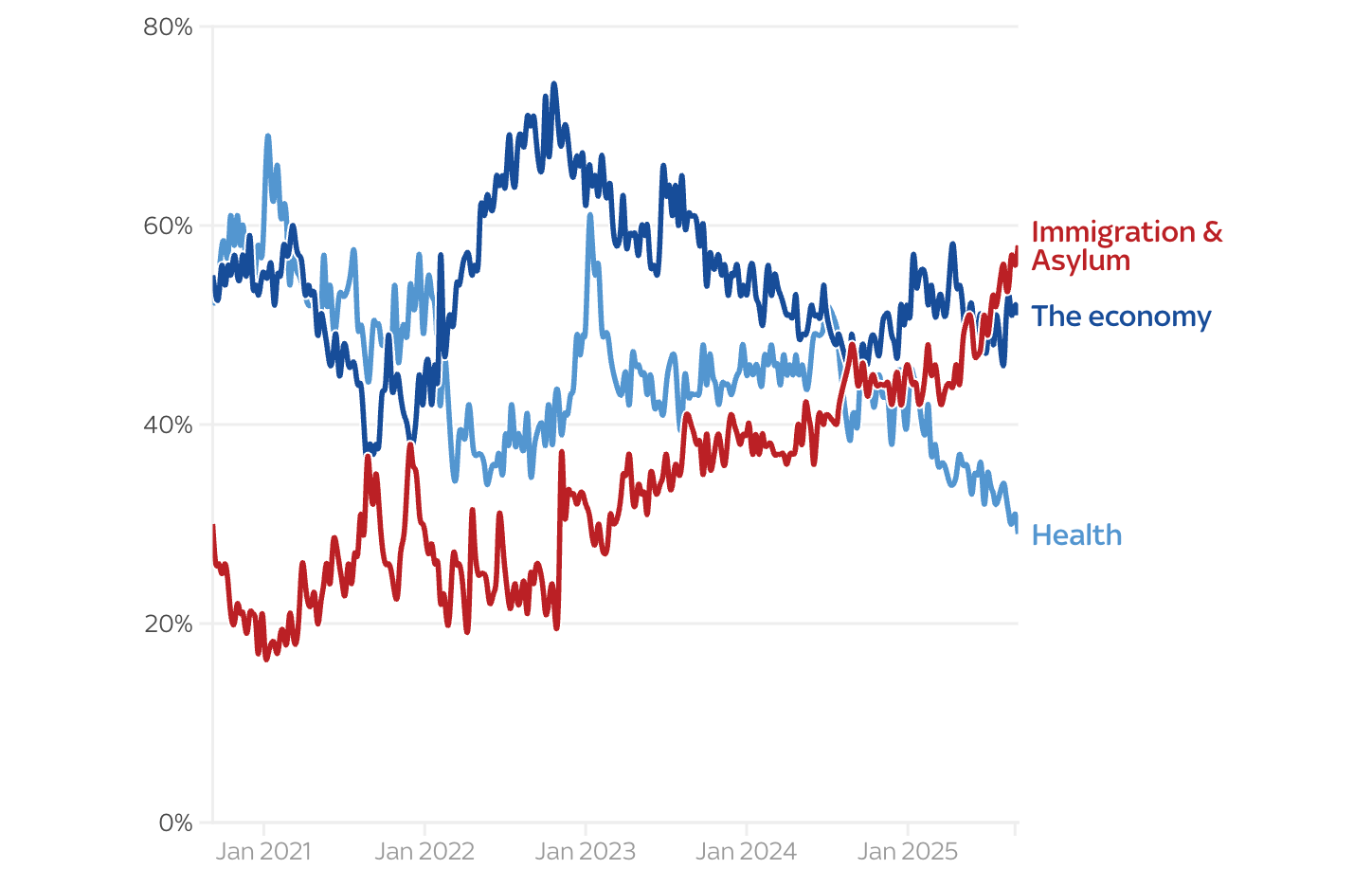

For the first time since the referendum, immigration and asylum is the top issue of public concern, according to a recent YouGov survey for Sky News. I simply do not think that leaving the field open to Nigel Farage and Reform UK will end well either for the government or many hundreds of thousands of people living legally in Britain. In fact, we have a pretty decent case study to suggest doing so is a losing bet.

During the 2016 EU referendum, immigration was a central theme of the Leave campaign, perhaps most famously distilled by the so-called ‘Breaking Point’ poster released during the final week by Nigel Farage, which depicted a photograph of Syrian refugees at the Croatia-Slovenia border. I also hold a special torch for Penny Mordaunt, who suggested — falsely — that Turkey was poised to join the EU and that as a member state at the time, the UK would not have been able to block it.

But the Remain campaign, led in large part by David Cameron and George Osborne, calculated that focusing on immigration would only draw more attention to an issue on which they were politically vulnerable. So they focused instead on economic risks of leaving the EU. This had a ring of cold political logic to it.

Since the free movement of people is a core EU principle, the Remain side couldn’t credibly promise to reduce immigration. But nor did they do much to defend immigration, or explain its benefits in terms of the economy and public services. Consequently, Leave owned the narrative — and in particular — that tantalising and emotive message: “Take Back Control”.

In recent days, the new Home Secretary, Shabana Mahmood, has attempted something of a third way on immigration. She told staff:

“We can only be a tolerant, open, generous country when we are able to determine who can enter and who must leave. And I know that a country that can control its own borders is a far safer country for someone who looks like me.”

If it weren’t already obvious, I have no answers. But this much seems clear: governments that ignore high-salience issues lose. Governments that raise their salience but fail to act also lose. The only path left is the hardest one — to govern well, and to be seen to govern well. Everything else is noise.

Is not a part of the answer your statement "But nor did they do much to defend immigration, or explain its benefits in terms of the economy and public services"?

One could add cultural enrichment, the sheer wrongness of judging people by skin colour, and in the case of asylum seekers the duty to help the suffering (for the Christian nationalists one could call it a Christian duty).

For EU freedom of movement and the possible UK/EU youth mobility scheme people should be reminded that migration works in both directions. Brexit was after all a huge loss of rights for British citizens.

There is also the question why in a rich country with a decent education system the anti-immigration lobby wishes the bad jobs to be done by Britons rather than poorly-educated foreigners for whom they would be a step up. And given an ageing society what is the trade-off from lower immigration for pensions, taxes and retirement age?

Starmer's "Island of Strangers" comment supported Reform's line. It was also dangerous for anyone in this country with foreign looks or name, even if British. Kemi Badenoch's complaints about receiving racist slurs should lead her to think about her party which is doing so much to stoke nationalism which in many people's minds means white nationalism.

But a sustained defence of immigration and anti-racism from the government and other parties that goes beyond the Home Secretary's luke-warm reasoning which you report might help peel some support from Reform. At least it would raise the tone of the debate.

The problem of the small boats full of illegal immigrants could be solved by direct intervention. Currently our brave, indefatigable Border Force meet these frail craft and take on board all the occupants, presumably including the man on the tiller who must be part of the gang who run the system, charging each traveler over £1000 for the trip. There is experience of a similar operation out of Vietnam after the communist takeover in 1975. Many people simply took to boats and relied on ships to rescue them at sea. However, some of the “Boat People “ were also plagued by pirates who kidnapped their women and killed the men. The problem was only solved by the refugees being incarcerated, mainly in Hong Kong, until they agreed to return to Vietnam. In the English Channel, divided between Britain and France the illegal immigrant boats could be boarded by SAS type British soldiers, from Border Force boat, armed and in pairs, who would take control of the vessel and sail it back to France. The boarding would have to be in British waters so that no French laws were violated. Once in shallow waters off the coast of France the occupants of the boat would be disembarked and the vessel sailed back towards the Border Force ship which the two soldiers would join and tow the captured vessel back to Britain for disposal. I appreciate many would object to this suggestion but this problem must be solved and no one else, including you, Jack, seem to have any suggestions. I used to do the “booze cruise “ before it was stopped. We had to examine our vehicles anytime after we had parked them to have lunch or for any other reason. The Customs Officers on the Ferry also examined our vehicles to prevent illegal immigration. Drastic action is required and if not implemented Farage may be our next Prime Minister.