Is Keir Starmer still good at this?

His methods got him selected to a safe seat and elected Labour leader. What if they no longer work?

Prime ministers would be wise not to read the newspapers. John Major reportedly stayed up late into the night, nervously awaiting the first editions. The habit served only to consume vast amounts of energy and scarcely led to better coverage. Years later, he would admit to being “much too sensitive” about what the press wrote.

Even the back pages do not always provide much sanctuary. If Arsenal fan Keir Starmer read the sports pages this weekend, he would have seen that Graham Potter was sacked by West Ham after a fairly calamitous nine months in charge, in which the club won just six of 23 Premier League games. This represents a second successive managerial failure, after lasting 31 matches in charge of Chelsea.

It’s all a bit confusing. This is the same Potter who shot to fame managing unfancied Swedish side Östersund, before going on to have great success in the Premier League with Brighton, where he guided the club to what was then its highest top-flight finish. There was a reason why Chelsea hired him, and why they were prepared to pay £16m for the privilege.

I wonder if Starmer saw any similarities in this trajectory?

Keir Starmer was good at politics

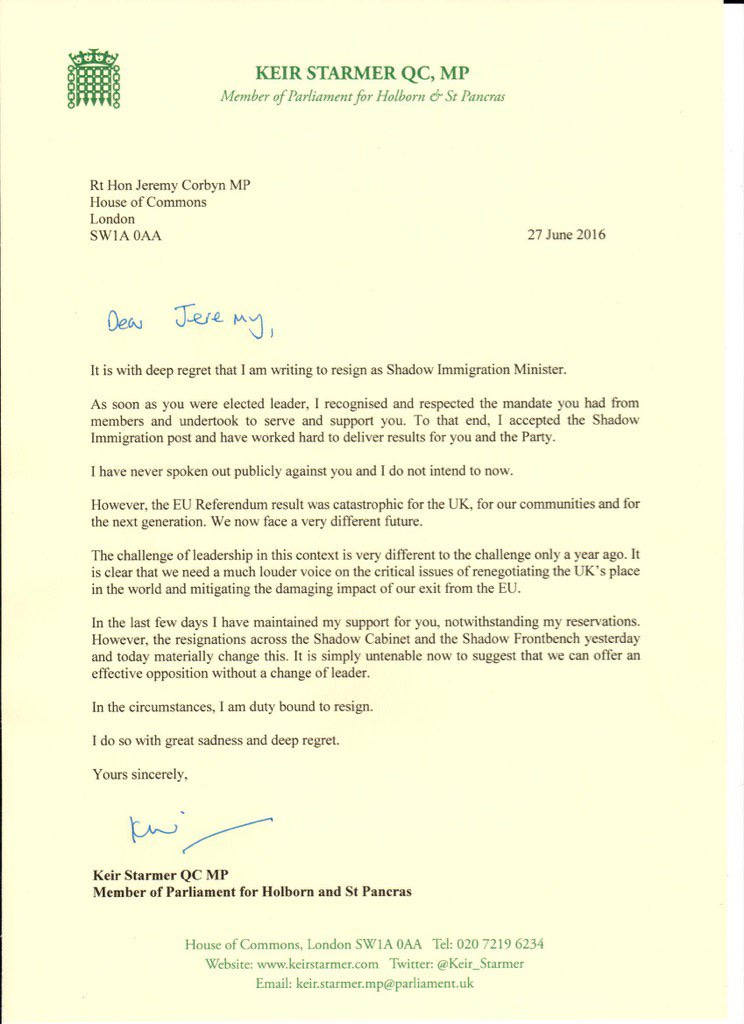

It is demonstrably false to assert that Starmer lacks political judgement. As a new MP, he identified that the next Labour leader would have to come from within Jeremy Corbyn’s shadow cabinet. And so — even though Starmer did resign as a shadow minister as part of the mass resignations following the EU referendum — it was one of those ‘in sorrow rather than anger’ letters.

After Corbyn secured re-election as Labour leader, Starmer swiftly accepted the post of shadow Brexit Secretary, a position he wielded for maximum political benefit. By serving in the shadow cabinet, Starmer could not only demonstrate loyalty to the leader, but he could also leverage the sharpest dividing line between Corbyn and the membership: Europe.

Labour members at this time loved their leader, but unlike him, they also largely wanted to stay in the EU. Starmer sensed an opening. He used his role (those in the leader’s office may say “abused”) in order to shift the party’s position towards a second referendum. This was the political sweet spot for anyone hoping to succeed Corbyn. Public fealty to the leader, but firm pro-EU credentials. It worked.

Starmer went on to defeat the actual Corbynite candidate, Rebecca Long-Bailey, to win the 2020 Labour leadership election, with 56.2% of the vote in the first round. And having secured the position, he subsequently went on to denounce Corbynism, attempt to rid the party of antisemitism and even kicked his predecessor out of the party with such élan it would have made Nikita Khrushchev blush.

This was not even the first time Starmer had demonstrated strategic patience in advancing his political career. Having stepped down as Director of Public Prosecutions in November 2013, Starmer stood for the safe Labour seat of Holborn and St Pancras — with a little help from party HQ.

It was reported at the time that rivals complained that the contest was delayed by then leader Ed Miliband to ensure that the former DPP had been a member of the party for the necessary 12 months in order to stand.

And so what

Potter has not become a bad manager overnight. His skills worked at Östersund and Brighton because these were two clubs who built a system and then went out to find the person most suited to it. That wasn’t the case at either Chelsea or West Ham, the latter of which simply lacked the kind of footballers to play the style he wanted.

Similarly, Starmer has not suddenly transformed into a bad politician. His antennae got him selected for a safe seat, elected Labour leader after only five years in the Commons and then prime minister with a massive parliamentary majority. But what got him there no longer seems to be working, as the economy stagnates and the party haemorrhages support on both its Left and Right flanks.

Journalese practice demands that I wonder out loud whether Labour needs to give it to ‘Big Andy Burnham’ until the end of the season. Readers will know my scepticism (who is giving up their seat, exactly?). But questions remain.

Starmer, unlike Potter, has not moved clubs. But running a coherent government is a different ballgame to corralling an opposition — just as the pressures of managing Chelsea bear little relation to that of Brighton. What worked then may not work now.

Housekeeping: Huge thanks to everyone who filled out the questionnaire last week — I really appreciate it. Your feedback’s already helping shape where this newsletter goes next.

Nice piece, Jack.

If Starmer is Potter, who are Polanski and Farage?

If only running the country was as simple as winning the Premier League title. As one critic said about the House of Commons, it is the Opposition that is in front of you, it is your critics and back stabbers who are behind you. It is said of Starmer that he would not listen to his Chief Whip on his attempt to reduce PIP payments to people on benefits. He has nearly four years to regain his composure and start gaining popularity with his MPs and supporters, of whom I am one. However we will know within a year, as we knew with Gordon Brown, whether he can win the next election or not. He should be as astute as the rest of us by then and know if it is time to step down.