It's not *all* Rachel Reeves' fault

Concerns over debt and geopolitical instability mean governments around the world are having to pay more to borrow

After “life’s not fair” and “let it go, Jack”, my parents seemed to revel in observing that “the world doesn’t revolve around you.” And from a celestial mechanics perspective, they were surely right. The Earth revolves around the Sun every 365 days, the Sun revolves around the Milky Way’s galactic centre every 225–250 million years, and the Milky Way… Well, it doesn’t technically revolve around a single point, but it is on a trajectory to collide with the Andromeda galaxy in around 4–5 billion years. (If not already abundantly clear, raising me was not always a straightforward endeavour.)

Of course, all children (and plenty of grown-ups too, for that matter) suffer from varying degrees of main character syndrome. This isn’t a moral failure. A combination of cognitive development, limited life experience and an element of natural egocentrism mean that young people often struggle to imagine a world in which they are not the centre of attention. Sometimes, entire economies are guilty of it.

T-bills, T-bills, T-bills

A few weeks ago, there was a flurry of excitement as UK borrowing costs hit their highest levels since 1998. There were, to be fair, some UK-specific causes for the spike. The markets are increasingly concerned about Britain’s high debt, anaemic economic growth and stubborn inflation, which remains almost twice the rate in the eurozone. Investors also have questions about the Labour government’s capacity for fiscal discipline, following the U-turn on welfare changes.

But this jump in long-dated bonds is taking place around the world, from the United States to Europe, Japan and beyond. Earlier this month, yields on 30-year US Treasurys approached 5%, Japan’s 30-year bond yields hit a record high, French 30-year bond yields hit levels not seen since the 2011 eurozone crisis. Even goody-two-shoes Australia, with a debt-to-GDP ratio of just 37%, faces having to pay more to finance its debt.

The reality is that long-dated bonds are facing sell-offs for many of the same reasons: concerns over government spending, persistent inflation, weak growth and political instability. And whatever your view on Rachel Reeves’s performance in the Treasury, she is not responsible for every country’s woes.

Can I borrow a trillion?

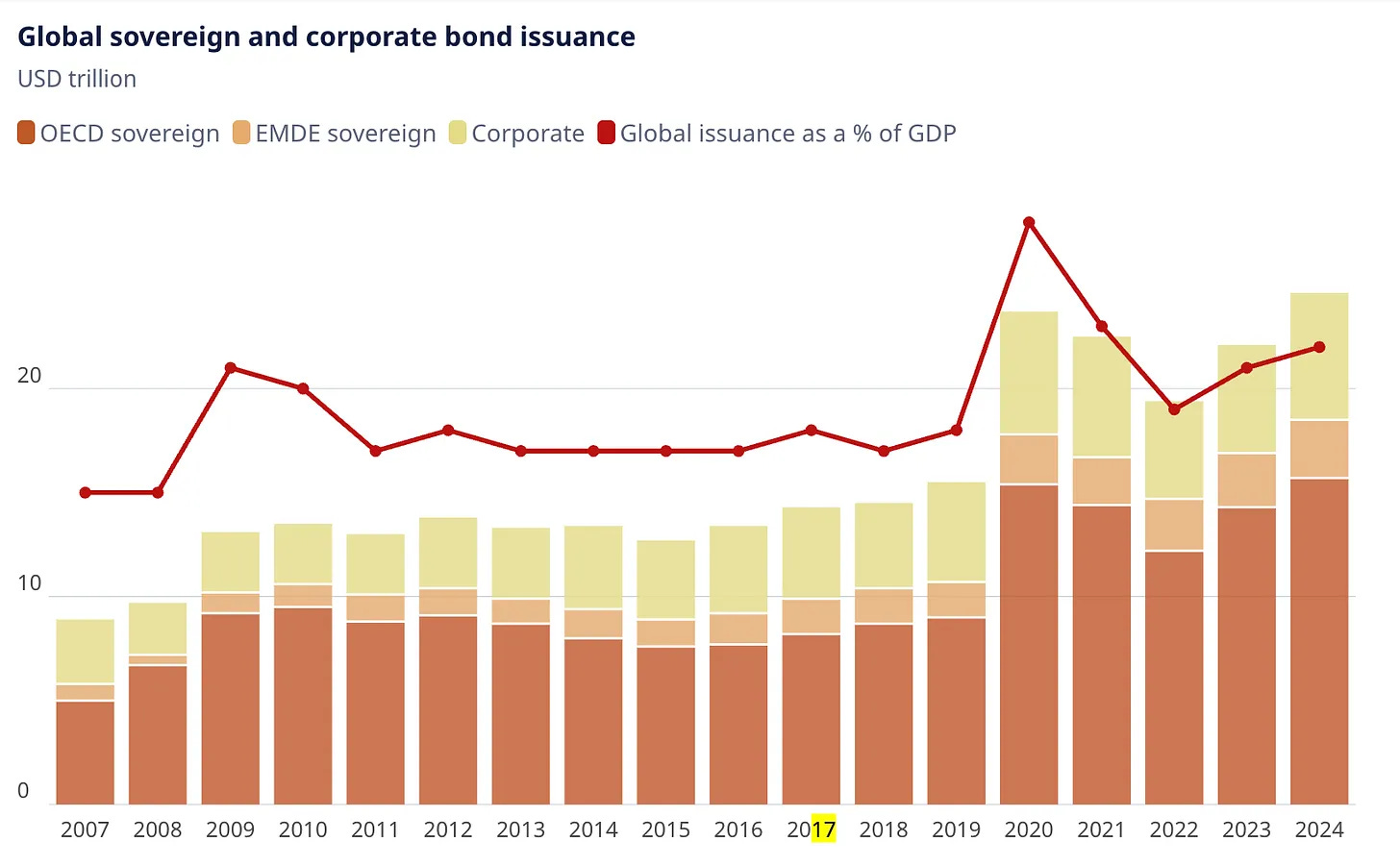

Global debt has been on a rising trajectory this century. Governments borrowed heavily (and cheaply) in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, and then again to combat the Covid-19 pandemic. Throw in the costs of an ageing society, the energy transition and rising defence spending — and the pressure on public finances becomes even more intense. Little wonder that a recent OECD report on government debt estimated that issuances by member states would rise to $17 trillion this year, up from $14 trillion in 2023.

As alluded to above, politics is a major part of this. Donald Trump’s tariffs have thrown sand in the gears of the global economy. His threats to Federal Reserve independence have spooked the markets. A rotating cast list of French prime ministers, Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine and continued US-China tensions mean that investors are demanding higher yields.

Not least when they have options for where to put their money. Companies, like nations, need to borrow, and they are doing rather a lot of it. Global corporate debt sales hit a record $8 trillion last year, amid higher demand and lower borrowing costs. These often generate higher returns, as corporations are deemed more likely to go bust than nation states. But not always.

Take France, which is grappling with a rolling political crisis and rising concerns about its sovereign debt. The Financial Times reported this week that yields on bonds from firms such as L’Oréal and Airbus have fallen below that of French government debt. In other words, investors view lending to some private companies as less risky than to the French government.

Then there is quantitative tightening. Central banks, including the Bank of England, have been quietly selling off some of the debt they amassed via quantitative easing over the last 20 or so years, which is having an upward impact on yields. (For more on this, check out this excellent and highly readable piece by Sky News’ Ed Conway.)

At the Budget in November, the chancellor faces real and growing pressure to demonstrate that the UK’s fiscal trajectory is a sustainable one. Given the deluge of underwhelming economic indicators and whispers about Office for Budget Responsibility productivity forecasts, that is no easy task. But not every bond yield spike is a judgement on the UK economy alone. And not every downgrade is Reeves’ fault.

Still, looking at some of the options available to the chancellor, that collision with the Andromeda galaxy can’t come soon enough.

Wishing every reader who celebrates a happy, healthy and peaceful new year

Thank you for the link to the Sky analysis. I studied economics in 1961 but Bonds yields and QE were not on the syllabus. Don’t worry about the crash of the galaxy in 4 billion years as our Sun will have burned out by then and we will have moved to another planet. How complex it is. Neil Kinnock is the first politician to advocate an application to rejoin the EU while multi-millionaire Dyson tells us it is worth being poorer outside the EU because of all the additional freedoms we have. One of those freedoms is the right to owe the energy companies over £4 billion in unpaid energy bills.

Shana Tova