It's not just a Starmer problem

A more charismatic Labour leader would face the same economic constraints and political trade-offs

From the early hours of 24 June 2016 until 11pm on 31 January 2020, Brexit was fundamentally a political problem. The uncertainty over the UK’s future relationship with the EU certainly acted as a drag on growth and investment, but that was secondary to the arm-twisting, endless ministerial statements and general histrionics taking place in parliament.

As a result of this political volatility, the Conservative Party cycled through a number of leaders. David Cameron had little choice but to resign following the referendum, given that he had campaigned vigorously for Remain and could not therefore act as a credible negotiator of Brexit.

His successor, Theresa May, famously tried, tried and tried again to pass her Brexit deal, but failed in fairly spectacular ways. She, too, had to go, a decision that was vindicated when Boris Johnson secured a substantial parliamentary majority before successfully negotiating a hard Brexit and terribly thin trade deal with the EU.

The UK did not experience a constitutional crisis, or even a constitutional nuisance. But it was a political crisis, and one that was ultimately solved by politics. This is, it seems to me, in stark contrast with the issues facing today’s Labour government. And therefore one where changing the leader would make little difference to the problem at hand.

To be clear, it is not that no one could do a better job than Keir Starmer. The prime minister lacks charisma and struggles to connect emotionally with voters. His theory of party management suggests he views backbench MPs as cogs in a vast bureaucracy, rather than as stakeholders with agency. He has subcontracted economic policy to his chancellor, whose promises on taxation severely limit fiscal room for manoeuvre. To top it off, the general lack of direction from Number 10 means that ministers often do not know what their leader wants.

Yet, it is not obvious what the Platonic ideal of a Labour leader — let alone Andy Burnham — could do better. And that is because the central constraint faced by this government is economic, not political. In the last week alone, it has emerged that the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) is set to downgrade its estimates for productivity growth, which could open up a fiscal black hole worth tens of billions of pounds.

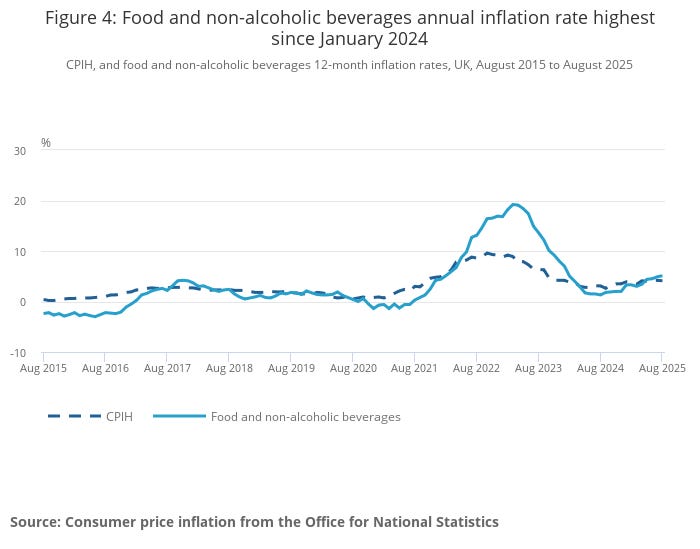

Then came yesterday’s inflation figures from the Office for National Statistics, which showed the figure holding steady at 3.8%, driven in large part by a 5.1% rise in food costs — the fastest jump since the start of last year. The Bank of England has forecast that inflation will peak at 4% this autumn, which is double the 2% target as well as almost twice the rate in the eurozone.

This is bad news for consumers (have you seen the price of butter?!) but also for government borrowing, as stubborn inflation will slow the pace of interest rate reductions. Of course, things might not be so bad if inflation were accompanied by strong growth and a buoyant jobs market. Would that it were so simple.

The UK economy expanded by an anaemic 0.3% between April and June, after growing by 0.7% in the first quarter, weighed down by higher taxes and US tariffs. As for the labour market, the Financial Times reported earlier this month that British businesses were cutting jobs at the sharpest rate for four years and forecast the weakest employment outlook since the Covid-19 pandemic, blaming the rise in national insurance contributions.

No government is powerless. Labour has elected to stick to a series of red lines that limit its options, such as in getting as close to the EU without joining the single market and customs union, ruling out raising taxes on ‘working people’ and leaving so little fiscal headroom that the chancellor is constantly at the mercy of even minor changes to OBR forecasts.

Still, I suppose my question is: what would another Labour leader do differently, within the bounds of fiscal reality? The scope to borrow more for day-to-day spending simply does not exist. Recall that the markets went haywire back in July not because Rachel Reeves cried, but because they feared she might be replaced by a new chancellor who would loosen the fiscal rules.

Those whose only policy proposal is to call for a wealth tax seem not to understand that the government has already raised quite a lot from the well-off and plans to come back for more at the Budget in November. Indeed, I wanted to write a piece on Monday about how you don’t need a wealth tax to tax wealth, but Dan Neidle got there before me and did it better anyway.

Look, I get it. Governing Britain in an era of high inflation and low growth is a frankly miserable experience. Labour backbenchers and members would no doubt feel better about life if they woke up to find Andy Burnham or Angela Rayner in charge. But then they would have to get out of bed, draw the curtains and realise that being a decent northern bloke or lass does not, in fact, alter fiscal reality.

Housekeeping: I’d love your feedback. This short, anonymous survey (one minute) will help me improve Lines To Take and shape what comes next. Whether you read every issue or just now and then — your thoughts really matter.

A nice summary of tax options in the FT. Whatever next. I believe we will eventually tax what is called wealth. Much of it is in land which has not changed hands since before the Land Registry was formed and is therefore outside the system. The abolition of Stamp Duty in the FT article hinted that land value should be taxed instead. Extend such a tax to the people who own most of the land in the UK and you have a wealth tax. I disagree with most of your opinions on Brexit which was a Tory shitshow. Cameron was blackmailed by Jacob Rees-Mogg and the 70 members of the ERG into promising a referendum if he got a majority in 2015, which he did. This was a major institutional question that should have required a 67% majority. Not only was that not included in the requirement, the Ex-Pats who lived in Europe and were allowed to vote in General Elections were excluded as they had an interest in remaining in the EU. Cameron could have declared that the majority was too small to justify leaving the EU but lacking the courage to do that, he resigned. His successors were the blind leading the blind.

David Cameron behaved dreadfully and irresponsibly. He was weak and clearly lacking in good judgement. To hold a referendum - effectively on his leadership - mid term, when tradition dictates that the ruling party is at its least popular was insane. The mood of the country had already been hinted at, in the poll for naming a good, sensible survey ship. The ridiculous choice of a tired, worn-out formula for the monica of this marvellous new vessel was an indication of the cheeky rebellious mood of the people. And surely Rowen Atkinson himself must have raised his eyes to the heavens.

Back to Cameron then; having reaped the rewards of his utter foolishness, he then split and ran. What a disgrace! He could have at least tried to style it out, to say to the nation “ok, I get it. That’s a surprise. I need to listen to you a bit more…”

But no. The cringing creep upped and legged it, leaving chaos in his oily wake.

Productivity won’t be improved by government tinkering. It’s the mood of the country that needs to be lifted. Only then will people pick up their shovels with greater determination to look back on a day of work well done.