Morgan who?

It shouldn't matter this much who the prime minister's chief of staff is

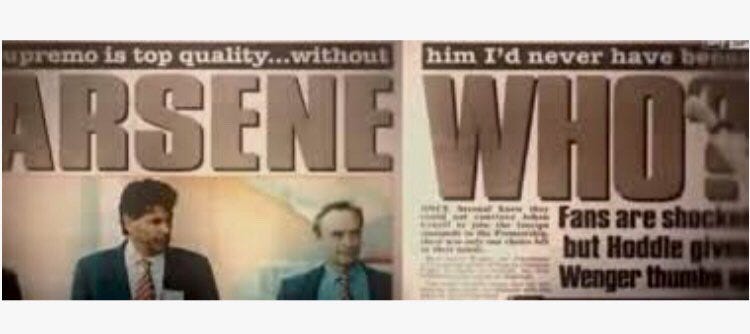

It’s all a bit Spursy1, isn’t it? North London’s second team recruited an up-and-coming coach and promptly reduced him to type. Having led unfashionable Brentford to multiple top-10 Premier League finishes, now Tottenham manager Thomas Frank is the bookies’ favourite to be sacked, with Spurs just six points clear of the relegation zone. Meanwhile, his former side sits seventh in the table.

Certainly, credit is due to Frank’s replacement, Keith Andrews. But the reality is that Brentford is a fundamentally well-run club. And while it would be reductive to suggest that anyone could do the job, the organisation’s system, culture and recruitment model are so strong that its fortunes simply do not hinge on a single manager.

And sure, the English Premier League and British politics are not the same. For one thing, the former is a wildly successful and highly lucrative export while the latter lurches from one crisis to the next. Governing is also, bluntly, a lot harder. A football manager can simply sell an uncooperative player, but when Keir Starmer sacks Lucy Powell from his cabinet, she hangs around on the backbenches — and even gets herself elected deputy leader.

Nevertheless, in both sport and politics, having a clear direction set from the very top matters a great deal.

Captain Morgan

On Sunday, Morgan McSweeney resigned as the prime minister’s chief of staff. In a statement, he said:

The decision to appoint Peter Mandelson was wrong. He has damaged our party, our country and trust in politics itself. When asked, I advised the prime minister to make that appointment and I take full responsibility for that advice.

In the short-term (what else does Starmer have at this point?), this represents a body blow to a weakened and isolated prime minister. But his exit further highlights the sheer dysfunctionality of this Downing Street operation.

The issue here is not that oft-repeated maxim, whereby when the advisor becomes the story, it’s time for them to go. Instead, it is that it really should not matter quite this much who the prime minister’s chief of staff is, beyond the usual questions of competence and judgement. That is because the appointment of senior advisors should be downstream from the core strategy — not the other way around.

Alistair Campbell, former director of communications for Tony Blair, is the textbook example. Campbell left his post in August 2003, in large part because it was felt he had become a lightning rod for controversy over his role relating to the Iraq War and the Hutton inquiry. See this electric appearance on Channel 4 News in June 2003, replete with a somewhat startled Jon Snow.

Campbell’s exit was no doubt a blow to the Blair government, because he was exceptionally good at his job. But the departure did not — and was never going to — fundamentally alter the direction of that government or the New Labour project. And the reason for this is because that direction was set by Blair himself.

Theresa Maybe

Contrast this with Theresa May. Shorn of her joint chiefs-of-staff, Fiona Hill and Nick Timothy, following the disastrous 2017 general election, May’s government shifted dramatically. Some of this can be attributed to the loss of a parliamentary majority and therefore political power. But it is also simply true to say that — beyond cutting immigration and opposing modern slavery — May did not have a clear political project. Indeed, her last-minute 2050 Net Zero pledge looked suspiciously like a Hail Mary for a legacy.

And so we return to Starmer. This is, recall, a prime minister who gave a speech warning about the dangers of Britain becoming “an island of strangers” one day, before launching into something of a full-throated defence of diversity and multiculturalism at the next Labour Party conference. Of course, all prime ministers are capable of making errors, even bad ones. But this sort of thing does not happen if the principal has a clear direction in which he wants to take the country.

Like a new signing

All this is to say that, without McSweeney, Number 10 may pivot from chasing Reform UK votes to trying to win over those on the left-of-centre more likely to actually consider supporting Labour. It may more enthusiastically embrace closer alignment with the EU. And it may not be quite so embarrassed by the many genuinely left-wing things the government is doing, from tax to workers’ rights.

This may or (more likely) may not help. But the point is this: the identity of the chief of staff three and a bit years out from a general election, to a prime minister with a massive parliamentary majority, should not be determining these outcomes! That it may well do is the principle weakness of this Downing Street, not the appointment of Peter Mandelson to Washington.

Labour 🤝 Spurs — give it to Ange for the rest of the season.

The ability to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory. Or, in the eternal pre-match words of Sir Alex Ferguson: “Lads, it’s Tottenham.”

Good thesis, in principle, Jack, but not in this case. Starmer is seen to have acted on the self-admitted advice of Mr Morgan. So in this case, the identity did matter. Moreover, what on earth is an ambassadorial appointment got to do with the chief of the SW1A 2AA operation? That it did have must reflect something, such as doubts from the off. They took a risk too far about a man whose pile of resignations can be bookended 28 years apart. 28 years, no less!

[I’ve promised you a break from my comments and it will happen one day!]