Farage's secret plan to stoke inflation

When politicians set interest rates, there’s always a cost

What did George Osborne never do, Gordon Brown just once, and Nigel Lawson practically every lunchtime and twice on Sundays? Get your mind out of the gutter. The answer is: raise interest rates.

On 6 May 1997, the new Labour government surprised pretty much everyone by granting operational independence to the Bank of England to set monetary policy. No discussion, no consultation, just shock and awe. It remains one of the central legacies of the period, but one that has come under increasing pressure.

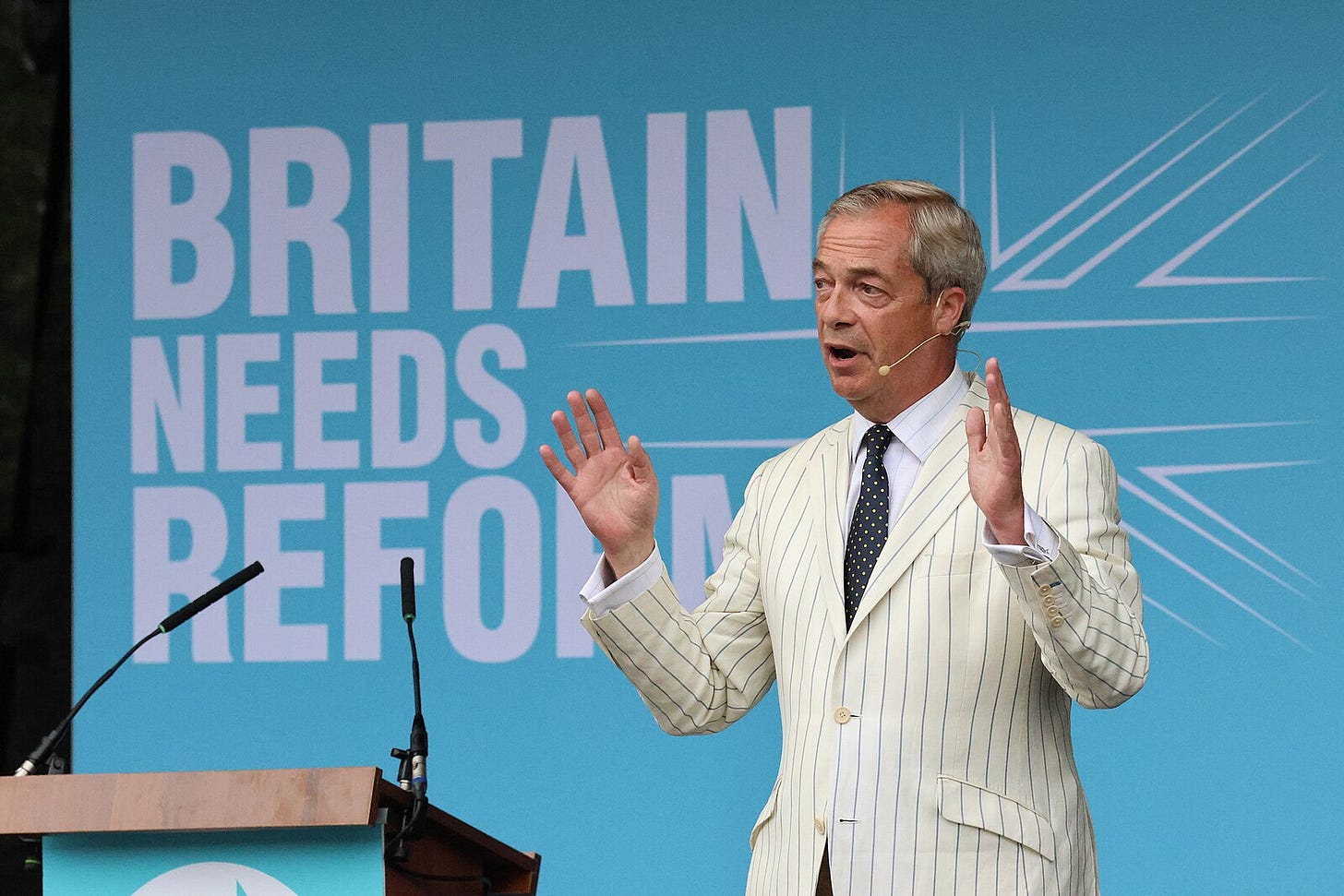

In an interview with The Times last week, Reform UK deputy leader Richard Tice suggested he was open to ministers having greater oversight over the Bank, including direct influence over interest rates, via the appointment of “one or two” government representatives to the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC).

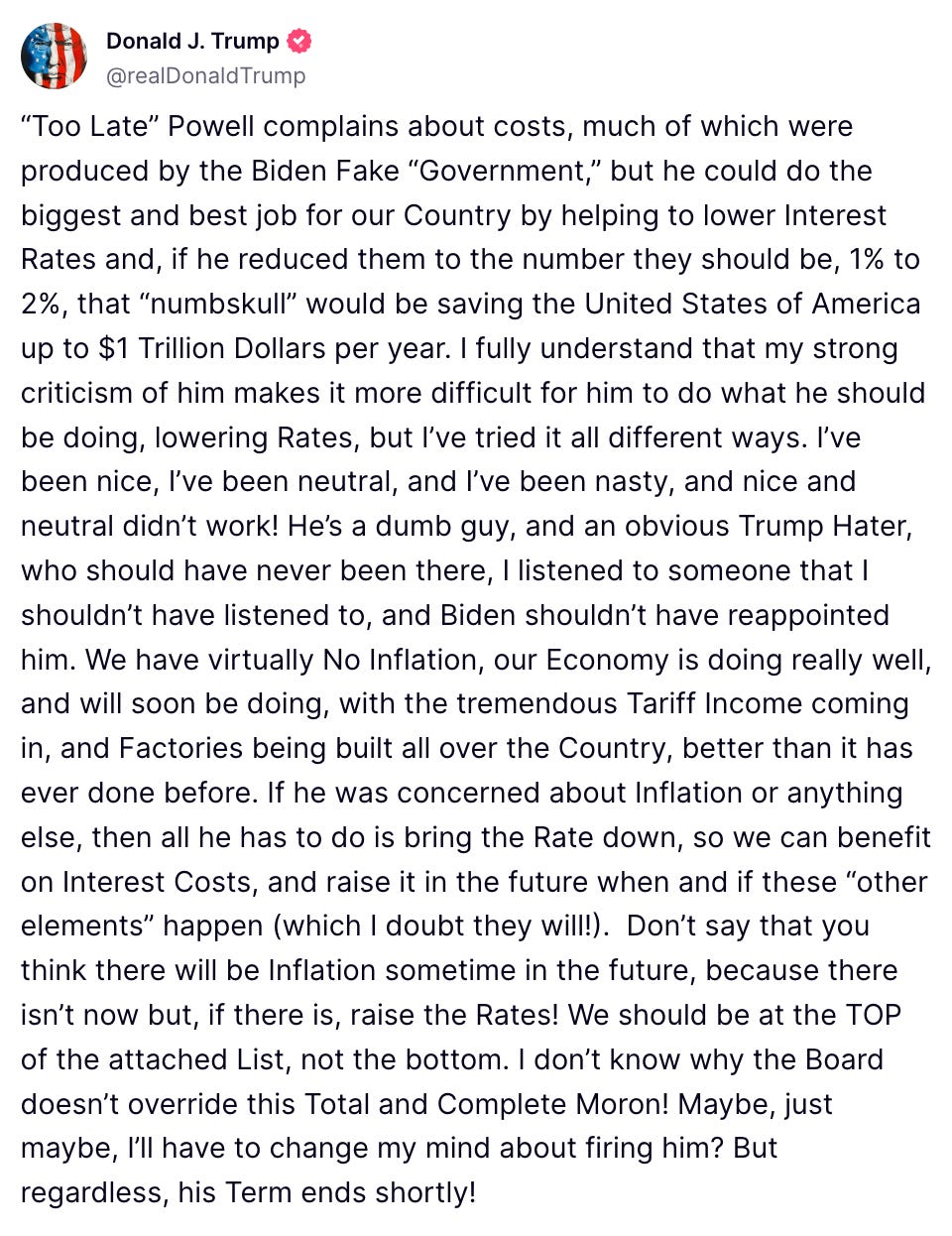

This is frankly mild stuff compared with what the President of the United States has been saying. Taking a break from threatening to give away the attack on Iranian nuclear facilities via his social media posts, Donald Trump called Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell a “Total and Complete Moron”, revealed he might try to fire him and suggested it was the central bank’s job to manage the US government’s borrowing costs.

The point about Bank of England independence is that, all other things being equal, it delivers lower inflation and reduced government borrowing costs. The reason is fairly simple: politicians face elections, and therefore pressure to avoid unpopular decisions such as making voters’ mortgages more expensive. Whereas central bankers are largely insulated from such concerns.

Of course, not even bankers enjoy social opprobrium. As William McChesney Martin, Federal Reserve chair from 1951-1970, famously quipped, the Fed is “in the position of the chaperone who has ordered the punch bowl removed just when the party was really warming up.”

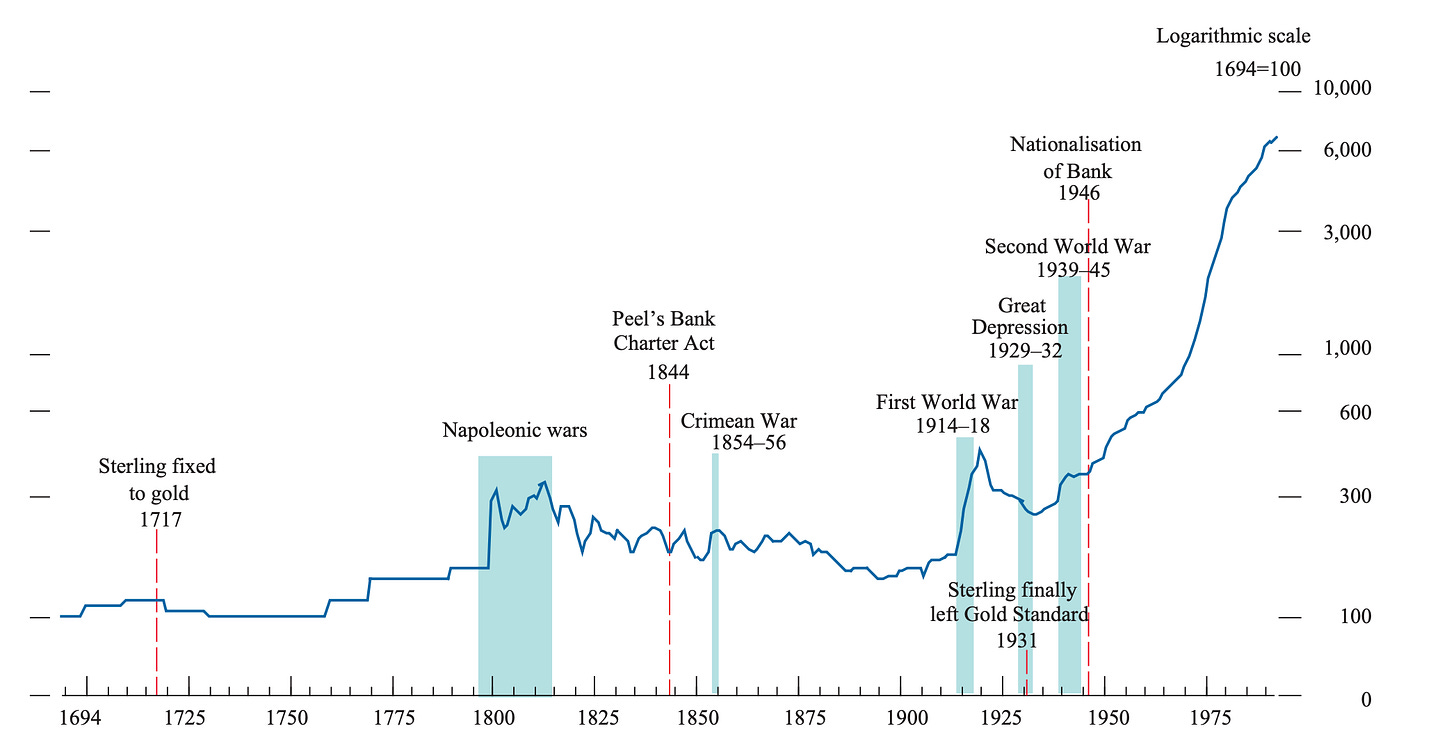

The economic history of post-war Britain has been one of occasionally wild parties followed by horrifically bad hangovers. In the 1970s and 1980s in particular, price stability — the building block of economic growth — was consistently conspicuous by its absence. This is bad because high inflation distorts price signals, deters investment and disproportionately impacts those on fixed incomes, who are least able to cope.

It all really began in 1971 with the collapse of Bretton Woods. Actually, I’m being polite. Richard Nixon collapsed the damn thing. Following the end of the Second World War, the value of currencies such as the pound had been fixed relative to the US dollar, whose value was in turn expressed in gold at a congressionally-set price of $35 per ounce.

But on 15 August 1971, America abruptly ended convertibility of the dollar to gold, known colloquially as the “Nixon shock”. Consequently, the UK lost what former Bank Governor (I believe he has a new job now) Mark Carney called its “nominal anchor”.

The long road to central bank independence

Below is a brief history of subsequent Great British attempts to combat inflation:

Incomes policies

Price controls

Monetary aggregate targeting

Exchange rate targeting

These all failed, either embarrassingly quickly or after a time. Consequently, prices rose by around 750% in the 25 years to 1992 — more than in the previous 250 years.

Britain’s entry into the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) is often thought of as being a precursor to joining the euro, but in reality it had a lot more to do with inflation. Margaret Thatcher talked a good game on price stability and sound money, but could never quite bring herself to go the whole hog. And so when Lawson, her increasingly unhappy chancellor, wrote to her in November 1988, advising that she accede to Bank of England independence, the prime minister declined.

But as her grip on power began to wane, Lawson’s successor, a certain John Major, convinced a reluctant Thatcher to allow Britain to join the ERM, with the pound shadowing the Deutsche Mark, piggybacking on the (independent) Bundesbank, which had real credibility on inflation. In effect, the prime minister granted Bank of England independence to the Germans.

Unfortunately, sterling joined the ERM at a vastly inflated rate (£1 = 2.95 Deutsche Mark) and fell out of the mechanism on 16 September 1992 — Black Wednesday — after which the Conservative Party lost its reputation for economic competence and never quite forgave the European project. Yet from this mess arrived something rather good: inflation targeting, which became the clear objective of monetary policy.

The benefits of independence were instant. As former Deputy Bank Governor Paul Tucker notes, long-term gilt yields fell by 50 basis points. And of that, economists later estimated that half could be attributed to the lower risk premium charged by the markets. That is, the people who lend Britain money were more confident that inflation would be lower and less volatile. This reduced the real cost of government debt by a remarkable 10%.

Yes, the Bank has made mistakes — no central bank foresaw the full inflationary consequences of Covid stimulus and supply chain shocks. But the benefits of independence are tangible, measurable and widely felt. By keeping a distance between politicians and interest rates, we get lower inflation and borrowing costs.

The idea of handing rate-setting powers back to politicians may masquerade as democratic accountability or revenge against technocratic elites. In reality, it is dangerous populist bluster. I mean, do you really want Trump, Tice or Farage in charge of the punch bowl?

Thank you for the summary of economic policy since the founding of the Bank of England in 1694. One of the principal founders went on to become part of the Darien Adventure which bankrupted Scotland and facilitated the Union of Scotland with England. The offer to pay compensation to the holders of the Darien Stock swayed the Scottish Lairds during the two days they spent debating the surrender of Scottish Sovereignty. The Pound was worth just over $4 in 1945, and vastly overvalued which greatly hampered our exporters. Eventually it was devalued by Wilson to $2.40 in 1966 and floated by Heath in 1971. Goodbye to all the crises caused by trade deficits causing successive governments to restrict economic activity by raising interest rates. Finally Thatcher closed down most of our heavy industry and coal mines and ushered in the modern world where the financial services industry controls most of the activities the rest of us pursue and charge us for the privilege.