The party that never quite works

The enduring appeal — and repeated failure — of blending social conservatism with left-wing economics

I could have been a millionaire. Many years ago, I opened up a kitchen cupboard and removed two jars. In the absence of adult supervision, I used a steak knife to merge two hitherto alien substances. Sweet yet salty, crunchy yet smooth: this was the first known attempt in human history to combine chocolate and peanut butter. As it transpired, others had gotten there first. But I take comfort in the knowledge that I came to it independently.

Every so often, a political entrepreneur stumbles across what appears to be the greatest untapped market in British politics. If Labour offers left-wing economics and social liberalism, while the Tories do right-wing economics and social conservatism, why not cherry pick the popular bits of these platforms to create one of your own?

That is, a movement which blends social conservatism with left-wing economics. The pro-hanging, pro-winter fuel payments party, as it were. One sees this with Blue Labour and Reform UK. Indeed, Nigel Farage recently declared his party had replaced Labour as “the party of the working class”. And he has sought to further distinguish Reform from the Tories by committing to fully reinstate winter fuel payments as well as scrapping the two-child benefit cap.

Of course, this has been tried before. In Harold Wilson and James Callaghan, Labour produced two of the most socially conservative prime ministers of the post-war period. It is not for nothing that the historian Peter Hennessy described Callaghan as a man whose values “remained fixed at around 1948.”

To be clear, these views did not prevent the Labour governments they led from pursuing social reforms, although these were largely driven by Roy Jenkins, home secretary from 1965–1967 and again from 1974–1976. Eager to create what he termed “a more civilised, more free and less hidebound society”, Jenkins saw through the first Race Relations Act, which banned racial discrimination in public places and supported private members’ bills which led to the legalisation of abortion and homosexuality, amongst other things.

These reforms remain some of the few policies for which Labour in the 1960s and 1970s is fondly remembered. Because, from an economic, industrial and ultimately political standpoint, the Wilson and Callaghan governments were not unqualified successes.

Following the landslide victory in 1966, Wilson lost in 1970 to Ted Heath, stumbled back in 1974 thanks to the three-day week, and after five further years of chaotic governing — which culminated in their own industrial unrest and overseeing deep internal fracturing — Labour was ejected from office, not to return for 18 years.

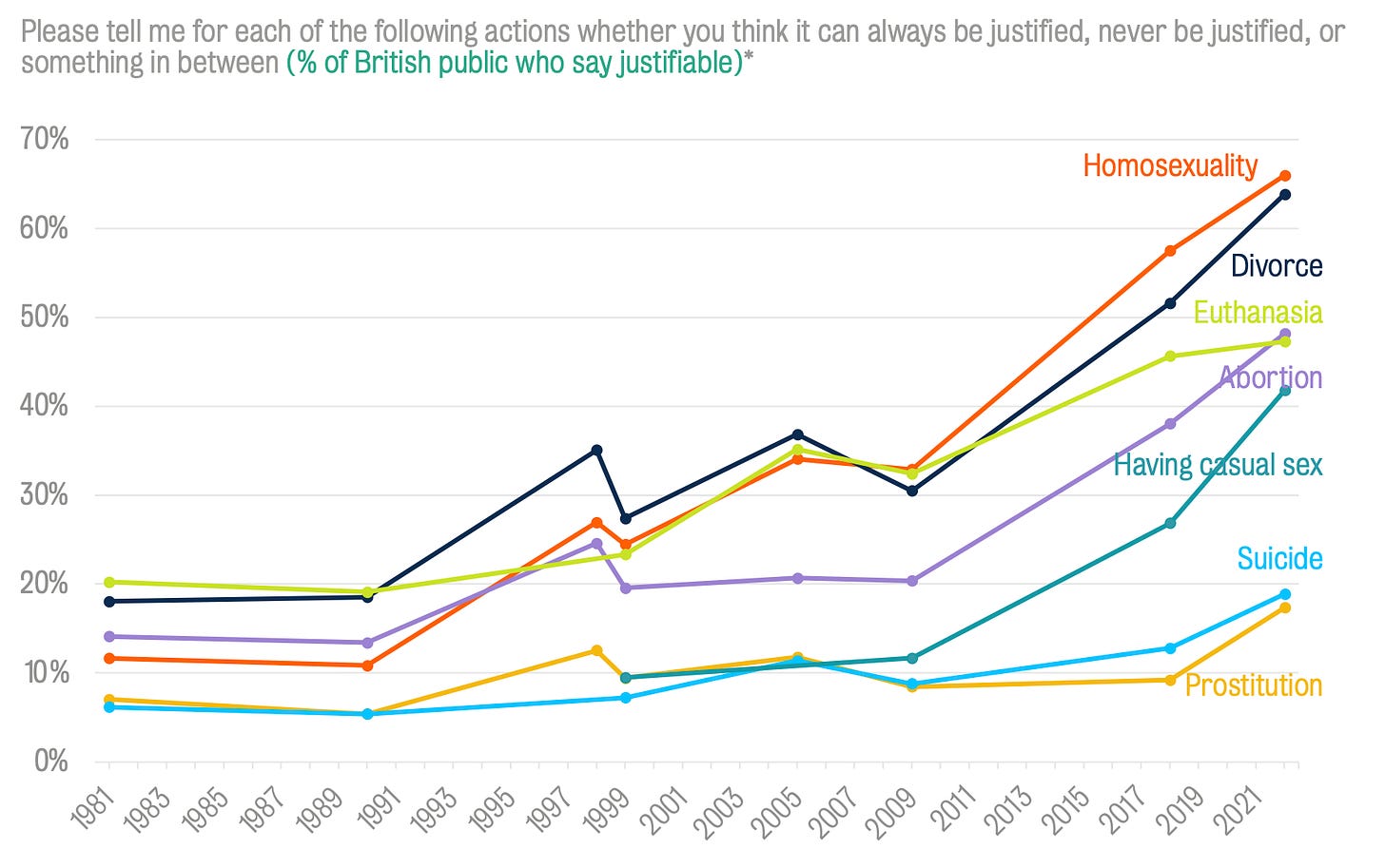

This is history, of course. Yet since then, the market for social conservatism has narrowed sharply. Data from the British Attitudes Survey finds that the UK ranks as among the most socially liberal countries in the world, characterised by marked shifts in views on a whole slew of issues. For example, two-thirds of Britons now say homosexuality is justifiable, up from 12% in 1981. As for divorce, support has risen from 18% to 64%1.

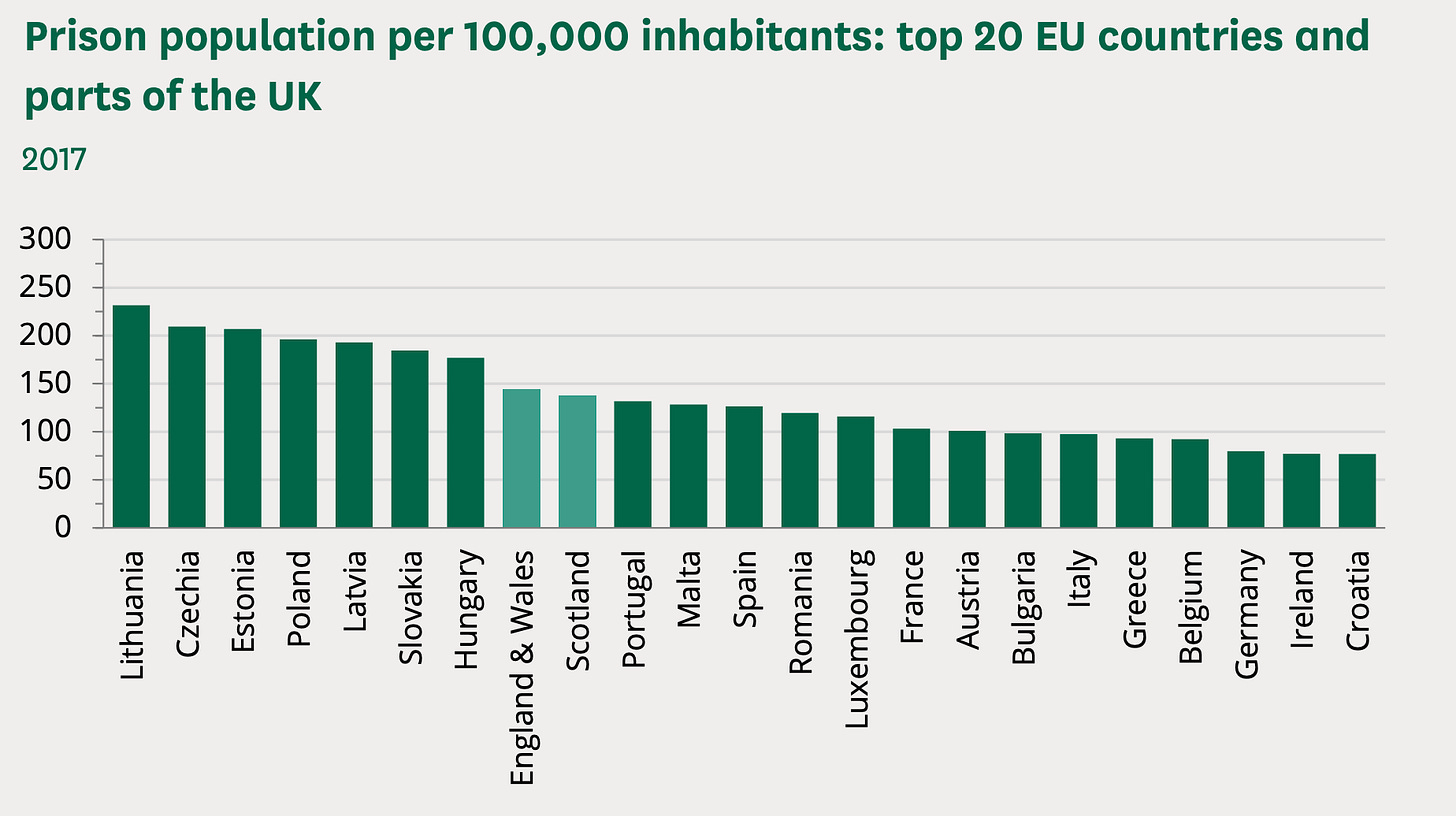

This is not to say there is no market for social conservatism. Britons remain death penalty curious, and are always open to locking up criminals. But the broad trend is clear.

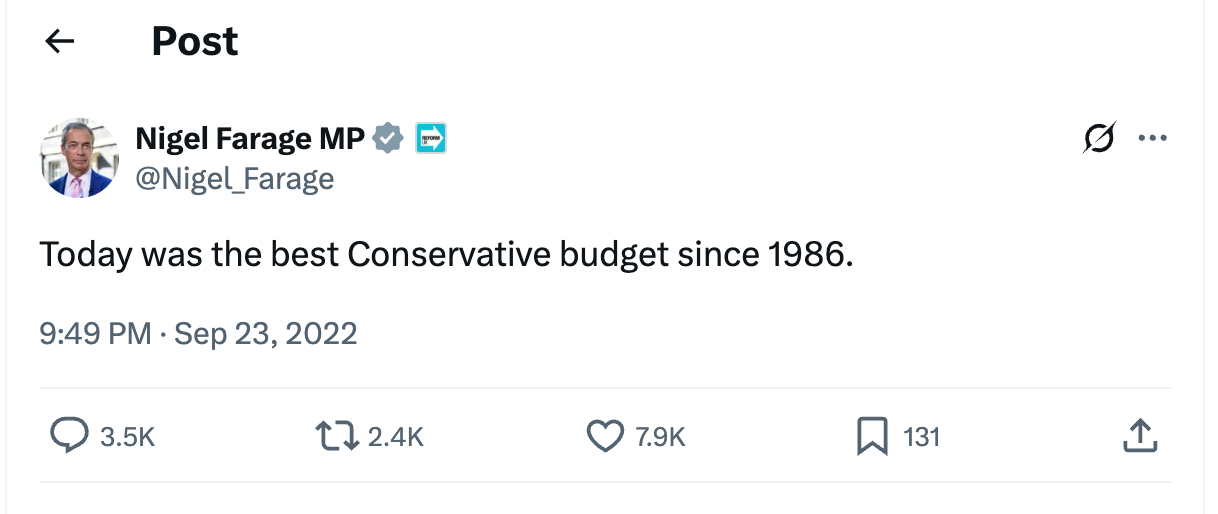

It is open to debate just how economically left-wing a Reform government would be in practice. Responding to Nigel Farage's speech last month, the Institute for Government’s Helen Miller described it as “very large tax cuts to be paid for with very large spending cuts”, with the latter very much unspecified. This is scarcely a surprise, given that Farage was one of the loudest cheerleaders for Liz Truss’s disastrous ‘mini-Budget’, which he labelled at the time, "the best Conservative budget since 1986".

If Reform UK continues to notch up by-election wins and makes further gains in local government — perhaps even edging toward national power — it will owe more to the fragmentation of the UK’s party system, persistent economic malaise and the appeal of being an insurgent party than to any coherent ideological breakthrough.

And yet, the elixir of blending social conservatism with left-wing economics will no doubt continue to tempt political entrepreneurs.