Rachel Reeves and the illusion of control

The unreleased eighth Harry Potter book

Trey Parker and Matt Stone, creators of South Park, the profanity-filled animated sitcom, had a go-to phrase: The Simpsons already did it. That is because they would often come up with plot ideas that The Simpsons — thanks to its deep reserve of writing talent and sheer longevity — had already done. Things got so bad that the seventh episode of the sixth season of South Park was called “Simpsons Already Did It”.

My equivalent in this instance is Giles Wilkes, a former Number 10 advisor and now partner at Flint Global and senior fellow at the Institute for Government. Last week, Wilkes wrote a terrific piece on his blog, with the charming headline: There really is no getting out of this fiscal corner. I read it just before bed (hey, I don’t tell you how to unwind) and promptly fell asleep. You’ll never guess what happened next.

The following day I awoke, convinced I’d thought of this great idea for a newsletter. Specifically, how the government’s problem is not the fiscal rules per se but rather the fiscal reality. Fortunately, I remembered the source of inspiration before I’d sent the script off to be animated. Here’s the part I most wish I’d written:

The fiscal rules are not perfect, and the government (over)reaction mid-year to events framed by those rules is pretty suboptimal. But they are also quite irrelevant. The government’s financial position is objectively bad.

How to get kids to eat their veggies

Read any parenting advice and you’re sure to come across the illusion of choice. So you don’t demand little Hugo or Beatrice eat their broccoli but instead ask them politely, “Would you like green beans or broccoli?” Of course, this sort of thing is not just for kids. Feeling as if we have agency is critical at all stages of life.

Well into her eighties, my grandma would blow on her dice during particularly stressful moments of Monopoly1. Even in games largely determined by chance, it is nice to at least pretend some elements are under our control. And I think a similar phenomenon is at play between Rachel Reeves and the markets. But instead of dice blowing, we have the fiscal rules.

The rules themselves don’t really matter for the purpose of today’s newsletter and I’m sure you don’t need reminding of them, but just in case:

The current budget should be on course to be in balance or surplus by 2029/30

Net financial debt should fall as a share of the economy in 2029/30

These represent a genuine constraint on government borrowing. But they are also what magicians call ‘misdirection’. First, because the rules are still pretty loose. And second, they allow us to pretend that the said constraints are self-imposed rather than demanded from on high.

The markets decide

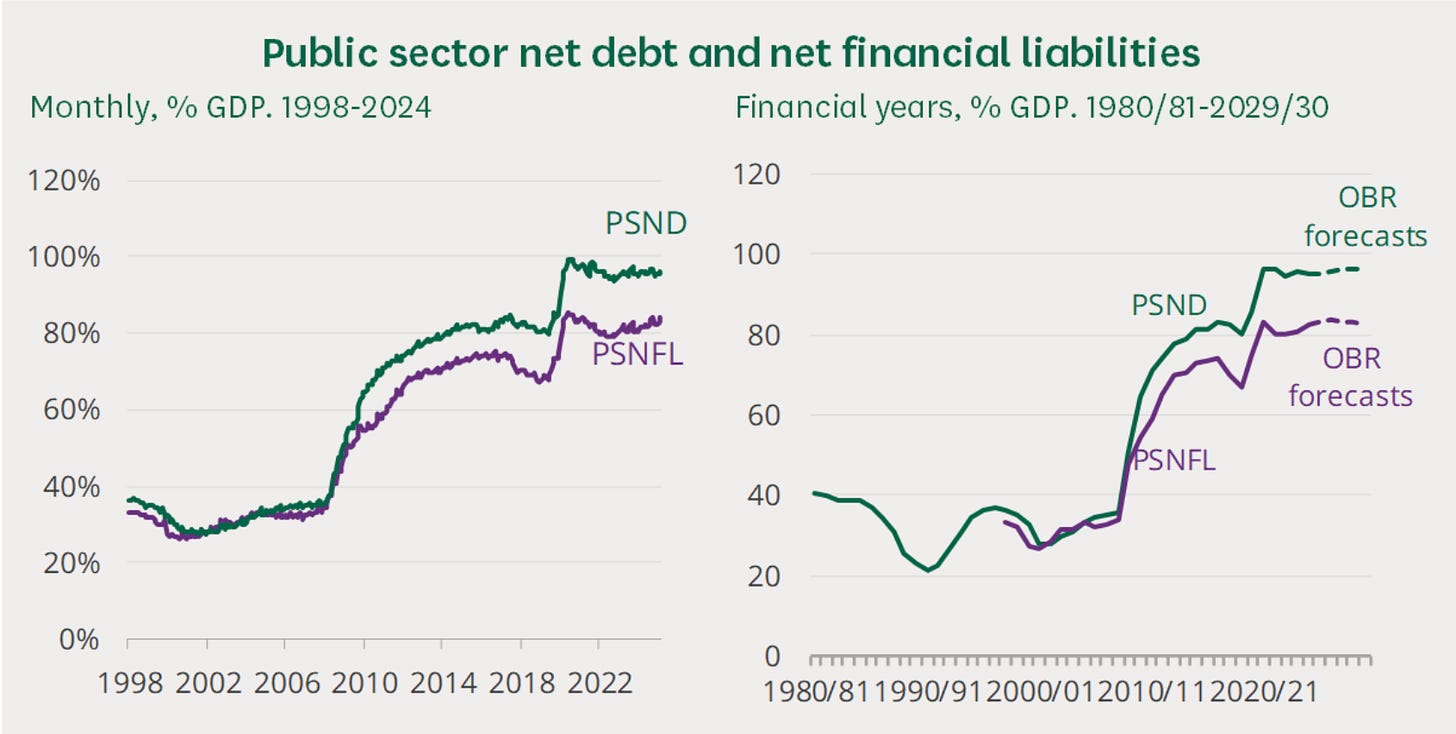

Britain’s fiscal position is not good. Public sector net debt is 96.4% of GDP (it was well below 40% in the 2000s), borrowing costs are high (as Paul Johnson of the Institute for Fiscal Studies notes, a full two percentage points higher than Germany) and forecasts for economic growth keep getting downgraded. Just yesterday, UK borrowing came in at a higher-than-expected £20.7bn in June, driven by rising debt costs.

As discussed, the chancellor’s fiscal rules are not a total smokescreen. But nor are they the ultimate constraint. That is what the markets will bear. And we have witnessed — not only following the disastrous Liz Truss mini-Budget but also in recent months — that they believe the UK government is, like Icarus, flying rather close to the sun.

It is fair to say that the gilt markets got a little jumpy when Reeves cried in public. But they did not suddenly go, “See! A girl can’t be chancellor, we’re going to have to charge you more for debt!” Instead, they were spooked by rumours that Reeves might resign or be removed, and that her replacement would further loosen the government’s fiscal rules.

Clearly, these rules matter a great deal — they are why Reeves has to go hunting for money every time the Office for Budget Responsibility cuts its growth forecasts. But they are ultimately a political constraint as much as an economic one. The chancellor and her fiscal rules are not quite the equivalent of the child who races to the front of the DLR to live out their dream of pretending to drive the train. But let’s not kid ourselves — the illusion serves much of the same purpose.

That is, all games of Monopoly

The problem is Brexit but the solution cannot be to rejoin because Farage would win the next election. So it’s down to subtle changes in existing taxes. Where do we start? The most obvious is the tax relief on pensions. This is 20% for most of us and 40% for those paying 40% tax and above. Why should a rich person get twice the tax relief as the majority of taxpayers? At one time they were able to put over a £1 million into their pensions. Make 20% the maximum tax relief on pension savings. Second anomaly is that much of the wealth of the Upper Echelons of our class system is held in land. As it never changes hands, it is not included in the Land Registry so changes in value are not taxed. This should be changed by requiring all land ownership to be registered with the Land Registry and taxed on change of ownership as part of inheritance tax. Yes, I know it is all held as Trust Funds but it is time that increases in the value of Trust Funds was taxed as capital gains. This would resolve the issue of a Wealth Tax. Yes, I know that the Royal Family would insist on being excluded but they could do as the previous Prince of Wales did and pay a voluntary tax calculated by their staff specialists. Third, is the existence of tax accountants. There are a reputed 90,000 of these people whose sole purpose is the avoidance of tax on the people who employ them. That Brown and Balls added over 4000 pages to the tax regulations was a boom to them, making it impossible for non specialists to master the allowances that are tax free. There is only one way to deal with this problem and that is by fixing a maximum allowance for each tax bracket. Those paying Standard Rate get the Standard Allowance, including any pension contributions, and no more; those on the 40% Rate get a maximum allowance of 10% of their salary taxed at 40%, which includes their pension contributions; those on 45% get a maximum allowance of 15% of their salary taxed at 45%, which includes their pension contribution. Allowances for investments, which currently swallow up a considerable proportion of their tax liabilities, will be treated separately and outside the tax system.