How to avoid raising taxes

Underpinned by a checklist of increasingly implausible assumptions

Everyone seems to agree that tax rises are inevitable in the autumn. But what if the latest Westminster consensus is wrong? Here, in no particular order, is a list of things you have to believe for Rachel Reeves not to have to increase taxes in the near future:

The economy grows faster than forecast

But earlier this month, the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) cut its GDP forecasts for the UK to 1.3% this year and 1% in 2026, down from 1.4% and 1.2%. Lower growth, along with its friend lower tax receipts, will shrink the chancellor’s already paper thin fiscal headroom.

There are no more exogenous shocks

Good luck with that. The markets are currently adopting something of a wait-and-see approach to the Israel-Iran conflict, but if strikes hamper Iranian oil facilities or force the closure of the Strait of Hormuz, they could rise sharply. This would feed not only into domestic petrol prices, but a wide array of goods and services, fuelling inflation.

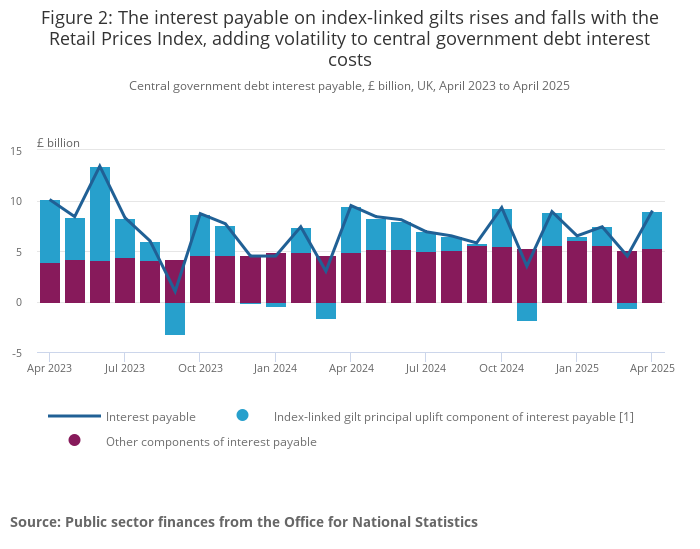

Speaking of which, higher prices would likely slow the already gradual pace of interest rate cuts. Bad news for borrowers of all kinds, whether household or sovereign.

The Labour government chooses to cut spending instead

Really? The same government that was forced into a U-turn over plans to take Winter Fuel Payments away from wealthy pensioners? Which was elected on a platform to repair crumbling public services, not least the NHS?

N.B. the bulk of cash in the Spending Review was focused on the first two years of the parliament. What odds that, in the two years before the next general election, the government simply shrugs its shoulders and says ‘no more nurses’?

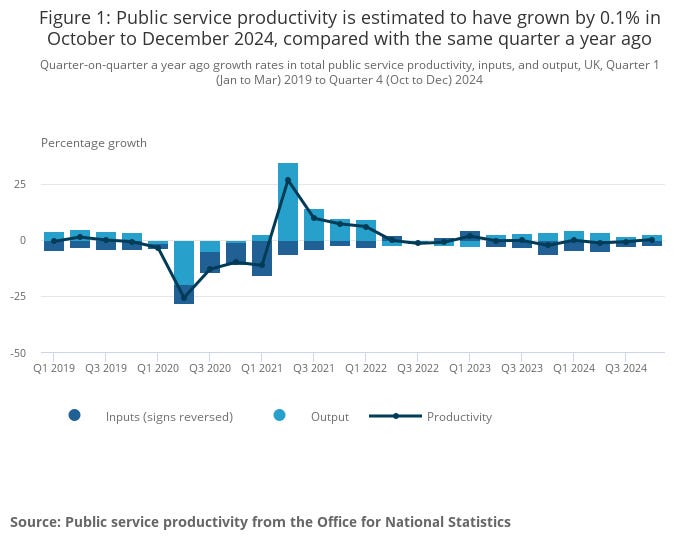

Public service reform will generate public sector productivity gains

Public sector productivity has been woeful in recent years. It was 4.6% below pre-pandemic levels in 2024, while healthcare productivity was almost 10% lower, according to figures from the Office for National Statistics.

In the Spending Review, the government declared its intention to “rewire the state”. This includes leveraging new technology to digitise services, fostering a culture that “relentlessly roots out waste”, establishing a “leaner, higher-skilled civil service” and “harnessing the power of AI”. Maybe.

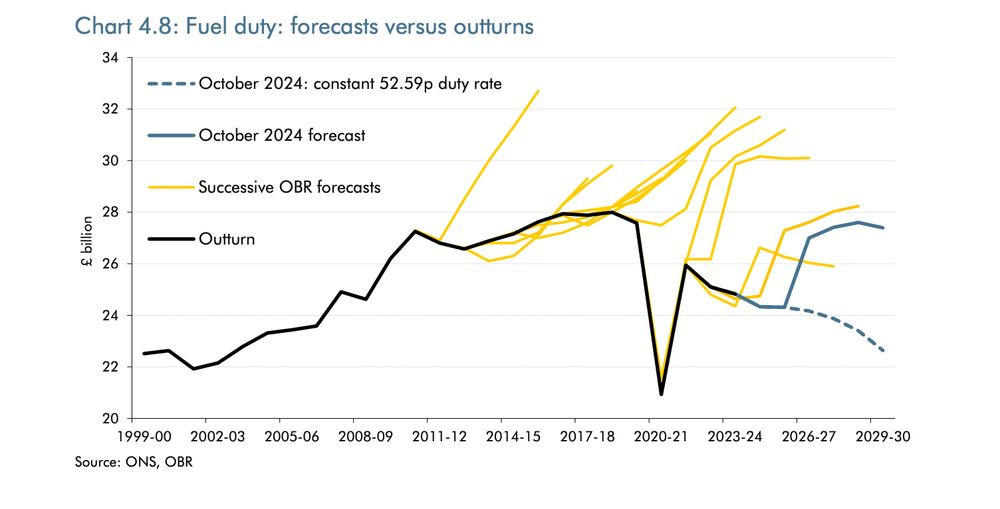

The 5p fuel duty cut will be reversed

Successive fuel duty cuts and freezes have cost the Exchequer north of £100bn since 2010. It is not for nothing that David Cameron described Robert Halfon, longtime campaigner on this issue, as "the most expensive MP in parliament".

The Office for Budget Responsibility forecast now assumes fuel duty will rise by 5p in March 2026 and uprated by inflation in every year from April 2026. Yet the reversal of the 5p cut has been delayed three times and fuel duty has not been uprated with RPI since 2011!

Britain’s enemies will decide to pack it in

The UK currently spends 2.3% of GDP on defence. In February, the government committed to 2.5% by 2027, and indicated plans to further raise spending to 3% in the next parliament. Nato appears to be pushing for 3.5%, but even 3% would require roughly another £20bn a year.

This can either be achieved by cratering the economy so the MoD automatically takes up a greater share of GDP, or by raising taxes. The government can only really cut international aid spending once.

Council tax doesn’t count as tax

Paul Johnson, director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies think tank, made clear what the government would rather keep quiet — council tax is set to increase significantly, perhaps by as much as 5% a year. This would send bills rising at their fastest rate since the 2001-05 parliament.

Ominously, the government has since stated that individual councils “remain responsible for setting their own council tax levels each year and the government is clear that they should put taxpayers first.”

Public sector pay goes away

The Spending Review made clear the Treasury’s position: funding for public sector pay deals must come from within existing departmental budgets, i.e. no more cash from the centre. Higher wages inevitably mean departments must allocate a larger share of their fixed cash budget on staffing costs if they hope to employ their existing workforce.

Higher inflation may also feed higher wage demands. As the IFS points out, public sector pay settlements have come in higher than forecast in recent years, averaging 5% in 2022–23 and 6% in 2023–24. Labour has also agreed to 5-6% deals, costing billions more than budgeted for.

Immigration has no impact on the economy

Regardless of one’s views on high levels of net migration, the OBR is clear: immigration boosts GDP, and therefore lower migration, as now expected following changes instituted by Labour and the previous Conservative governments, will lead to lower growth.

Productivity gains will definitely materialise this time

For all the accusations of negativity, the OBR has been consistently bullish about UK productivity. Professor David Miles, member of the watchdog’s Budget Responsibility Committee, recently called higher productivity “the almost pain-free route to fiscal sustainability”.

But what if the music stops, and the OBR finally accepts reality and downgrades productivity growth forecasts? Ben Nabarro, UK economist at Citigroup, told the Financial Times earlier this year that a reduction of just 0.1 percentage point in the OBR’s potential productivity growth forecast would create a hole of £7bn-£8bn in the public finances.

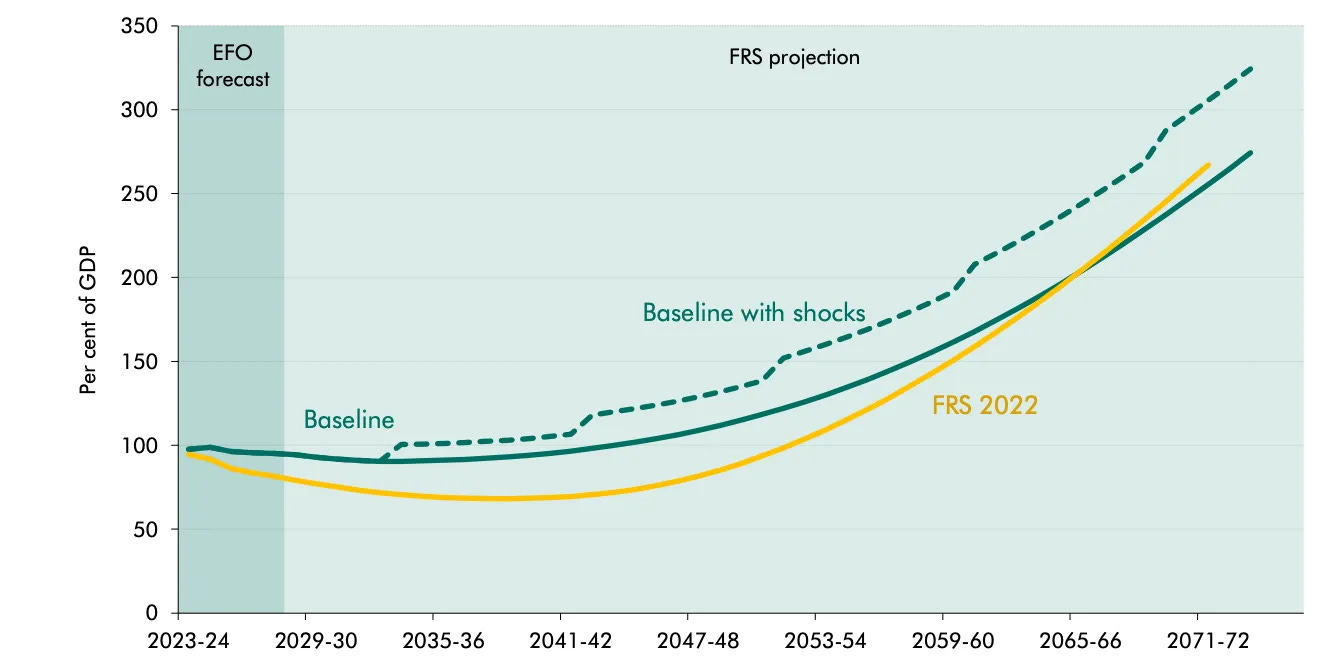

It gets worse

These are all short to medium-term pressures. In other words, they do not begin to account for the long-term challenge the British state faces from demographic change, a polite way of referring to our ageing society.

For the sake of length (it’s far too late to claim brevity), I’ll save which taxes may rise for another newsletter.

Well that's a jolly start to the week Jack!