The benefits of being an all-rounder

Why specialists might win the battle, but mastering multiple skills wins the war

In a sport such as Test cricket, there is always plenty to talk about. Which is just as well because, frankly, there is sometimes not all that much going on in the middle. Delays, reviews, drinks breaks, ball changes, fielding changes, bat changes, Jonathan Trott meticulously scratching the surface to death. Really, anything but actual play.

But there is one question on which everyone agrees, so much so that it is scarcely even discussed: who is the greatest of all time? The answer is considered so obvious, such a given that a debate might in actual fact omit him from the list. It reminds me of the story David Foster Wallace told in his celebrated commencement address to Kenyon College students in 2005:

"There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says 'Morning, boys. How's the water?' And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, 'What the hell is water?'"

For the Americans who read this newsletter, the water in this context is Donald Bradman. The Australian averaged 99.94 in Tests, roughly 40% higher than the next player on the list. In a world where sports scientists dedicate their lives and franchise owners spend billions of dollars to eke out marginal gains, this is something of an absurdity.

Consequently, there is no Messi vs Ronaldo, Djokovic vs Nadal or Babe Ruth vs Willie Mays in cricket. Everyone is fighting it out for silver. That is, unless you come at the question differently. Bradman is the best batsman, no doubt. But the best cricketer? This is where things move beyond statistics and into the realms of philosophy. Shouldn’t that be an all-rounder — someone who can not only hit centuries, but also the top of off stump?

All-rounders are often seen as heroic, almost fantastical figures. People still refer to ‘Botham’s Ashes’ of 1981 and even a single Andrew Flintoff over in 2005. Any list of the all-time greats includes the likes of Garfield Sobers, Jacques Kallis, Imran Khan, Keith Miller, Richard Hadlee, Kapil Dev, Shakib Al Hasan and Ian Botham. But one name often goes unmentioned. And what is the point of having your own newsletter if you can’t make a case for your favourite?

Ravindra Jadeja has a claim to being the greatest, least famous (outside of the subcontinent, anyway) active sportsperson today. He averages 38 with the bat, 25 with his left-arm spin and also happens to be a gun fielder. He is like that guy at school who excelled at football, maths and drama. You hated him, only because you wanted to be him.

But Jadeja, like any all-rounder, cannot be reduced to raw numbers. Players who can bat and bowl have the effect of elongating a line-up, because they enable the team to field an extra batter or bowler, depending on conditions. The advantage of having a genuine all-rounder (as opposed to a bits and pieces cricketer who can perform both skills, but badly) is tantamount to ball tampering.

Not only because of the additional runs and wickets provided by the all-rounder themselves, but the psychological impact on the team. The journalist, author and shouty Australian, Jarrod Kimber, coined the ‘Evan Gulbis effect’. Essentially, it means that a team’s top order batters, either consciously or unconsciously, bat slower and more defensively when they fear there is not enough good batting further down the line-up. But if you have an all-rounder in your side, everyone relaxes and can play more attacking shots.

Of course, you don’t need an all-rounder to be an era-defining team. Australia dominated Test cricket from around 1995-2007 without one, as did West Indies in the 1970s and 1980s. But the Aussies could simultaneously field Shane Warne and Glenn McGrath, two of the greatest bowlers in history, plus Adam Gilchrist keeping wicket. Meanwhile, West Indies were… West Indies.

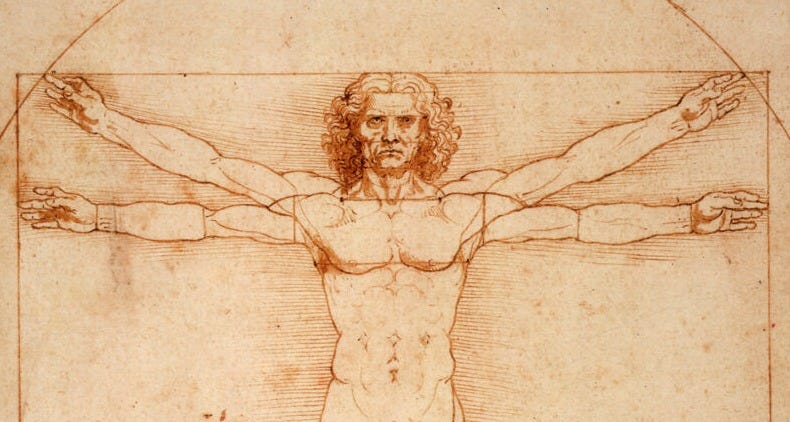

Still, in an era that fetishises specialisation, all-rounders stand out as something of a throwback to an earlier, less codified era. One where Leonardo da Vinci could paint and invent. Marie Curie could win Nobel prizes in two separate fields. And Theodore Roosevelt could be an explorer and a president.

They also serve as a reminder that not every skill can be quantified, and that greatness is not simply about mastering one discipline better than anyone else, but about doing many things well enough to elevate an entire team. And in the modern game, no one does that quite like Jadeja.

I don't have the knowledge to meaningfully disagree, or agree, with your championing of Jadeja. But do you not feel it a little churlish not even to mention Stokes in your line-up?

Joe Root must be a contender.

Look at his catches and bowling wickets.