FPTP in a five-party world

First-past-the-post delivers stable governments and keeps extremists out. Except when it doesn't

From an early age, I sensed a fatalism deep within. It was one I simply could not shake, no matter my attempts at distraction. Being so young, I thought I was alone. And shame does funny things to us. But in the spirit of openness and in recognition of a new dawn, here is what I knew to be true: no matter how long I lived, I would never see anything as efficient as Labour’s 2005 general election vote share.

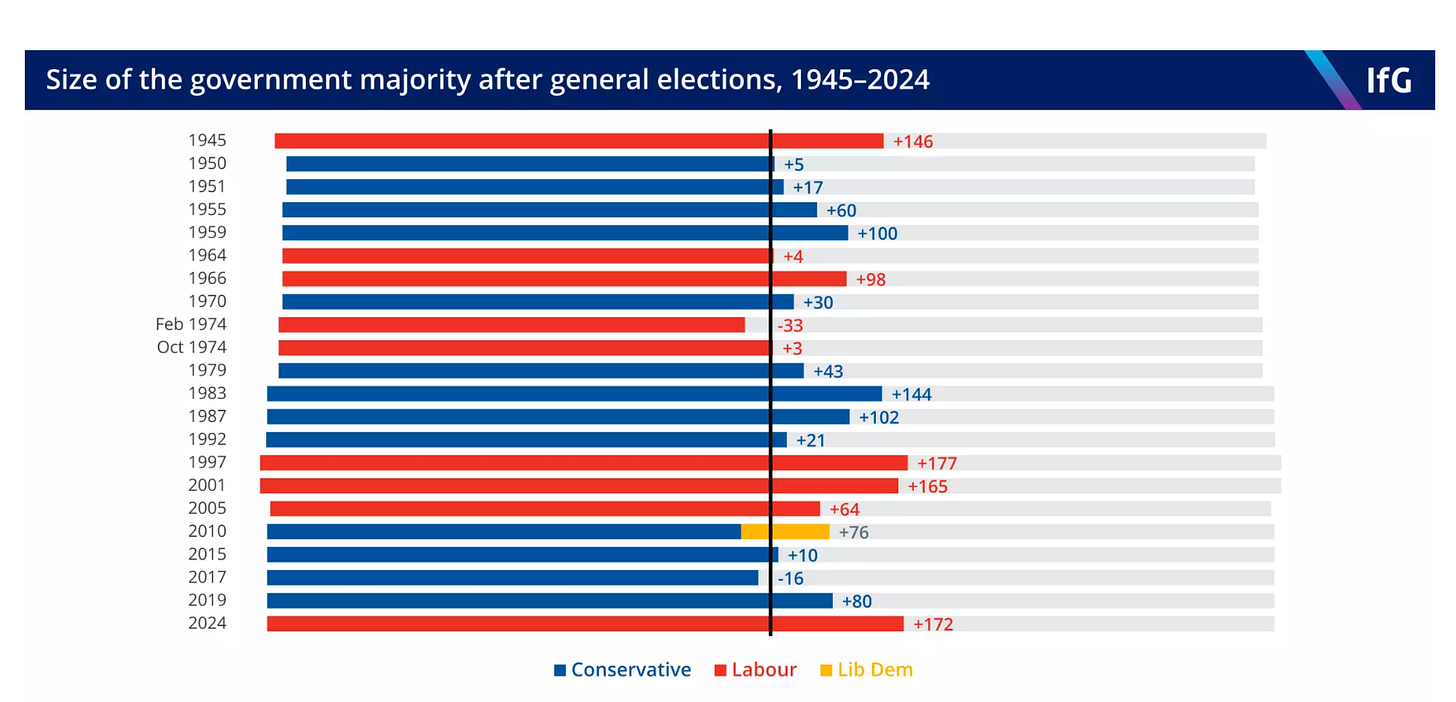

The party secured a historically healthy majority of 66 (around 55% of seats in the new House of Commons) on 35.2% of the vote, ahead of the Conservatives on 32.4% and the Liberal Democrats on 22%. It took nearly two decades, but I finally found closure early in the morning of 5 July 2024, when Keir Starmer won a majority of 166 (63% of seats) on just 33.7% of the vote. I was finally free.

This is not a criticism of first-past-the-post (FPTP) by the way. And anyway, electoral systems are not sentient beings. In this instance, disproportionality is a feature, rather than a bug. FPTP’s strengths are in delivering stable governments and keeping extremists out. Except when it does not.

First, about those stable governments. If we say that a decent majority in the Commons is 50 seats, then we can see that FPTP frequently fails to deliver. In 11 of the 22 general elections since 1945, the largest party failed to achieve that target.

Then there is the extremism defence. Here, FPTP has at first glance a better record. Say what you like about Harold Wilson’s paranoia or John Major’s disintegrating authority, but Britain has not been taken over by radicals. Indeed, the criticism at times has been that the two main parties were too similar.

Of course, this ignores the phenomenon of internal extremism, or rather the ability of otherwise centre-left or centre-right parties to be captured by their flanks. Take Labour from 2015-2020, or the US Republicans since 2016. One could also point to the fact that in the 1970s, even as Heathism was in full flight, around three dozen Conservative MPs were members of the ultra-right-wing Monday Club. FPTP can keep out fringe parties, but not necessarily fringe ideas.

But FPTP starts to face stresses when two-party systems break down, and this threatens to become a crisis of confidence in a full-blown multi-party system. Which is where the UK is now.

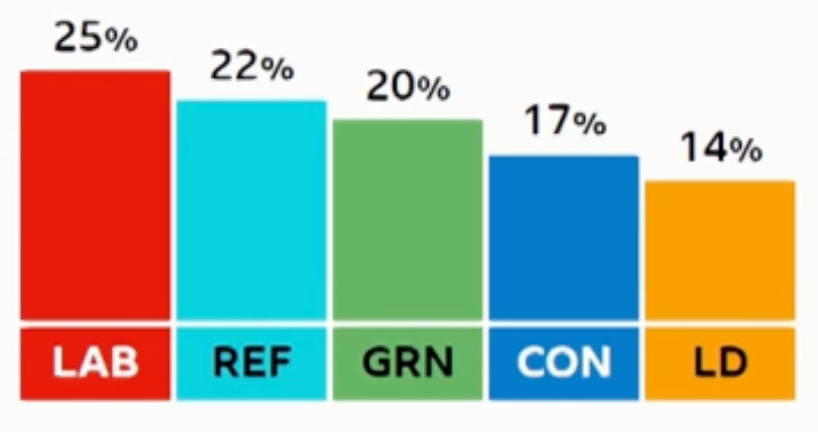

Take yesterday’s West of England mayoral election, which went something like this:

Labour: 25%

Reform UK: 22.1%

Greens: 20%

Conservatives: 16.6%

Lib Dems: 14%

These sorts of elections (that is, mayoral as well as Police and Crime Commissioners) used to be held under the supplementary voting system (STV), but were changed by the Tories in government to, let’s face it, improve their chance of victory. Labour is likely to switch it back.

Alan Renwick, Professor of Democratic Politics at University College London and Deputy Director of the Constitution Unit, wrote last year that the change to the voting system switched approximately seven, but perhaps as many as 10 or 12, PCC races. “That is a remarkably large effect from a simple tweak to the rules.”

At the time of the decision to change the voting system, in 2021, the left of British politics was more split than the right. Hence why the switch from FPTP to STV favoured the Conservatives. Given the continued rise of Reform UK, that is not necessarily the case anymore.

Of course, there is no suggestion of a change to the system used for election to the House of Commons, despite pressure from Labour’s National Policy Forum, which noted that FPTP is “contributing to the distrust and alienation we see in politics” and a 2022 motion passed at Labour Conference backing a switch to proportional representation. Starmer remains unmoved. The difficulty, of course, is convincing any prime minister who has just won an election on a particular voting system to ditch it in favour of another.

Cards on the table time. No one has ever uttered the words “give me the supplementary voting system or give me death”. And believe me, I have spent enough time with people who can talk of little else than electoral reform. For now, we should expect many more elections to be won on something between a quarter and a third of the vote.

Perhaps the biggest chance for change, for those who want it, is that now the right of British politics appears to be as split as the left, giving both main parties pause for thought.

Fptp does not encourage cooperation and consensus and that is what delivers stable government.

Interesting analysis and what if you have a six or seven party split an Scotland or Wales or NI?