Small boats weren't the first choice

The UK cracked down on lorry smuggling. Migrants found another way

In 2023, Rishi Sunak made “stopping the boats” one of his five key policy pledges. The following year, Keir Starmer called it his "personal mission to smash the people-smuggling gangs". Small boat crossings have become a totemic political issue for both left and right. Yet this was not always the case. In fact, until relatively recently, it was scarcely an issue at all.

A total of 36,816 people crossed the English Channel in a small boat last year, a rise on 2023, though less than the record of 45,774, set in 2022. Yet the figure for 2018 could be measured in the hundreds. What explains this enormous change in such a short period of time? Before we come to that, a little background on the type of people who come to Britain by small boat, and what happens to them once they get there.

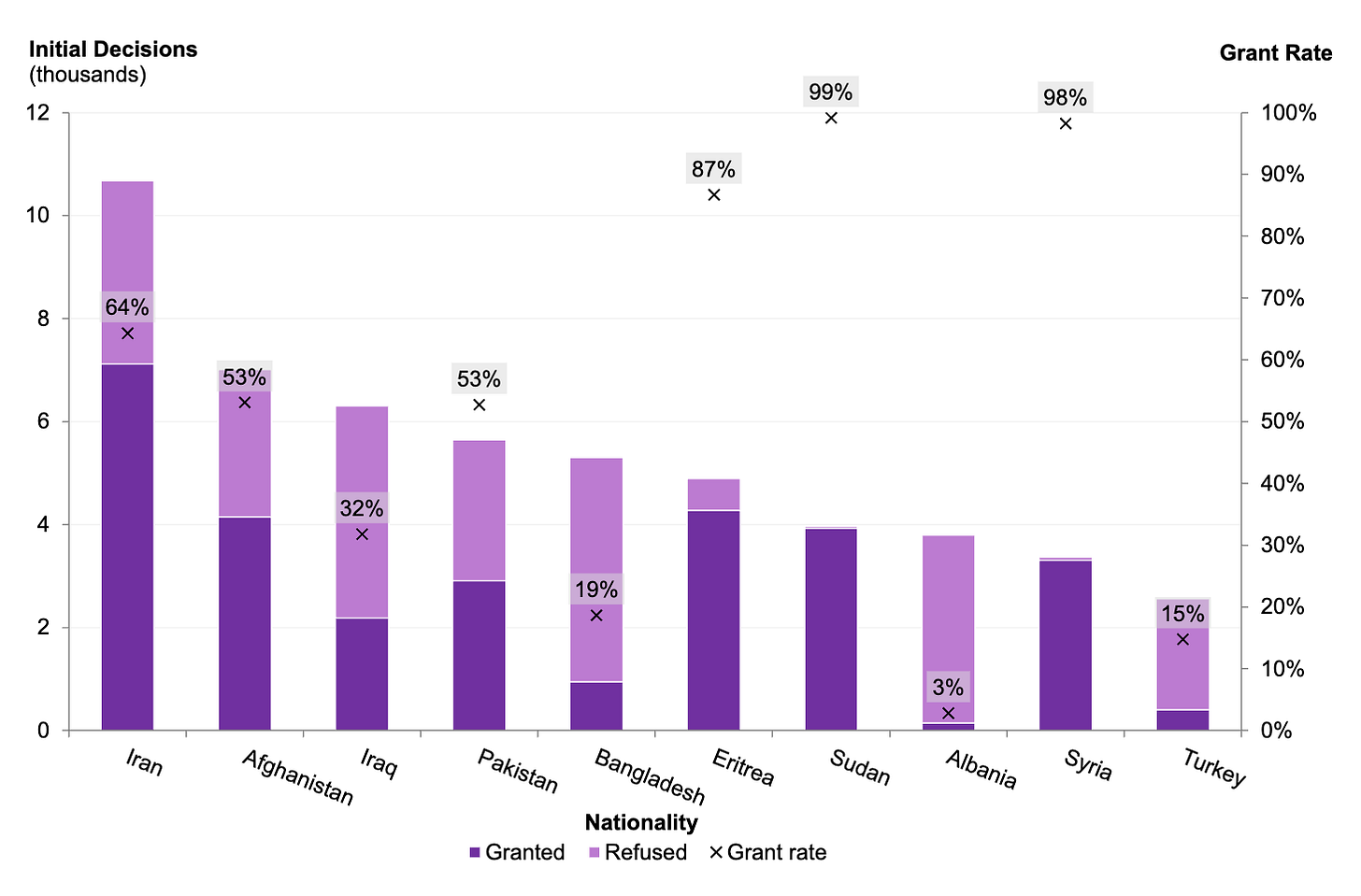

Analysis by The Migration Observatory finds that 93% of small boat arrivals from 2018 to March 2024 claimed asylum, and of those who had received an initial decision, around three-quarters were successful. Indeed, the grant rate for migrants arriving in small boats has been higher than the average rate for asylum applications generally. This is largely because many of the most common nationalities for those on small boats, such as Afghan, Syrian and Eritrean, have some of the highest grant rates.

The short answer to the question posed above, is that many more people come by boat because alternative routes have been blocked off. At the peak of the 2014-15 migrant crisis, around 2,000 migrants a night were attempting to illegally enter the UK, mostly by concealing themselves in the backs of lorries travelling through the Channel Tunnel. Incursions into the port of Calais were a regular occurrence. For example, on the evening of 2 October 2015, train services were suspended when 120 migrants stormed the terminal on the French side.

To counter this, the UK and French governments invested vast sums to improve security fences around both the ports and Eurotunnel, installed CCTV and buffer zones as well as infra-red detection beams and vehicle screening cameras. Pressure was also placed on hauliers themselves. As of today, anyone found carrying a “clandestine entrant”, even if you are a tourist, can face a fine of up to £10,000 per person.

A 2020 report by the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration into the Home Office’s response to irregular migration found that this had “a huge impact on the number of migrants entering the port areas to stow away on lorries and trains bound for the UK.” When incentives change, people — including criminal gangs — change their behaviour.

The surge in small boat crossings began in the last quarter of 2018, which saw a four-fold increase compared with the first nine months of the year. By Christmas Day, the Daily Telegraph was reporting “Record number of migrants try to cross Channel”. Three days later, home secretary Sajid Javid declared the small boat crossings to be a “major incident”. Additional UK patrol vessels were deployed in the Channel as part of a coordinated response between British and French authorities.

The 2018 surge was, in the words of the Inspector’s report, unforeseen. Its conclusion is fairly stark, and worth quoting in full:

“[H]ad more decisive action been taken earlier to demonstrate that these attempts would not succeed, the small boats route may not have become established in the minds of many migrants and facilitators as an effective method of illegal entry, as the evidence would suggest is now the case. By the beginning of 2019, it was already much harder to stop this threat from growing, and by the beginning of 2020 it appeared to be too late.”

There were other factors at play, not least the dismantling of the so-called Calais ‘Jungle’ migrant camp in October 2016 and the growing professionalisation of people smugglers. There are also myriad push-factors. The return of the Taliban to Afghanistan, civil wars in Syria and Sudan, continued human rights violations in Eritrea and Iran. Meanwhile, accelerating climate change is causing widespread displacement. In 2022, disasters linked to the climate triggered more than half of new reported displacements, according to the UN Refugee Agency.

Irregular crossings into the UK are not unusual. But small boat crossings are a new phenomenon, and far more more visible and politically potent due to regular media coverage and dramatic footage. The government has clearly failed to demonstrate that it is an unviable route, despite the monetary and human costs.

Small boat crossings would fall (and the government could be said to ‘take back control’) if the UK increased the number of safe and legal routes. The reality is that there are precious few such routes for refugees to travel to the UK, and those that do exist are largely restricted by nationality (Afghanistan, Ukraine and people from Hong Kong).

Of course, more safe and legal routes may mean more people apply, and given the countries from which they come, more people granted asylum. Whether that is seen as a good thing by the government of the day is an open question.