The truth about London

It isn't love, it isn't hate, it's just indifference

I’m not sure it would have occurred to me to invent agriculture. Particularly when life as a hunter-gatherer wasn’t so bad. You could enjoy a varied diet, low rates of chronic disease and a fairly flexible schedule. It was not for nothing that the cultural anthropologist Marshall Sahlins famously described hunter-gatherers as “the original affluent society”, noting they only worked three to five hours per day to meet their subsistence needs, which allowed them to devote more time to leisure.

Compare that to the life of a typical human in early agricultural societies: poor nutrition, risk of starvation if a single crop failed and overcrowding that enabled the spread of parasites and infectious disease. Little wonder that the author Jared Diamond described the decision to switch to farming as “the worst mistake in human history.”

Take one example. When the anthropologist George Armelagos examined nearly 600 skeletons from Dickson Mounds, a Native American settlement site and burial mound in Illinois, he found that after intensive maize cultivation was adopted around A.D. 1200, cases of iron-deficiency anaemia jumped from 16% to 64%, while average life expectancy fell from 26 years to 19 years.

Yet the shift to agriculture — after 200,000 years of hunting and gathering — may have been less a conscious choice than a kind of gradual entrapment — driven by climatic shifts, growing populations and the allure of surplus food. That this revolution occurred independently across multiple societies around the world suggests that farming conferred a compelling advantage.

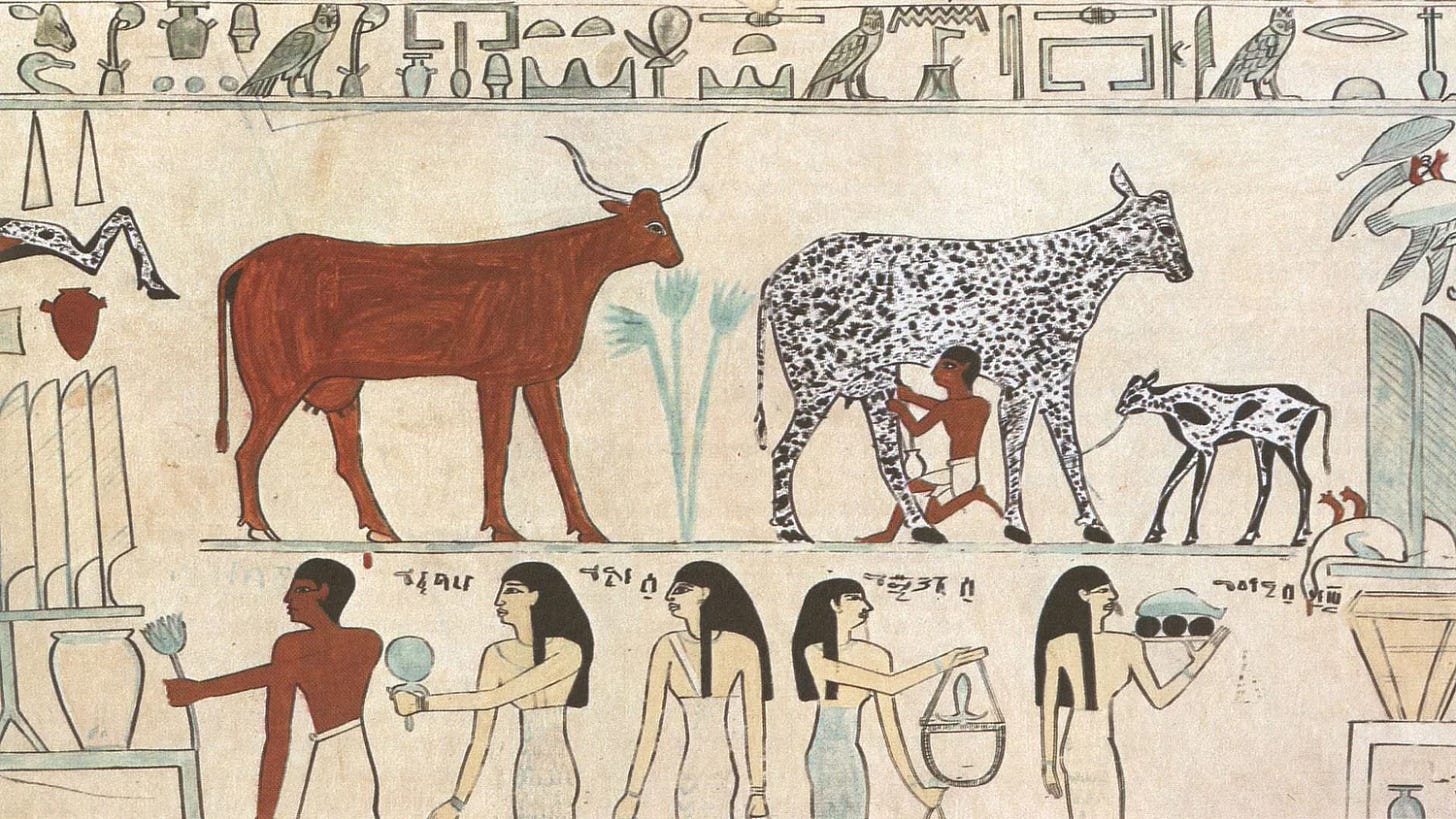

It enabled cities to flourish and civilisations to rise. To that end, the global population exploded, from around five million 10,000 years ago to more than 8 billion today. Farming could simply support so many more people than hunting — the catch was that it came with a poorer quality of life. It was a boon for homo sapiens, less so for individual humans.

London

The thing about London is that it does not care about you. Whether you are having a bad day or your wedding day. If it rains, it isn’t ironic. It’s a temperate maritime climate. It isn’t about you. Or any of the other nine or so million inhabitants. The city is gloriously impervious to everyone. It was there before you and it’ll be here long after you are gone.

London isn’t aspirational like New York, hypermodern like Tokyo or blessed with natural beauty like Sydney. Even Paris, with its segregated neighbourhoods and curated disdain, at least tries to impress you. London can’t be arsed. And the feeling is mutual. The concept of an “I ♡ LDN” t-shirt would get you sent to, well, Coventry.

I mean, has a city ever had less of a relationship with its own river? The Thames was once vital — trade, empire, industry. Today? I suppose you might take the Clipper if there’s a Tube strike, but otherwise, it’s something of an urban ornament we can’t quite bring ourselves to chuck out in case we might need it again one day. Like a drawer full of cables and chargers for devices we no longer own.

Success, the entrenched interest of incumbents and a sclerotic planning system have combined to drive vast housing wealth but also many people out of the city. Schools are closing. Pubs are shutting. Suddenly, your friends have moved to Zone 6 and still expect a welcome gift.

London has the power, like an older sibling, to make you feel tolerated, rather than welcome. In recent years, that feeling has sharpened for some — a tension hanging in the air, a weight you didn’t expect to be carrying across the streets you once unselfconsciously called home.

I suppose this is us getting off lightly. More than 100,000 years ago, subtle changes in the human mouth set the stage for something remarkable. Our jaws shrank, the tongue grew more agile and the larynx descended. It was another one of those good news/bad news situations. It enhanced our ability to make a wide range of sounds and tones, form tens of thousands of words, you know, gossip.

On the other hand, it meant that when we eat — and unlike in other primates — all food has to travel past the larynx and, crucially, miss it, in order to reach the oesophagus. Failure results in choking and, ultimately death. In other words, the ability to communicate was given preference over, well, not dying quite so frequently.

London probably won’t kill you, but it won’t perform the Heimlich manoeuvre either. That’s the deal.

Housekeeping: I’d love your feedback. This short, anonymous survey (one minute) will help me improve Lines To Take and shape what comes next. Whether you read every issue or just now and then — your thoughts really matter.

I’ve a love hate relationship with London .. born and bred here. Not sure I’d cope as well without the relatively close proximity of the Heath .

A whimsical piece that is just what is needed for the end of the week. Were you eating magical mushrooms last night?