Why people follow the rules

Or, why the Left should pick its battles with Robert Jenrick

“Rules are good! Rules help control the fun!” — Monica Geller, New York City, 1998

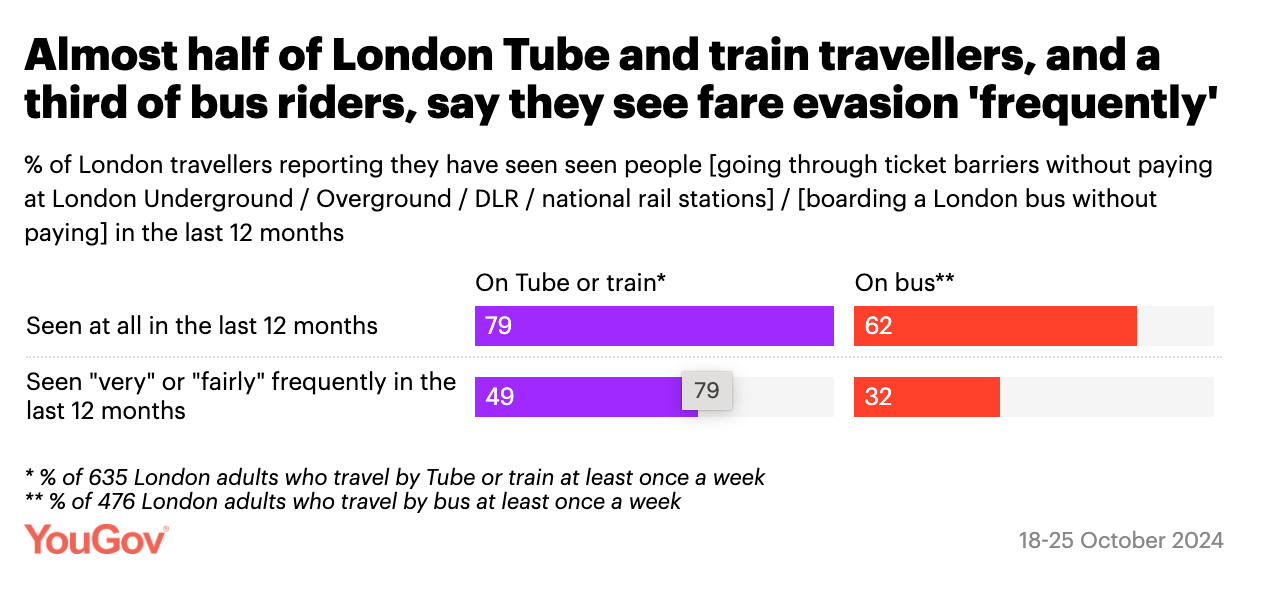

Traipsing through Stratford Underground station during rush hour is nobody’s idea of fun. And it is even less amusing when you see the person ahead of you (or more likely, feel the person tailgating behind you) slip through the barriers to avoid paying.

The natural reaction — once the frustration subsides — is to wonder why they do it. Perhaps they cannot afford it. Or they (correctly) assume the risk of being caught is low. Or they view non-payment as a form of protest. Or they think it is a victimless crime. Or they simply do not believe the rules apply to them.

But the more lively question is, given all of the above, why the vast majority (96.6% according to Transport for London) pay the fare. Happily, a recent paper in Nature by Simon Gächter, Lucas Molleman and Daniele Nosenzo seeks to answer this question.

The researchers conducted multiple sets of experiments involving a minimalist traffic light task. Participants were told to move a circle-shaped object to a red light and then to a finishing line. They received a starting pot of 20 money units, which visibly counted down by one per second. Their instructions were to move as quickly as possible to the finish line, which would suggest jumping the traffic light at any time. However, they were also explicitly told to wait until the light turned green.

The authors found that a majority of participants in their experiments (55%-70%) conformed to an arbitrary and costly rule. This held even if they were anonymous, alone and the violations were harmless. They did this out of respect for rules and an awareness of social obligations.

In other words, people adhere to social norms and rules independent of social expectations, preferences and incentives, out of an “intrinsic respect” for rules. Consequently, though external incentives (or sanctions) may enhance rule-following, they are not essential to achieve high rates.

Still, rule-breaking can be contagious. This is because humans are constantly studying how others act and adjusting their own behaviour in accordance. Think about how you might respond to a fire alarm in two scenarios. In the first, everyone immediately stops what they are doing, locates the nearest exit and leaves. In the second, the screeching siren goes completely ignored.

This dynamic has implications far beyond fare dodging. When rule-breaking appears common or goes unpunished, it can reshape public perceptions of fairness and fuel support for more punitive policies. This is especially evident in how public discourse and government policy approach welfare and the benefits system.

The idea that “everyone is at it” has buttressed policies such as the two-child benefit cap. Indeed, it is also seemingly shared by parts of the British state. Last year, a report by the Department for Work and Pensions acknowledged there is “an increasing trend in the underlying propensity towards fraudulent behaviour” in the welfare system and forecast fraud levels to grow by 5% a year.

Polling last July by YouGov found that six in ten Britons thought the two-child benefit limit should be kept, including half of Labour voters. This despite the fact that lifting the two-child benefit cap, as Labour now intends, is one of the quickest and easiest ways to alleviate child poverty.

In a world where breaches of the rules are often more visible than compliance, it is easy to believe that the former represents the norm. But the data tells a more hopeful story: most people follow rules not because they are being watched, but because they believe in the values of order, fairness, and social responsibility.

This matters when shaping public policy. If we assume everyone is out to cheat the system, we risk designing bad policy built on distrust, which in turn can erode the very norms that keep society functioning. The challenge is not simply to punish rule-breakers — it is to protect and reinforce the quiet instinct to do the right thing, even when no one is looking.

I am not sure how Jack Keesler started dropping into my inbox - but I have never read a bad article. Each is thought provoking.

Not a very surprising result, but it doesn't give much insight into the specifics of what can be done to counter the impression that lots of people are breaking the rules.

In the case of fare dodging, and some forms of shoplifting, this can be achieved by high levels of surveillance but much surveillance isn't visible, relying on technology (CCTV, etc) rather than the physical presence of ticket inspectors, etc, to save money.

Benefit fraud is a hot topic, though the sums involved are often small compared to major financial fraud, because we observe people around us, but in the UK we seem to treat the risks involved in business fraud as little more than a potential business expense rather than something that should bring shame and opprobrium. Tax dodgers risk a financial penalty, but rarely a criminal conviction and public humiliation.