Don't blame Wimbledon

Serve-and-volley may be dead — but the culprit remains at large

The Wimbledon public embraced Goran Ivanišević not despite his flaws, but because of them. He could be brilliant and erratic — often within the same point. Remember the “good Goran” and “bad Goran” personas? He was rarely far from self-sabotage, once reflecting: “The trouble with me is that every match I play against five opponents: umpire, crowd, ball boys, court, and myself.” He was never quite as good as Pete Sampras, but somehow more complete.

What no one could honestly say they loved about Ivanišević was his game. At 6ft 4in, the Croat boasted one of the best serves on tour which, in combination with his natural leftiness, meant a typical service game on grass would go something like this: ace, ace, service winner, double fault, ace. Fans would applaud, but more in the dutiful manner of a parent observing their offspring flinging themselves off a diving board in the Algarve.

You may have heard about who killed serve-and-volley, and that Goran is partly to blame. The theory goes that grass court tennis changed forever on 3 July 1994, when Sampras defeated Ivanišević 7-6 (7-2), 7-6 (7-5), 6-0 in one hour and 55 minutes of spectacularly soporific tennis. In the first set, whose 49 minutes yielded not a single break of serve, the BBC counted five minutes of actual tennis. On a baking hot day in south-west London, the longest rally of the match lasted six shots.

Clearly, the All England Club was not entirely satisfied with the product on offer. This was not the net-rushing artistry of Rod Laver and John McEnroe, or the relentless backcourt mastery of Bjorn Borg and Jimmy Connors. It was a serve bot stamping on a human face — forever (or at least a couple of hours). Something had to give.

Indeed, only weeks earlier Sally Jenkins, the great American sports columnist, had written an article which adorned the front cover of Sports Illustrated, with the provocative but not entirely facetious question: is tennis dying?

The following year, the All England Club introduced a new, lower-pressurised ball. It made little obvious difference — the next six men’s singles titles were won by net rushers. But it was at least evidence that the tournament recognised there was a problem and, critically, demonstrated a willingness to do something about it.

It's Not Easy Bein' Green

On clay, the ball catches dirt, embraces spin and bounces up high. On grass it stays low and shoots through. One other obvious difference is that grass is a living, breathing surface which deteriorates with repeated use. And so by the end of a two-week tournament, entire patches appear bare, leading not just to low but erratic bounces.

So, Wimbledon altered the composition of its grass. Stay with me. For decades, it had been composed of 70 per cent Perennial Ryegrass and 30 per cent Creeping Red Fescue. But for the 2002 tournament, it was replaced with 100 per cent Perennial Ryegrass.

The court certainly plays much more consistently, and also higher — with a relative bounce of 80%, up from 70%. This benefits baseliners and punishes serve-and-volleyers. This alone did not kill serve-and-volley, but sure made it harder to thrive.

A few years ago, I spoke to Neil Stubley, head of horticulture and courts at Wimbledon. In an eerily quiet but reassuringly drizzly Centre Court, he explained:

“If the ball seems like it’s staying low, you’ll have to search for it. Whereas if it’s coming up, you’ve got more time. People say it’s got to be slower, because the ball is coming through to me now… Sometimes it’s player perception.”

Graham Kimpton, head groundsman at Queen’s, was a little more blunt:

“People say ‘they’ slowed the courts down as if there’s some sort of CIA conspiracy. I don’t think anyone specifically went out and said ‘you must slow these courts down’. Like Wimbledon, we were trying to reduce the wear.”

Four-time Wimbledon semi-finalist, Tim Henman, was not convinced. Of a 2002 match against baseliner Andre Sa, he said:

“I’d gone past feeling frustrated, past crying, I was now just laughing. I couldn’t believe how slow these grass courts were playing.”

String theory

But if the newer courts made things tougher, modern strings made them almost impossible. In the mid-1990s, the top players were largely using natural gut. Then, Gustavo Kuerten, a charismatic and talented Brazilian, won the 1997 French Open. His equipment was a game-changer: he sported Luxilon polyester strings. These enabled him to take massive swings, generating vicious amounts of topspin — kryptonite to a serve-and-volleyer.

Speaking in 2006, nine-time Wimbledon singles champion Martina Navratilova laid the blame for the decline in serve and volley squarely on advances in string technology:

“Serve and volley is very difficult because of the rackets and strings, not because the grass is slower ... it’s so easy to get the ball down, dip it, and then you have to volley up.”

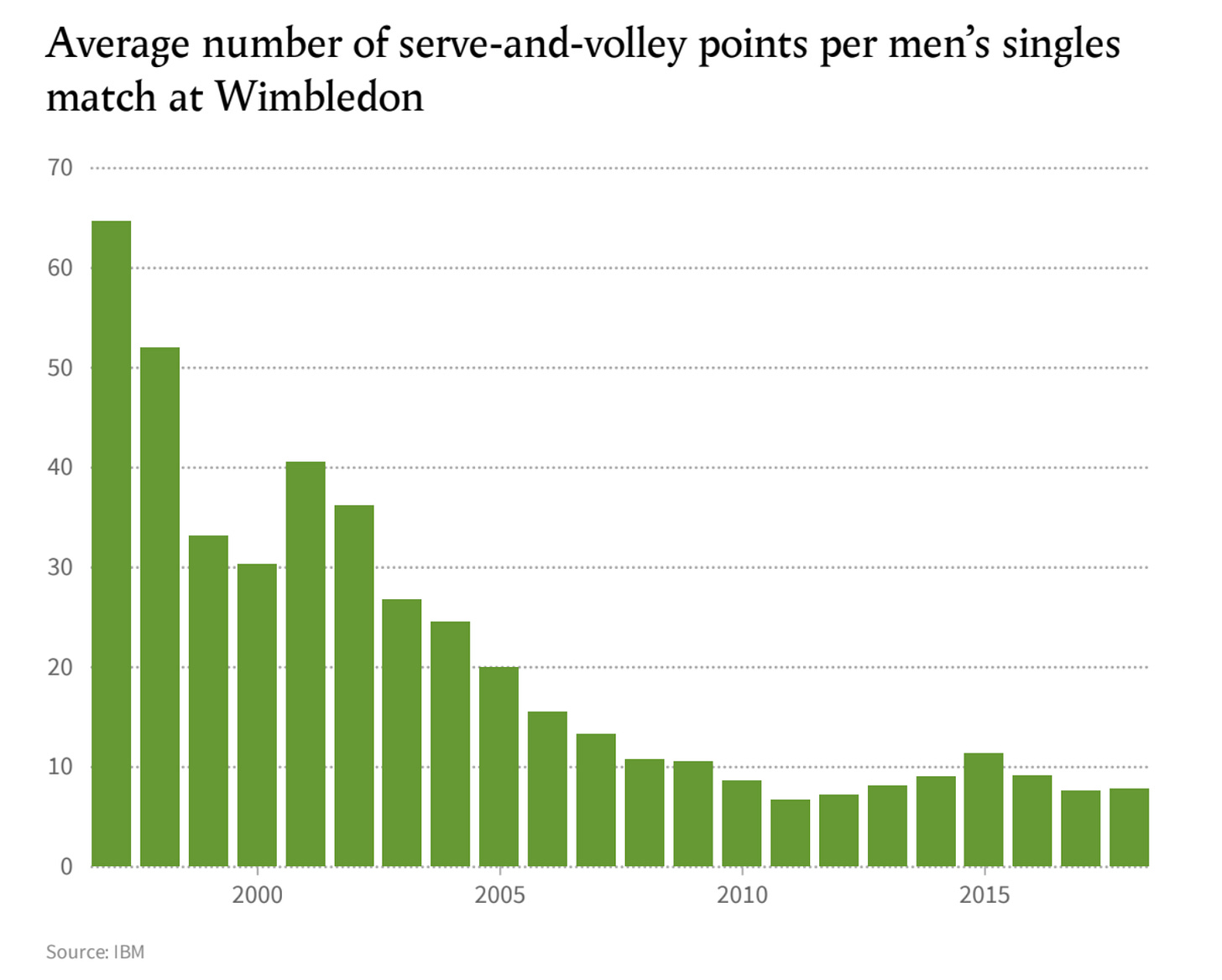

Serve-and-volley did not die all at once or from a single decision by the All England Club. It was chipped away by better strings, larger rackets, slower hard courts as well as the passage of time. Grass remains unlike any other surface. Have you ever played on it? I swear, the ball does not bounce.

But serve-and-volley has been largely relegated to grainy YouTube footage. If you want to blame Goran, go ahead — but it wasn’t one change. Rather, it was a confluence of events that chipped away at the style until it became an anachronism.