ChatGPT is impressive — the margins aren’t

Low interest rates fuelled the last tech boom. This time, AI may have to pay its way

If you took an Uber during much of the past decade, you likely did not pay for the entirety of your journey — shareholders pitched in. In 2018 — the year before the company’s initial public offering — it reported losses1 of more than $3bn on 5.2 billion trips. That means an average loss of 58 cents per ride. Start-ups losing money is nothing new, nor are frothy valuations for tech companies. But the 2010s were unusual for one simple reason: money was practically free.

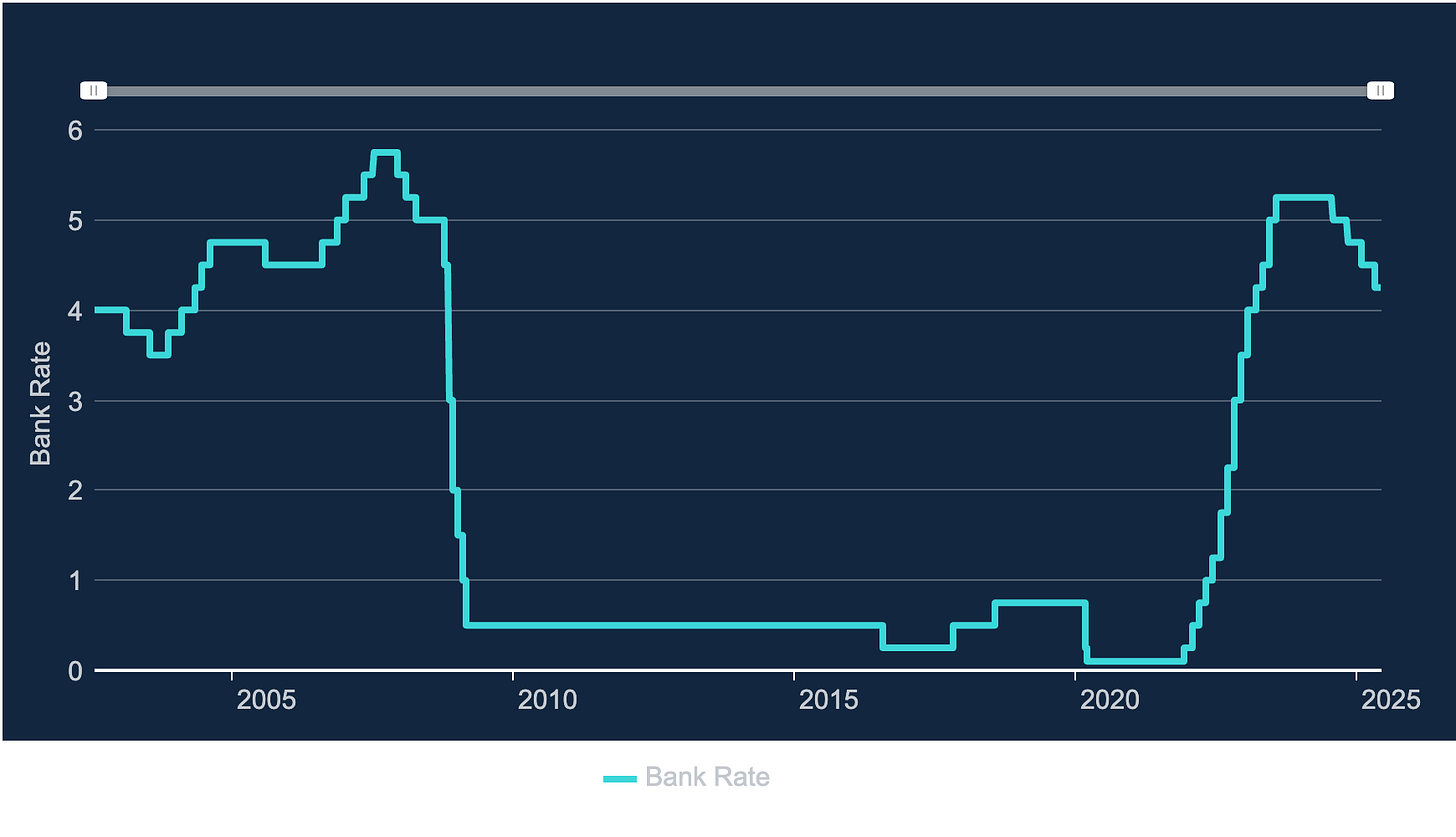

In an effort to combat the global financial crisis and the Great Recession it sparked, central banks around the world slashed interest rates to zero or near zero — the lowest in modern history. And there they stayed for a decade. But what was once historic began to feel normal. Unsurprisingly, weird things started to happen.

Broadly speaking, low interest rates push investors seeking returns into riskier assets. In the 2010s, they were happy to sustain firms with business models that involved losing billions for years in the hope of vast profits in some vague future. Of course, that no longer works when rates return to more traditional levels.

This is the era in which artificial intelligence (AI) firms find themselves. OpenAI, known to the world thanks to its large language model, ChatGPT, is losing lots of money. Last year, the New York Times reported that OpenAI expected to make around $3.7bn in annual sales, yet still lose $5bn. And 2025 is predicted to be worse.

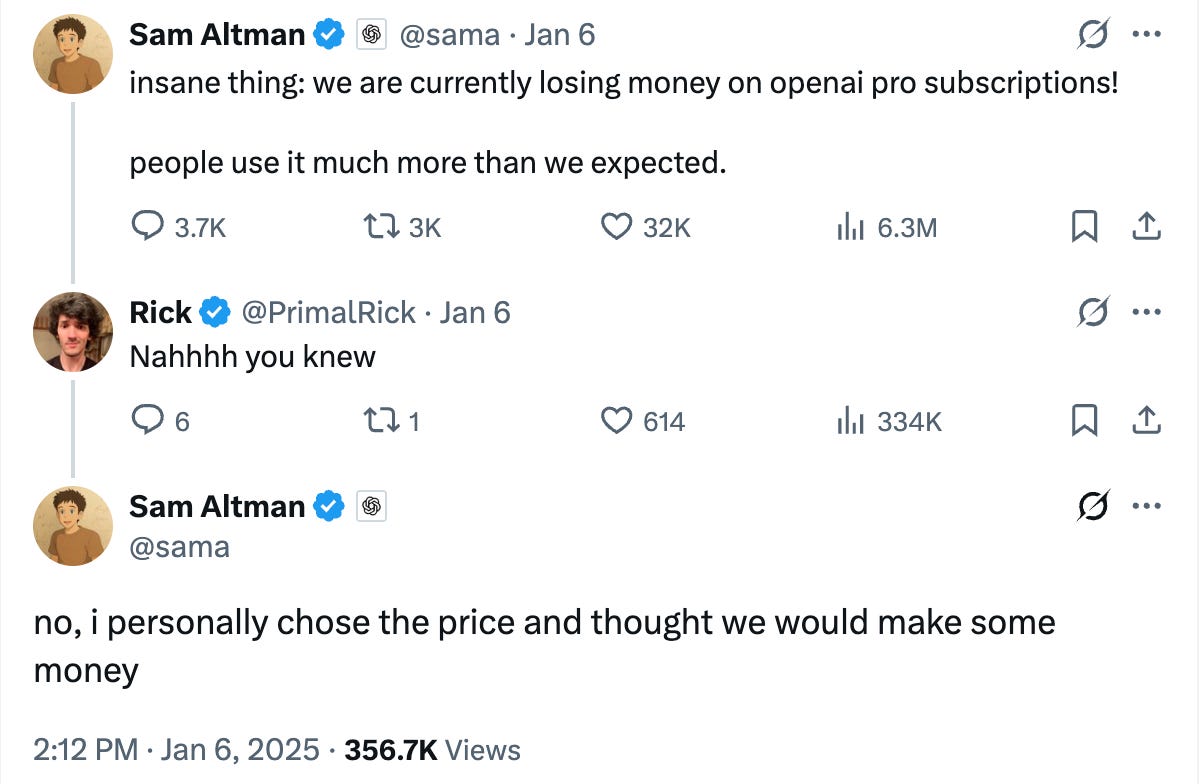

This is perhaps to be expected given that the company is losing money not just for every free user, but even from those with a $200-per-month ChatGPT Pro subscription. OpenAI chief executive, Sam Altman, blamed it on people using the service more than the company expected.

For an expert (and sceptical) view on AI, do check out Ed Zitron’s fantastic newsletter. My interest lies in what the end of the ZIRP (zero interest rates policy) era means for the sector more generally.

Back in the 2010s, tech companies could be confident of spending (and losing) lots of investor cash, all in the name of growing their user base and revenues, waiting for network effects to kick in. Scalability was king — profitability a distant concern. This worked, as long as investors were prepared to eat the upfront costs in pursuit of market dominance and outsized returns at a later date.

In a higher interest world, start-ups of all kinds will face greater pressure from Silicon Valley to achieve profitability. Not only is money more expensive, but investors have other (and far safer) options if they want. With 10-year Treasury yields at around 4.5 per cent, why throw money at loss-making maybes? It is also harder for venture capitalists themselves to raise funds.

This is compounded by the fact that the economics of AI can be brutal. For social media platforms, the marginal cost per added user is negligible. But each query sent to a large language model like ChatGPT requires significant computational power — often involving expensive processors running in data centres that consume vast amounts of energy (and water). Throw in research and development costs and it is not difficult to see the problem.

Perhaps AI companies can optimise for government contracts, especially attractive in a period of rising defence spending. Moreover, governments are usually good for the money, often prepared to pay for partial progress, and are keen to have national champions. But someone is going to have to bear the losses.

For employees, that may mean fewer perks and more layoffs. For customers, higher prices. But for AI firms themselves, it may simply drive a necessity to turn a profit far earlier than their predecessors. A business model based on actually making money — if you came of age in the 2010s, that might feel like a revolutionary concept.

At the time the company made its initial public offering in 2019, which valued the company at $82.4bn, it had never turned a profit