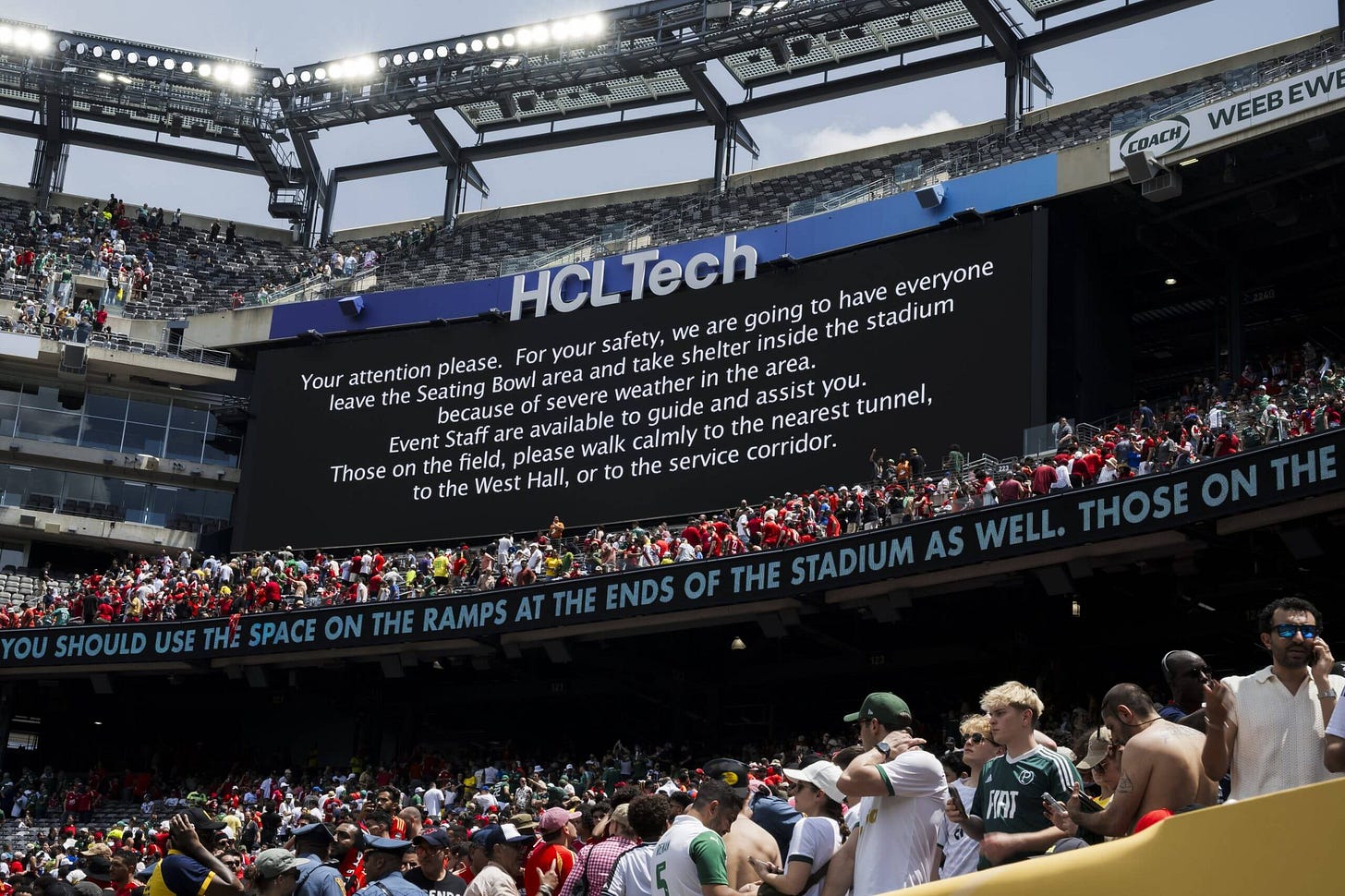

In America, weather isn't small talk

Unlike in Britain, storms kill. When the referee tells you to take cover, you take cover

Like any self-respecting, socially awkward teenage boy, I fell in love with Bill Bryson. My introduction arrived in the form of Notes from a Big Country, a collection of articles originally written for the Mail on Sunday, which followed the author’s struggles to adapt to life in Hanover, New Hampshire, after two decades living in Britain.

Each chapter saw Bryson tackle a new subject, often predicated on his shock at how, well, American the United States had become in his absence. The book is excruciatingly funny, of course, but was also deeply personal to me. After all, I was a Brit who, by accident of birth, was also an American enchanted and baffled in equal measure by US culture.

But the line of Bryson’s I remember most fondly is from his first travel book, The Lost Continent: Travels in Small-Town America. Amid a 14,000-mile jaunt around the country between autumn 1987 and spring 1988, he found time to observe of the British weather:

“Sometimes it rained, but mostly it was just dull, a land without shadows. It was like living in Tupperware.”

I felt seen, validated and frankly understood in the way other people seem to react when they listen to Joni Mitchell records.

But seriously, let’s talk about the weather

In her seminal book, Watching the English, social anthropologist Kate Fox laid out the unconscious, unwritten rules of Englishness, from dress codes to when it is acceptable to acknowledge the existence of other people on public transport (answer: only when your flight is cancelled or the train stops in the middle of a field for more than 15 minutes).

There is, naturally, an entire chapter dedicated to the weather. The point to understand is that when British people discuss the subject, they are rarely swapping views on climatic conditions. “Cold, isn’t it?” Fox notes, is not an invitation to discuss the movement of a cold front. It is just something to agree on. Indeed, the only acceptable response to the above question is “Yes, isn’t it?” followed by a “brrr” if you fancy a flourish.

One curious aspect about the English weather is how little there is of it. Temperatures, at least in the south of England, rarely dip below freezing or above 30°C. Sure, it rains, but does not often flood. Hurricanes are so infrequent that many people will still refer to a Michael Fish forecast from a storm that hit land when The Bee Gees’ You Win Again was top of the charts.

Of course, the sheer moderation of our weather is what usually stands out most. In other countries — even before anthropogenic climate change — going outside can kill you.

Now, let’s talk about football

English football watchers, including the clubs themselves, have been conspicuously surprised by the extremes of American weather during the 2025 FIFA Club World Cup. Chelsea manager Enzo Maresca called it “a joke” after his side was forced to leave the field for almost two hours due to a storm delay1, the sixth such at this year’s tournament.

Of course, there is no such thing as ‘American weather’. The place is massive, and is often experiencing droughts, flooding, snow and heatwaves all at the same time. But there is a good reason why players, officials and fans are told to seek shelter during thunderstorms: it is dangerous.

The US National Weather Service finds that last year, lightning killed 10 people, thunderstorm winds 39, tornadoes 52 and hurricanes 78. There were even 16 deaths attributed to mudslides, which sounds like a particularly gruesome way to go. Hundreds more were injured in these events.

The UK is not immune to weather-related mortality, of course. Indeed, instances related to heat represent a growing danger, with more than 1,300 heat-associated deaths during the four ‘heat episodes’ in the summer of 2024, according to a report published by the Department for Health and Social Care. Still, the worst our footballers are usually subject to is a cold, wet night in Stoke.

There are a few further reasons why the Club World Cup has been so badly affected. First, most major US sports are played either indoors (basketball, ice hockey) or in winter (NFL). Second, many of the matches have taken place in cities where summer storms are common. When it comes to next year’s FIFA World Cup, which the US is jointly hosting alongside Canada and Mexico, the risk of thunderstorm-related delays may be reduced, given that more stadiums have roofs and those on the west coast are less likely to face such conditions.

As an aside, I do wonder how America’s climate of extremes impacts its culture and in particular tolerance for risk. Specifically, if nature can kill you just for going outside, does that make you less worried about being shot by a stranger (or family member) legally carrying an assault rifle?

Not everyone is so lucky as to live under perpetually plasticky, greyish skies. So if you’re in the US and the referee tells you to take cover, you take cover.

FIFA protocols state that if there is lightning within a 10-mile radius of a stadium, matches face an automatic 30-minute suspension.

The forecasting of weather events in the US will now be degraded as a result of the Trump budget cuts to the National Weather Service. Regarding the upcoming World Cup, will be interesting to see how many take the advice of many Democrats who are advising people stay home in light of this administration’s terror campaign against imigration.