How not to answer the question

The subtle art of saying nothing, elegantly

Sometimes, when I’m trying to annoy my other half or just looking to pass the time, I deliberately respond to innocent inquiries in the style of a written parliamentary question (WPQ). It goes something like this:

Question: What’s for dinner?

Answer: Dinner will contain a range of ingredients and further detail will be set out in due course.

Or:

Question: What are your plans for tomorrow?

Answer: I regularly meet with a range of stakeholders to discuss progress on key initiatives.

And most egregious of all:

Question: What time will you be home?

Answer: I remain committed to getting to sleep at a reasonable hour.

Mind your Ps and Qs

Written parliamentary questions are the unglamorous stepsister of oral questions. Instead of standing up in a packed House of Commons chamber to the sound of braying colleagues and the frantic waving of order papers, prepared to ask the prime minister the zinger that will surely lead the BBC News at Six and kickstart your glorious political career, WPQs are generally tabled electronically.

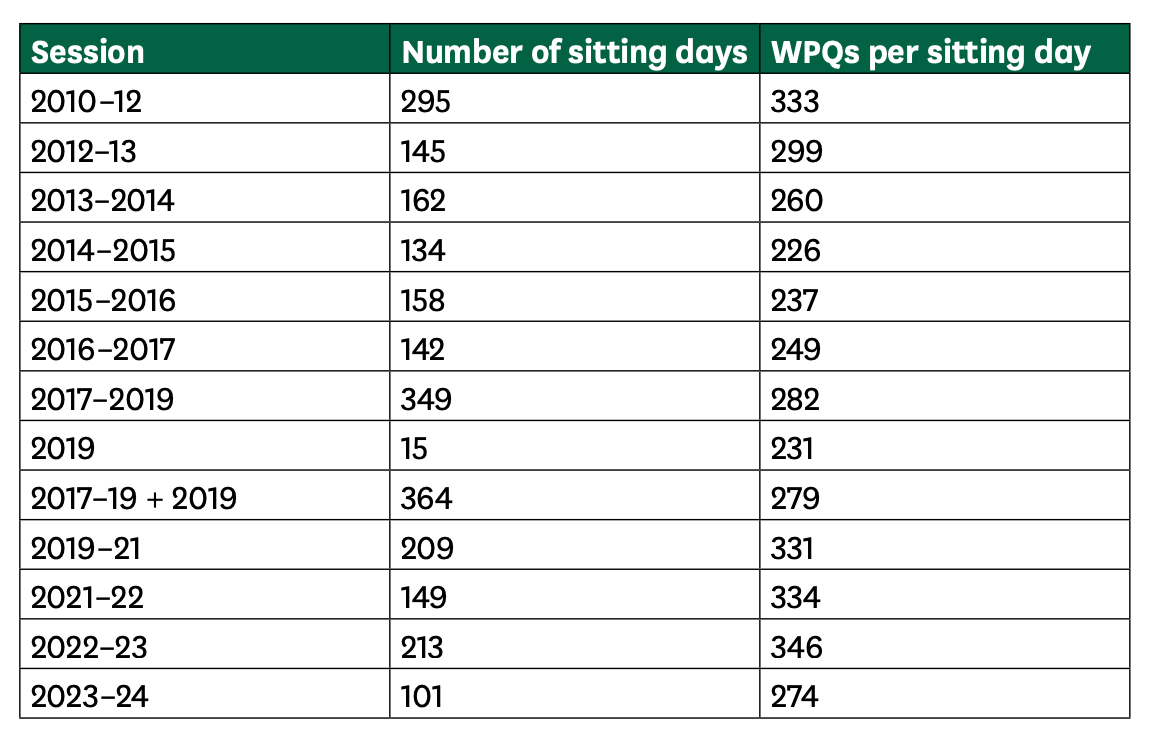

In fact, the vast majority of parliamentary questions arrive in this form. During the 2023-24 session, there was an average of 274 written questions asked per sitting day, many more than the number of oral questions, which are limited by time. And theoretically at least, WPQs can allow for longer and more detailed answers. Rather than an underbriefed minister freelancing on their feet, they are handled by civil servants, often with input from lawyers, specialists and so on.

Of course, there are disadvantages too. As alluded to above, WPQs provide less scope to embarrass the minister. MPs may also be waiting some time for a reply. The cross-Whitehall performance standard is an 85% timely response rate, where responses are deemed ‘on time’ if they are provided within five working days of being tabled. Some departments fare better than others.

I don’t wish to be overly cynical. WPQs can be a useful tool of parliamentary scrutiny and an example of transparency in action. All answers are published online, for the benefit of the media, interest groups and, theoretically I suppose, ordinary citizens. The answers always endeavour to be accurate. A well-timed and sharply-worded question might force the government to release uncomfortable or even unpublished data. But it usually doesn’t.

Sometimes, the issue is, erm, the quality of the question itself. The Table Office, which assists MPs, carefully weeds out those that are not in order or frankly indecipherable. But it cannot hold back the tides. For example, I fondly recall a Welsh MP asking what Barnett consequentials1 would flow to Wales should Heathrow expansion be granted approval. I was tasked with replying that, as the project was funded by the private sector, no such money was due.

Then there are also the questions, usually nearer the end of a parliament, that can charitably be described as time-wasting. In other words, as the government is gearing up for battle, opposition MPs may attempt to occupy as much civil service bandwidth as possible by swamping them with WPQs. Or questions intended to generate more heat than light, such as on the cost of ministerial travel. Your taxes hard at work.

Still, there are occasions in which the government is keen to be as transparent as possible. Of course, it usually arrives in the form of a ‘supportive’ question. For example, when I was at the Treasury, we wanted to get a figure of how much successive freezes to fuel duty had cost the Exchequer2 into the public domain. So a minister approached a ‘friendly’ MP. Given this was during the Brexit wars, there weren’t all that many to choose from.

Of course, if all else fails and you can’t get an answer to your question, you can always submit a Freedom of Information request. At least that gives me 20 working days to decide what’s for dinner.

Housekeeping: Gosh, yesterday’s newsletter was long. Northern Ireland seems to abhor pithiness. Let’s try not to do that again for a while.

The additional funds received by the devolved administrations of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, calculated by the UK Government's Barnett formula

As of today, around £130bn