Does Keir Starmer know who his people are?

To win again, Labour needs to work out what it is for

It was not considered survivable. On 20 January 1972, unemployment in Britain surpassed one million for the first time since the 1930s1. Memories of that decade, and the total war that followed, haunted Conservative and Labour politicians alike. If there was such a thing as the post-war consensus, it was underpinned by a commitment to maintain full employment. This was a moral cause.

But there were other calculations too. It was simply not thought politically possible for any government to win reelection under conditions of high unemployment. Margaret Thatcher put paid to that theory. At the 1983 general election, she secured a majority of 144 with unemployment hovering around three million. In 1987, she won a second landslide, with the figure scarcely lower.

These victories were a result not only of a divided opposition2 and the Falklands War, but because enough voters were doing well enough. Obviously, if you lost your job, life was difficult. But most people didn’t lose their jobs. Meanwhile, inflation – though still high by modern standards – was running well below the 1970s trend. Interest rates were falling, the Right to Buy was in full swing and the economy was growing at a rate that modern day chancellors would die for.

Thatcher also knew who her people were: the self-made, the early-risers, you know, Essex Man, a term coined by Simon Heffer, who defined them as “young, industrious, mildly brutish and culturally barren.” Thatcher nurtured that voter coalition, one which kept her party in power for nearly two decades. Which raises the question: does Keir Starmer know who his people are?

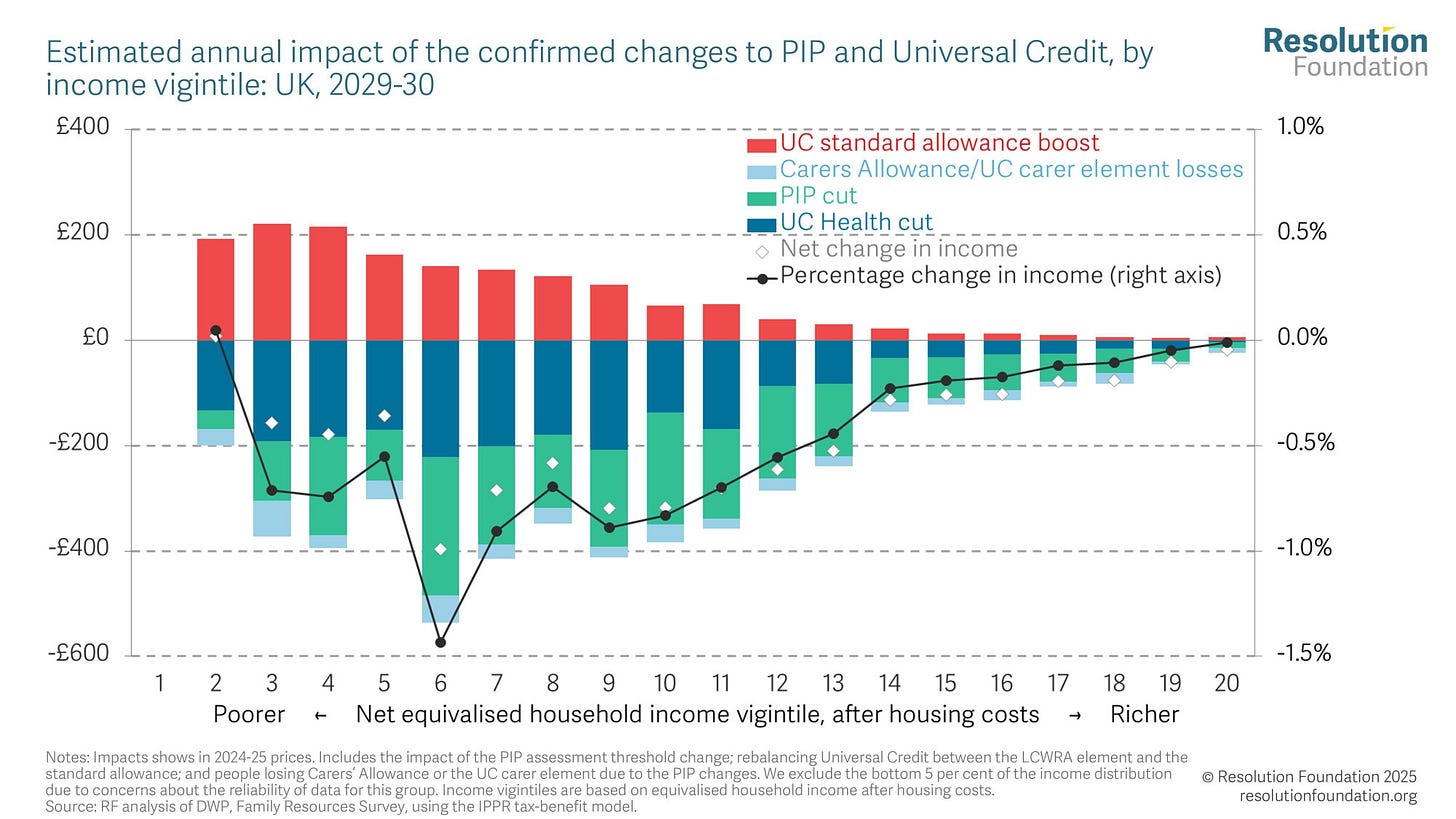

Perhaps it is the poor. Yet Starmer refuses to lift the two-child limit3, while his chancellor just sought to meet her fiscal rules by cutting disability benefits. Analysis from the Resolution Foundation think tank finds that more than two-thirds of the cuts to welfare will fall on the poorest half of the country, with 800,000 people set to lose up to £6,300.

Or, maybe it is young people desperate to get on the housing ladder. But Labour’s promise to build 1.5 million homes in this parliament, always an ambitious target, will not be met. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecasts that 1.3 million homes will be built – from now until the end of the decade. And even that is UK-wide, whereas Labour’s commitment had applied only to England (housing is a devolved competency). Meanwhile, the OBR estimates only 170,000 new homes are due to the government’s reforms to the National Planning Policy Framework.

What about the millions of people waiting – or worried about a loved one waiting – for NHS care? To that end, Rachel Reeves announced a significant spending uplift at last year’s Budget, including £22bn for the health service. But the billions promised are heavily front-loaded, and also imply cuts to unprotected departments such as local government and justice. A party elected in large part thanks to disgust at the state of public services faces real peril if it does not achieve a material improvement.

Or growth! I forgot about growth, which I think might be Labour’s number one priority. Bad news on that front. The OBR has halved its GDP forecast for 2025, in part due to forces outside of the government’s control, not least Donald Trump and tariffs. Tax rises are almost certainly coming in the autumn, though that is unlikely to do much for growth or disposable income, and could negatively impact consumer confidence too.

Real talk. Labour secured a landslide on a 33.7% share at the last election. It lost young, left wing and Muslim voters to the Liberal Democrats, Greens and independent candidates. It will face similar headwinds again, plus a Lib Dem leader in Ed Davey happy to say nasty and truthful things about Trump that Starmer simply cannot endorse. And though Reform UK poses a larger threat to the Tories, it is still more than capable of peeling off Labour voters as well.

Look, it’s easy to criticise (fun, too). And even if Labour did all the right things, and got a bit of luck, it still might not matter. Joe Biden just presided over perhaps the greatest economic recovery in recorded history and didn’t even make it to election day. Professional politics is not a morality tale.

That is how Thatcher was able to win reelection – because unemployment didn’t hurt her people. Labour, for its part, can win again even with a flatlining economy. Or high levels of child poverty. Or overcrowded prisons. But in order to do so, Starmer needs to work out who his people are.

The House of Commons debate two days later was a brutal affair for Ted Heath

Polling analyst Matt Singh argues persuasively that the Labour split and resulting Liberal-SDP Alliance did not hand the Conservatives victory, as is often believed

Institute for Fiscal Studies review into the impact of the two-child benefit cap

Great article.

What hurts people is bills.... water, electricity, gas, broadband, council tax etc all going up well above inflation. What hurts people is not being able to get a GP appointment, or waiting a year for a hospital appointment. What hurts people is not feeling safe.

Starmer's problem is that unless voters notice and feel a positive difference, he will be in trouble, especially when so many core Labour supporters don't believe in him. He is lucky to have such a weak opposition, but there is a long time until the next election.

Well, the one group of people Starmer absolutely will not upset is anti-immigration, anti-EU Labour Leave voters.