Low expectations are a gift to Labour

Yes, the inheritance was bad. Still, even small improvements will feel like progress

In a world of hard racism and atrocity justification, it is something of a throwback: “the soft bigotry of low expectations”. The line was first uttered by then-Texas Governor George W. Bush, and widely attributed to his speechwriter, Michael Gerson. To hear the phrase in its fullest context is to understand that it amounted to more than a soundbite.

Now, Bush was a truly terrible president. In the words of Frank Rich, he kept America safe “provided his presidency began Sept. 12, 2001” and made America prosperous “provided his presidency ended December 2007." His foreign policy was a quagmire, his tax cuts were reckless and his Supreme Court nominees continue to undermine the rule of law and the rights of minorities to this day.

Nevertheless, this speech is worth a read. Addressing the Latin Business Association on the subject of education, Bush said:

It requires a mindset that all children can learn, and no child should be left behind. It does not matter where they live, or how much their parents earn. It does not matter if they grow up in foster care or a two-parent family. These circumstances are challenges, but they are not excuses. I believe that every child can learn the basic skills on which the rest of their life depends. Some say it is unfair to hold disadvantaged children to rigorous standards. I say it is discrimination to require anything less — the soft bigotry of low expectations.

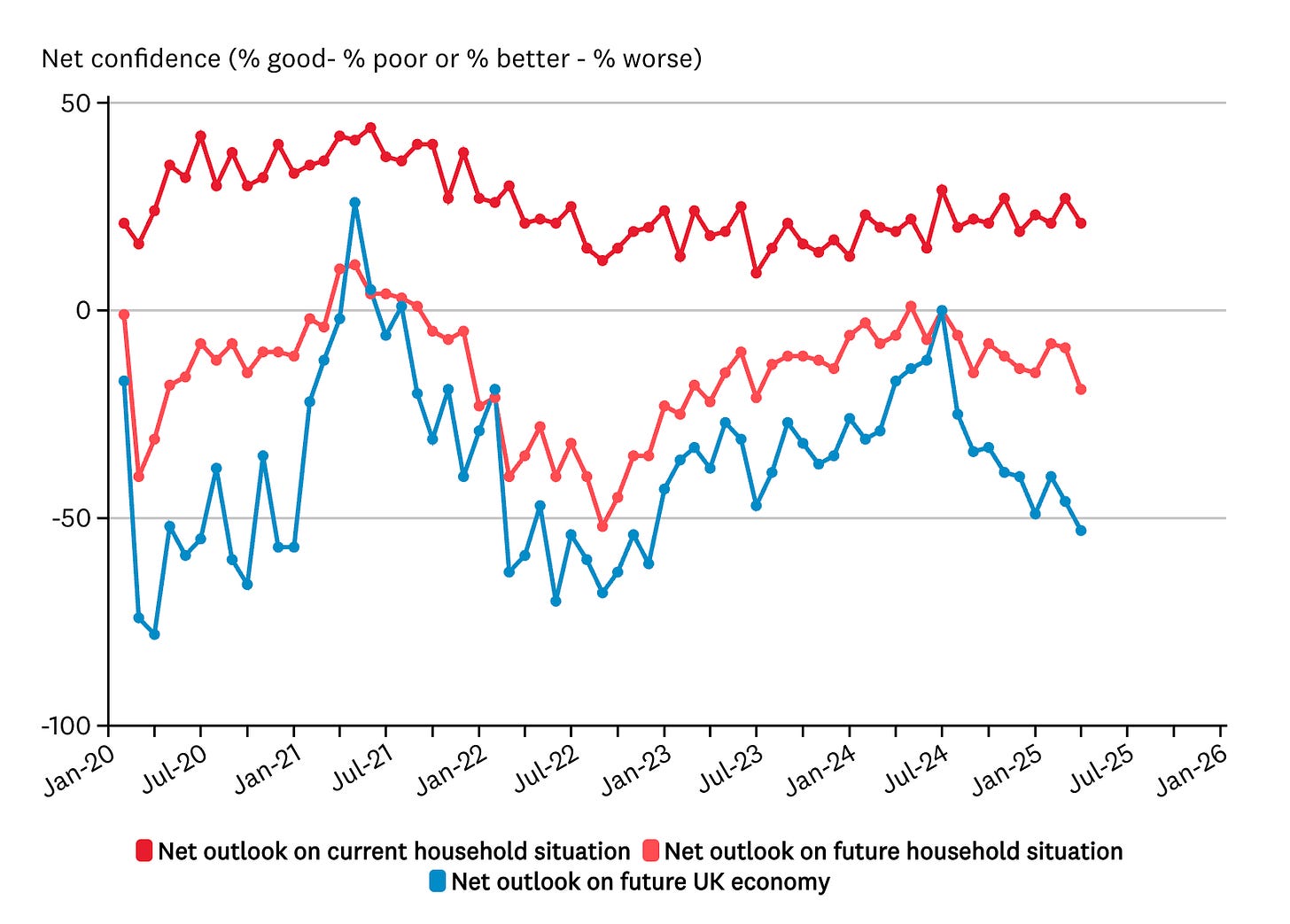

Alright, fun’s over. Time to talk about the state of Britain and specifically, voter sentiment. Consumer confidence fell last month1 to its lowest level since the peak of the cost of living crisis, when inflation was running at double digits. Nearly two-thirds of respondents told the Which? Consumer Insight tracker that they believed the economy would get worse before it got better2.

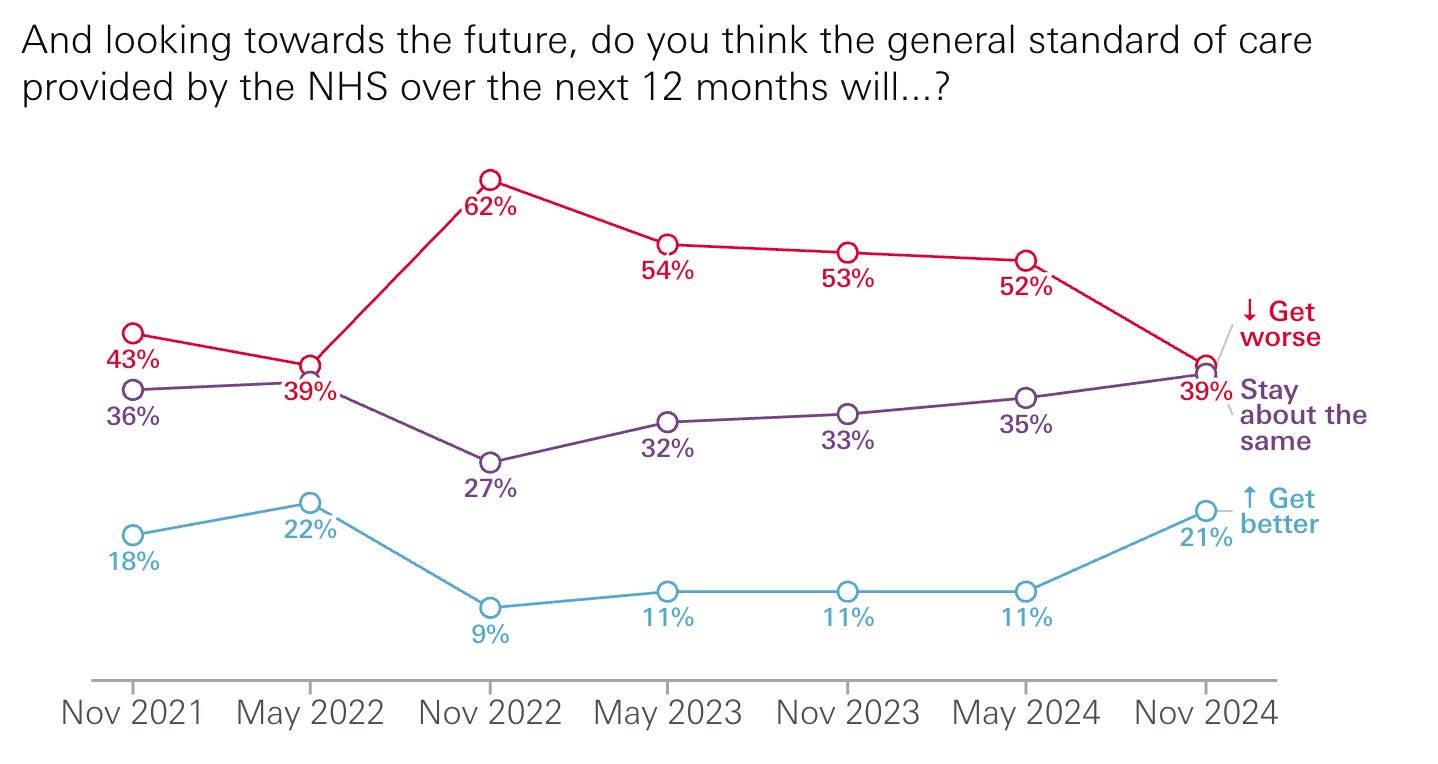

What about public services? A recent study by The Health Foundation and Ipsos found that, when asked about expectations for the general standard of NHS care in the next 12 months, the public is fairly negative, albeit by a smaller margin than a year ago. Results show that 39% think standards will deteriorate while 21% expect they will improve3. With regards to social care, 36% think standards will get worse, and 11% expect them to get better.

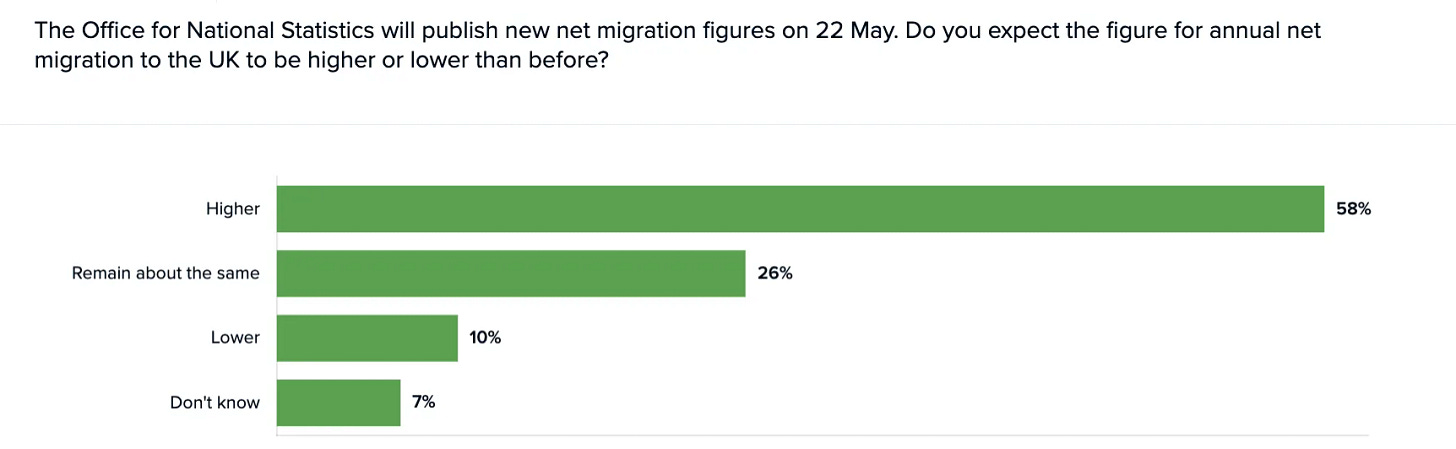

The third example is different to the others, but tells a similar story. Yesterday, the Office for National Statistics revealed that net migration nearly halved last year. This was not a surprise to the Home Office or immigration watchers, given the significant restrictions put in place by the previous Conservative government. It was, however, something of a shock to voters. Research by British Future and Focaldata found that just 10% of Britons were expecting net migration to fall, compared with 58% who expected a rise.

The point is not that Labour has it easy. As the FT’s Stephen Bush notes, its political inheritance was a combination of 1997’s public services and 2010’s economy. (I would add, following the re-election of Donald Trump, the 17th century’s mercantilism.) But such are the low — and in the case of immigration, demonstrably false — expectations of the British public that it really would not take much improvement for something of a feel-good factor to emerge.

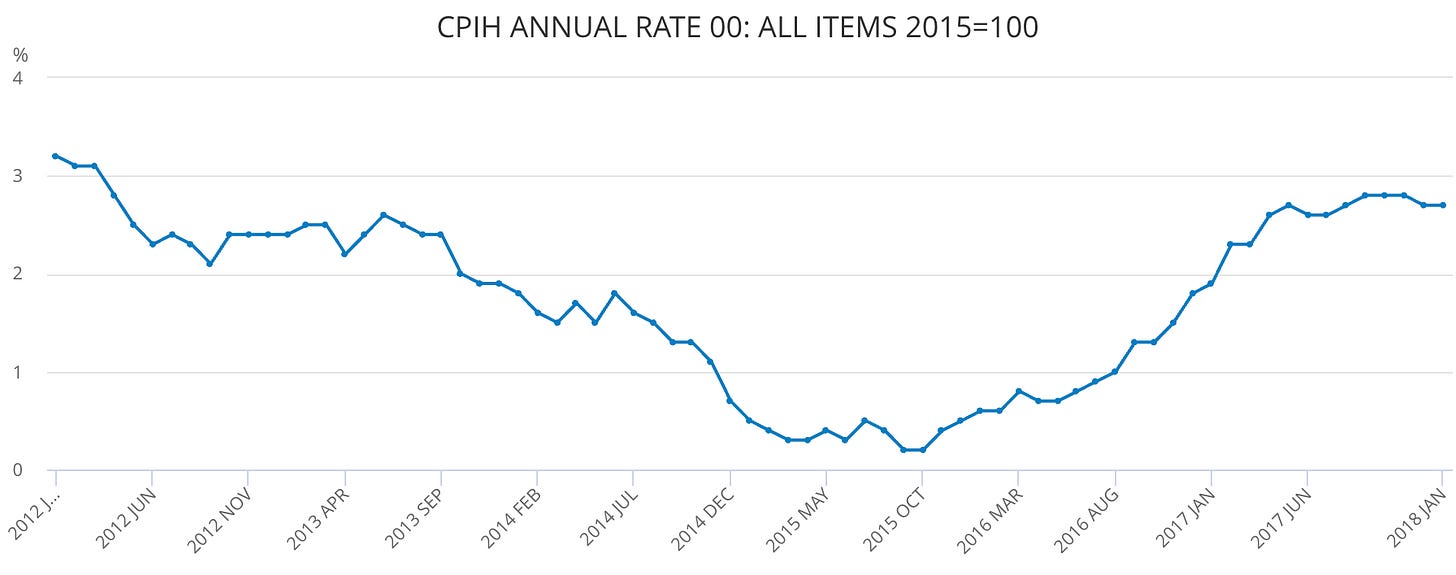

Still sceptical? One big reason why the Conservatives won the 2015 general election is that something unusual happened in the months beforehand: there was real wage growth. The deficit had not been eliminated, unprotected departments had been cut, but with inflation well below 1%, even small rises in pay packets represented rising living standards. Just look at that drop around 2015 — like a sprinter dipping their head at the finish line!

Of course, the Americans were not all that grateful to Joe Biden for presiding over a booming economy. But I don’t believe the British expect US levels of growth or standards of living. I think back to an observation from the great travel writer and all-round Anglophile, Bill Bryson, regarding the striking difference between the marketing of healthcare products in America versus the UK.

An advertisement in Britain for a cold relief capsule, for instance, would promise no more than that it might make you feel a bit better. You would still have a red nose and be in your dressing gown, but you would be smiling again, if wanly.

A commercial for the same product in America would guarantee total, instantaneous relief. An American who took this miracle compound would not only throw off his dressing gown and get back to work at once, he would feel better than he had for years and finish the day having the time of his life at a bowling alley.

If Labour can make the NHS a little better, oversee some gentle economic growth, continue to cut immigration (which may be popular but ultimately make the first two harder!) and preside over some interest rate cuts, it may yet be rewarded at the ballot box.

None of this would amount to a revolution. But in a nation where both wages and expectations have stagnated, even small improvements will feel like progress. In that sense, Labour’s biggest political opportunity may lie not in grand promises, but in quietly exceeding the low bar set by a public that has learned to expect very little.

Worth noting (unhelpfully for today’s thesis but there you go) that the GfK consumer confidence index jumped three points in May, albeit to minus 20. This is the same level it sat in February, but far below the 2015-19 average of minus 5.6.

There are some fairly alarming statistics in the data. For example, Which? estimates that 1.9 million households missed essential payments in April — such as rent or mortgage payments, utility bills, credit card or loan payments.

A year ago, the numbers were 52% to deteriorate, 11% to improve.