Wanted: a normie centre-right party

The Tories' defence of Britain's fiscal watchdog offers a rare encouraging sign

The thing you have to understand about British politics is that the Conservative Party has been rather good at it. The Tories held power for roughly two-thirds of the 20th century, during which they helped win a total war, oversaw an expansion of home ownership, took Britain into the European Economic Community before leading the charge from state-run industry towards a market-based economy.

Such was the party’s dominance that when he stood down in 2001, William Hague became the first Conservative leader not to become prime minister since Austen Chamberlain in the 1920s. Labour, for its part, enjoyed sporadic and frequently troubled interruptions in office, more often threatening to come third in a two-horse race.

In fact, the birth of the Labour Party was among the best things that ever happened to the Tories. Sure, having an avowedly socialist alternative was unnerving, but the Liberal Party had been a far more electorally successful endeavour. Indeed, the Liberals dominated much of the second half of the 19th century, under the leadership of Lord Palmerston and then William Gladstone.

The Conservatives’ success has historically been down to a set of durable strengths:

Ideological flexibility — accepting democratic reform in the 19th century, the post-war welfare state, Thatcherite economics in the 1980s and a more socially liberal posture in the 2010s

Strong appeal to property and stability — in addition to absorbing its opponent’s popular ideas, the party has had a consistent offer of low taxes, property ownership, social order and national continuity

Economic responsibility — even when unpopular, the party often maintained a reputation for economic credibility, administrative competence and safe pair of hands-ism1

Comfort with Britain’s institutions — at its best, the party worked with existing institutions (House of Lords, civil service, judiciary, Church of England) rather than against them, helping to reassure elites and voters wary of rapid change

Effective use of national identity — similar to above, but focused on monarchy, empire, patriotism and, where relevant, war leadership

Benefiting from divided opponents — Liberal splits over Home Rule for Ireland, Labour-Liberal rivalry, creation of the Social Democratic Party2, first-past-the-post rewarding broad, catch-all parties

These strengths help explain why voters have consistently chosen the Tories over Labour. Or, as Tony Blair3 observed in his prediction of the 2015 general election:

“In which a traditional left-wing party competes with a traditional right-wing party, with the traditional result.”

Mel B, Mel C and Mel S

These strengths remain relevant today — as the Tories seek to reestablish their economic credentials. Shadow chancellor Mel Stride is set to deliver a speech at the Institute for Government in which he will defend the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) — an institution that embodies the kind of fiscal prudence and institutional seriousness that historically helped the party earn voter trust.

This intervention is intended as an attack not only on Nigel Farage, who has contemplated abolishing the fiscal watchdog, but also on Liz Truss, who sidelined the OBR ahead of the disastrous ‘mini-Budget’ in 20224.

Stride will say:

“It is not hard to see why a politician like Nigel Farage might want to get rid of the OBR when he fought the last election on a manifesto which made £140bn of fantasy unfunded commitments.”

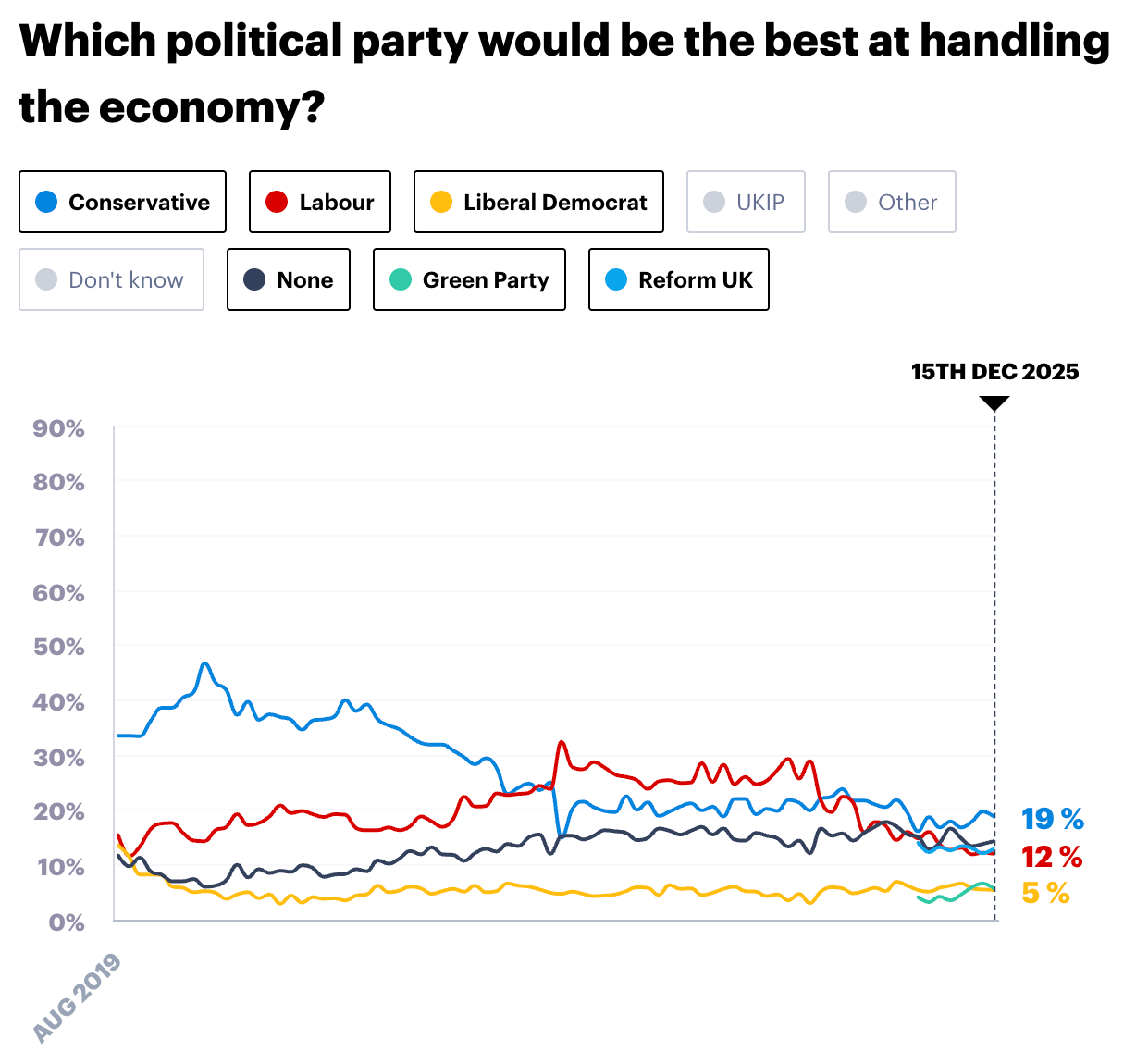

This represents a clear dividing line — and a rare attempt by the Conservatives to play to their strengths on the economy while presenting themselves as a mainstream centre-right party. As you can see from the below chart, the Tories enjoy a narrow lead on the issue.

I know that was then, but it could be again

Unlike during much of their twentieth century heyday, the Conservatives face threats both from without and within. The former is obvious — an insurgent, right-wing, populist party with a charismatic leader. But the call is also very much coming from inside the house5.

Until a couple of months ago, the Tories appeared to have a policy of deporting people living legally in the UK for many years. It still holds a position on Net Zero that would be unpopular with many Reform UK supporters, let alone the former Tories who now vote Liberal Democrat in their droves.

To an extent, the party under Kemi Badenoch feels understandable pressure to compete directly with Reform UK, which has taken not only many of its voters but also former ministers. Yet the Tories still enjoy real strengths on the economy, the nation, and, frankly, being a non-ethnonationalist party that will always place a ceiling on Reform.

Meanwhile, in pure electoral terms, the threat of the Liberal Democrats hoovering up ever more Home Counties seats must surely give CCHQ pause for thought. But this is about more than pure electoral mathematics — it is a question of what the Tory Party is for.

I don’t take a Pollyannaish view of Reform. Recent history tells us that to ignore any Faragist vehicle is a mistake. But there is still definitely scope in the UK party system for a normie centre-right party. One that enthusiastically supports the aspirations of the British people, whether to buy a home, get into university or start a business. One that seeks to assuage the bond markets, build alliances abroad, fight climate change and so on.

This sort of thing may no longer secure the 40% or 50% it did in the second half of the 20th century but, in a multi-party system, it’s not clear it even needs to. I mean, it’s not as if Labour under Keir Starmer is clawing its way to the centre-ground or, indeed anywhere at all.

Would life be easier if Reform UK did not exist, and the Conservatives had no real threat to the right? Sure. But there is still a frankly enormous plot of valuable real estate the Tories can claim as their own and take to the British electorate. Surely the party of the property-owning democracy understands this?

Even in 1997, the Tories led Labour on the economy

Not the reason why Thatcher won in 1983, but still

Hey, there wasn’t a Blair quote yesterday

Stride will also call for the fiscal watchdog to ensure its modelling can “capture the dynamic impacts of policy,” i.e., growth

For another day perhaps, but the centre-right merging or being overtaken by the hard/far right is happening all over Europe and in the US

Curiously enough, Jack, I was thinking about this issue in general and Kemi Badenoch’s **place in history.

We can agree that the Tories will not win the next election. If, by a judicious mix of contrition about the past (her style??) & wise policies going forward, she can stabilise the Tory presence, both in vote share and in seats, such that they may have a shot at power in the mid 2030s, she will deserve a place in history as if she had successfully performed a heart transplant op in her party. But it is a big ask, even for the most successful political party of all..

** I was going to add, “or her successor”, but would yet another leadership challenge produce a better leader? Like Cleverly? BTW, where is he?