Once was enough

If you thought leaving the EU was hard, try rejoining it

Last week, Kemi Badenoch wrote to Pedro Serrano, the EU’s Ambassador to Britain, where she warned that, if elected, the Tories would reverse any offending elements of Keir Starmer’s reset with the bloc. In a letter seen by The Telegraph, Badenoch stated:

“It is important that I stress that the next Conservative government under my leadership would not remain bound by terms that failed the five tests set out above, and damaged the interests of the United Kingdom and its people.”

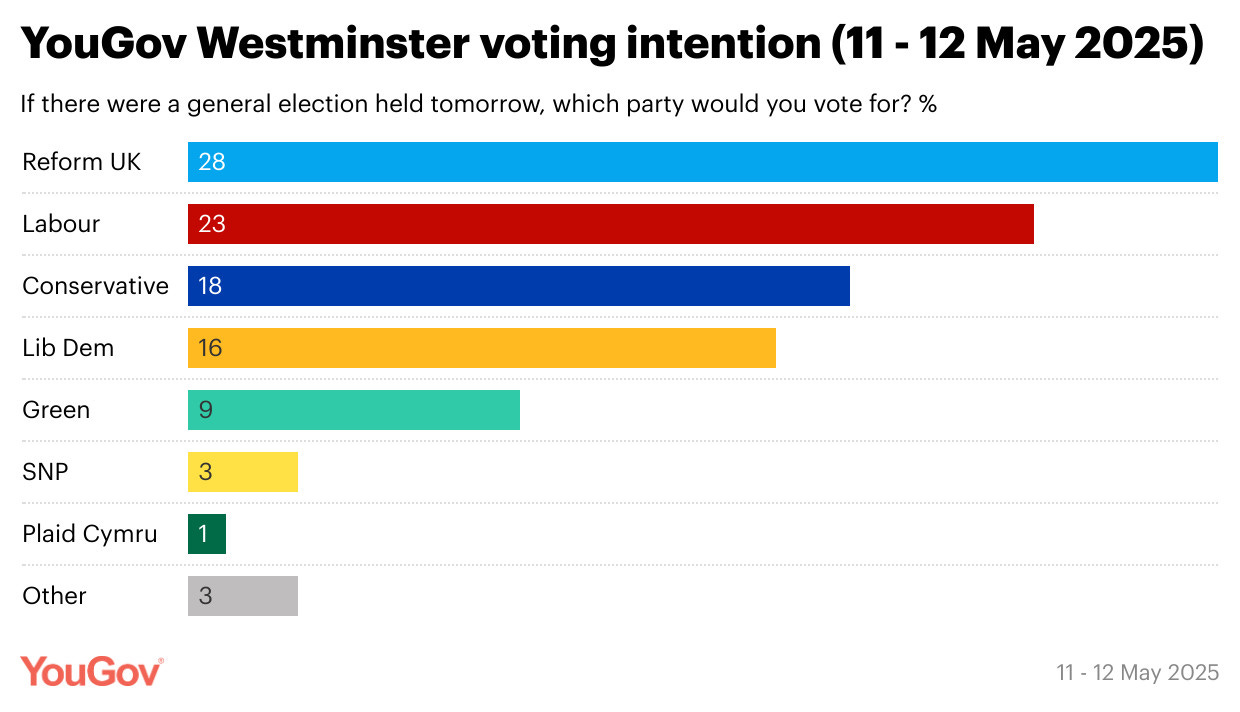

This is not hugely surprising. It is the job of the opposition leader to oppose, the Tories are the party of Brexit, and in Reform UK, they face an even more Eurosceptic1 party streets ahead in the polls. Badenoch is also trying to bolster a narrative that Starmer signs bad deals, citing the Chagos Islands, the US and the recent trade agreement with India.

The question I find more interesting is whether this matters. In the short-term, the answer is clearly not. Labour has a massive parliamentary majority and the prime minister is set to do some sort of deal with the EU, even one that involves dynamic alignment2, something he had previously rejected. Meanwhile, a cursory glance at the polls suggests that the Tories are unlikely to form the next government3. The real issue, therefore, is whether the European Commission takes a longer view.

Any deal Britain agrees to will not be signed by a political party, but a government. To that end, the EU must have confidence that the next one will stick to it, otherwise, why bother? Indeed, this was the problem Theresa May faced when negotiating Brexit — EU leaders reasonably asked themselves what was the point of granting concessions to a prime minister who could get no deal through parliament, while Boris Johnson was waiting in the wings, prepared to unpick any agreement.

That is why cross-party consensus matters, no matter how large or small the parliamentary majority enjoyed by the government of the day. From climate change and industrial policy to the reform of social care, big things that span multiple electoral cycles require broad support. Without it, investors will be reticent to put their money behind, say, new nuclear power stations, while foreign governments will be less willing to do deals.

The era of multi-party politics

England has entered an era of multi-party politics4. Of the big five, three are broadly pro-EU (Labour, Liberal Democrats, Greens) and two firmly against (Conservatives, Reform UK). This makes changes of governments more likely to produce wildly different Europe policies.

It also makes the chances of the UK rejoining the EU even more unlikely. Suspend your disbelief for a moment and say Labour has built some prisons, cleared the NHS backlog and got the economy growing at 2%5. Starmer is elected on a second landslide, with a manifesto commitment to rejoin the EU. It would still matter that the (presumably) second and third-largest parties were implacably hostile to Europe.

One advantage Edward Heath enjoyed when negotiating Britain’s entry into the then Common Market was that Labour was at least split rather than opposed. Indeed, Harold Wilson himself had sought entry in 1967, only to be rebuffed by French president Charles De Gaulle, and a majority of the Parliamentary Labour Party backed ‘Yes’ in the 1975 referendum.

Moreover, if you thought leaving the EU was difficult, try joining it. Article 50 grants the departing member state a ludicrously short period of two years in which to settle up. Article 49, which establishes how a country can join, suffers from the opposite problem. There is no clock. Just ask Turkey, declared a candidate country in 1999.

Then there is the question of what exactly Britain would be rejoining. As an applicant, the country would be in a far weaker position to demand its old rebate, or the opt-out from monetary union, ever-closer union, and Schengen. All this would make a rejoin referendum far harder to win than the original.

But the biggest hurdle remains whether Europe would actually take us back. And the main reason they might decline is not that they don’t want our security, defence and industrial strengths, but that they cannot be sure that the next government would not simply come along and drag Britain out all over again.

Once was more than enough.

Back in the mid-1990s, it meant basically being opposed to monetary union. We have come a long way since then

The principle that parties to a trade agreement maintain equivalent regulatory standards to each other not just now but into the future

It is frankly an open question whether Badenoch will live to fight a general election

Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have been there for some time

I don’t know, perhaps we discovered vast lithium, nickel, cobalt, manganese and graphite deposits in some uninhabited corner of the country

We are a long way from rejoining so patience is required. The country, this blessed isle, this Demi paradise, this jewel set in a silver sea, is undoubtedly suffering a decline in its fortunes, its self confidence, its wealth and, most importantly, in its ability to manage its affairs effectively. Even if Starmer manages to make a good deal with the EU he is faced with the prospect that a future Tory or Reform government would renounce it. The only way it could be made permanent would be to join the Euro Zone, which could take a decade. The idea that we could trust the voters with another referendum is ridiculous, after all the skullduggery that swung the 2016 Referendum.