Step one: stop biting the hand that votes for you

Or, how to turn peasants into Frenchmen

Nation-building often proves a dispiriting endeavour. Founding fathers can draft constitutions, assert the legal monopoly on violence and commission eye-catching flags, but will the locals actually notice? This was a live question the French state faced well into the 19th century, when the country remained something of a patchwork of isolated communities, each with its own culture and, often, a language other than French.

In his seminal book Peasants Into Frenchmen, the historian Eugen Weber examined how these disparate groups with seemingly little in common were gradually integrated into a unified and specifically French nation-state. This transformation occurred through a variety of means.

Universal primary education helped disseminate the French language and republican values. Military conscription brought young rural men into contact with peers from other regions. Improved transportation infrastructure physically connected rural dwellers with urban centres, facilitating the movement of both goods and ideas. And perhaps most significantly, a national media — including newspapers, books and popular culture — played a key role in fostering a shared sense of nationhood.

The point Weber was making is that national identity — in this case, ‘Frenchness’ — is neither natural nor inevitable. Rather, it is a social and political construction, one that required a sustained and deliberate intervention by the French state. And as an admirer of French culture and voracious consumer of its pastries, I must say I’m pleased with the outcome.

The Right To Buy votes

Forget 19th century France — this a lesson for modern political parties: voter coalitions, like nations, don’t just exist. They’re made. Take the Right to Buy, which allowed tenants to purchase their council house at a reduced price. Labour initially proposed the idea and it even made it into the party’s manifesto1 for the 1959 general election — which it lost by a landslide.

By the late 1970s, the issue was back on the agenda. A study commissioned during the Callaghan administration even acknowledged that “for most people, owning one’s house is a basic and natural desire”. But it was Margaret Thatcher who actually made it happen. The aim wasn’t simply to boost homeownership rates, but to turn Labour voters into Tories. Take it from The Lady herself, who in 1981 told Ronald Butt of The Sunday Times: “Economics are the method: the object is to change the soul.”

Of course, the policy had some nasty side-effects. Right To Buy was not accompanied by like-for-like replacements — I mean, why would a local authority pay full whack to build new homes if they are forced to sell them at a discount? This imbalance has contributed both to a general housing shortage as well as a political crisis for the Conservatives.

People in their thirties and forties — who in earlier generations would buy a house and start voting Conservative — are in many cases still living in rental accommodation, and therefore have little to conserve. Later policies such as Help To Buy enabled a lucky few to climb on the housing ladder, but by juicing demand, this served only to further alienate renters.

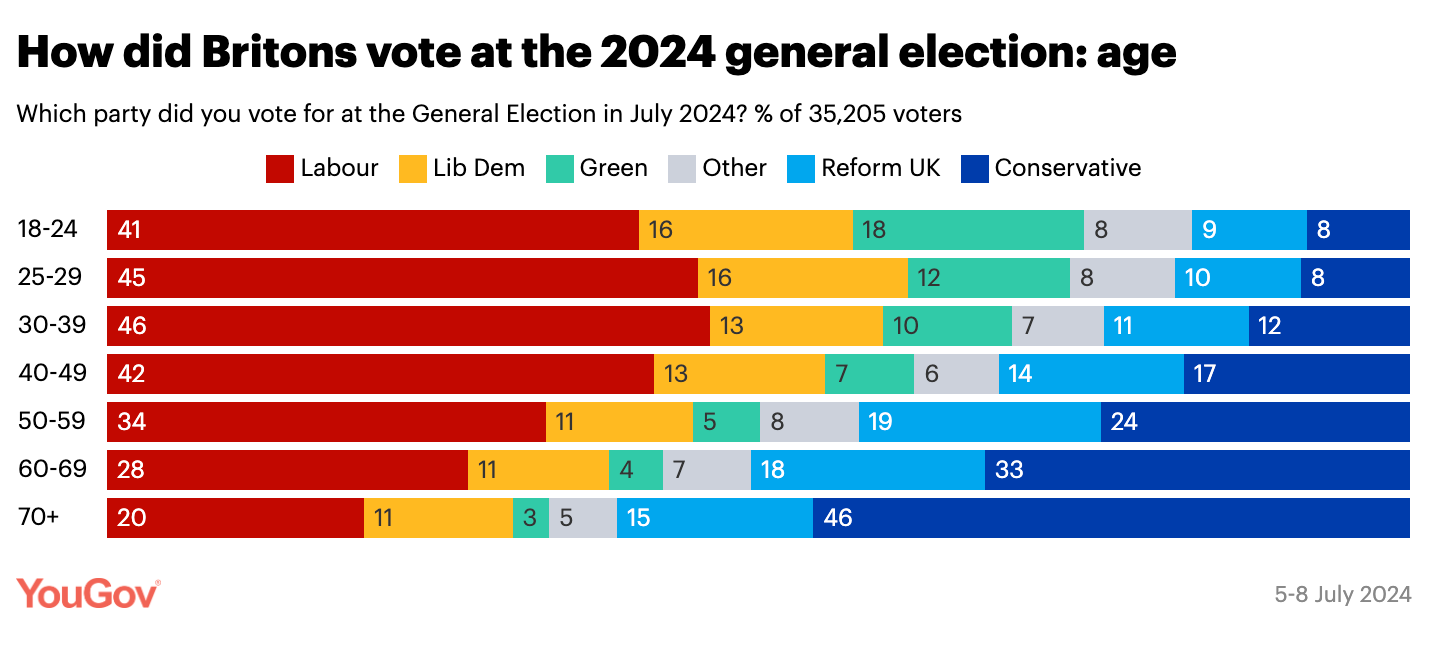

In concert with Tory Nimbyism, the result has been electoral punishment. Polling by YouGov following the 2024 general election shows the youngest age cohort in which more people voted Conservative than Labour was 60-69 years old! I know the Tories lost that election but still. Yikes.

Educating Labour

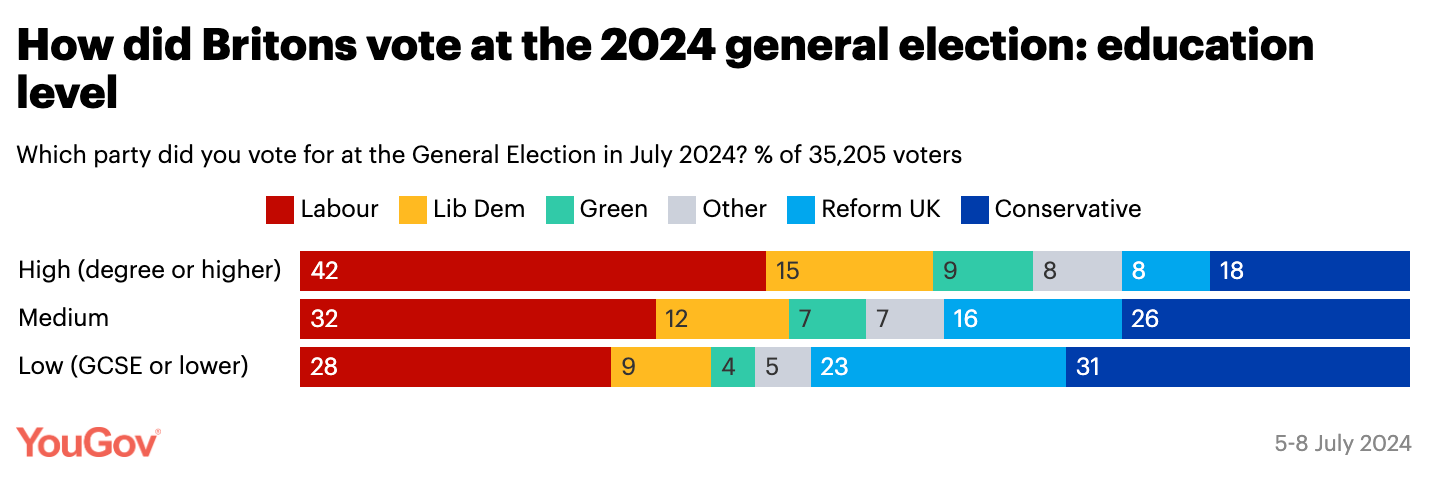

Labour too is more than capable of cutting off its supply of new voters. The same YouGov data finds that the higher the educational attainment, the more likely people are to support Labour. The party secured 42% of voters with a degree or higher, compared with 18% for the Conservatives. You would think, therefore, that cabinet ministers would be schmoozing students and injecting the university sector with capital. But you would be wrong.

At the recent address to investors at an event in London held by Nvidia, the tech giant, Peter Kyle suggested that British students lack “drive” and “vigour”. Things then got weirder. Speaking to LBC’s Nick Ferrari, the business secretary bemoaned the fact that young Brits “Too often people go to university to ‘explore research and knowledge’” when he would rather they got to university “to start businesses in our country.”

In a hopeless attempt at brevity, let’s overlook the fact that research and the pursuit of knowledge are the foundation of what universities do. Or that American students are plenty lazy too. Or that US entrepreneurialism can be as much explained by easy access to venture capital as by work ethic. (Brits are pretty good at inventing things, less good at scaleability etc.)

Kyle — one of Labour’s better communicators — comes remarkably close to slapping his own voters. And sure, the party cannot win elections on the back of graduates alone, but they are a highly motivated cohort2, often geographically concentrated, and good luck even forming a coalition with the Liberal Democrats in 2029 without them.

More broadly, British universities are not in a good way. There were nearly 4,000 redundancies across the sector in 2024 alone and several thousand have already been announced this year, according to a grim tracker from Times Higher Education.

Of course, relentlessly buying voters off can be fiscally irresponsible (see: Hunt, Jeremy) and may not guarantee long-term electoral success. But actively attacking your base when you’re polling in the twenties is bold. More of this and Labour won’t be turning voters into peasants — just Greens.

Housekeeping: I’d love your feedback. This short, anonymous survey (one minute) will help me improve Lines To Take and shape what comes next. Whether you read every issue or just now and then — your thoughts really matter.

Are you really going to read Labour’s 1959 manifesto?

Turnout disparity between graduates and non-graduates was 11 percentage points, according to IPPR

1 - yes, or at least a quick look - your footnotes ARE important ;-)