Working harder, not smarter

20 years of weak productivity growth has left the UK economy running on fumes

Mention the economist Paul Krugman and you usually get one of two quotes. Which the author chooses says a lot about whether they approve or disapprove of the Nobel laureate. For the haters, this 1998 prediction makes for easy pickings:

By 2005 or so, it will become clear that the Internet’s impact on the economy has been no greater than the fax machine’s1.

For the admirers, of which I am one, it is:

Productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run it is almost everything.

The reason, Krugman goes on to explain, is that a nation’s ability to improve its standard of living over time “depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker.” This is a task the UK has heroically failed at going on for two decades, to the detriment of *gestures vaguely* pretty much everything2.

I predict a riot

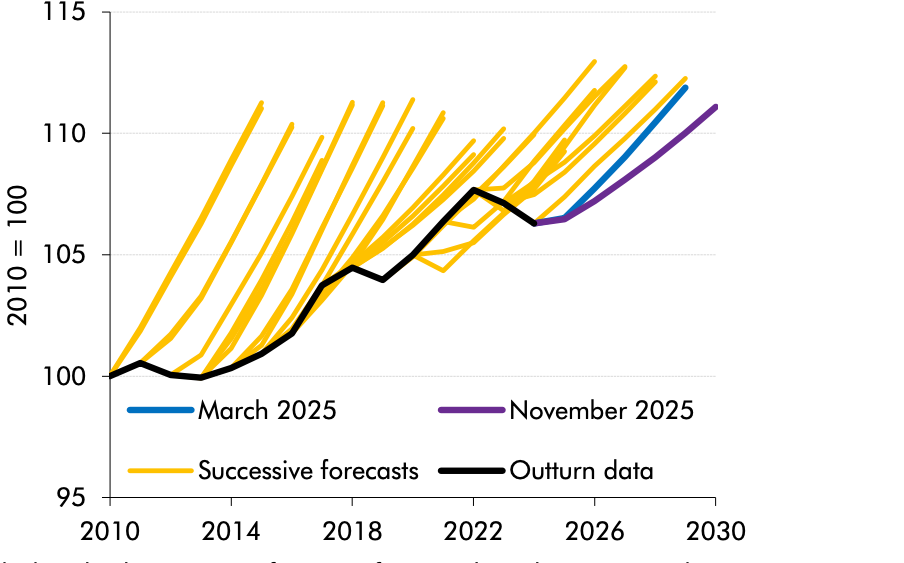

Last month, the Office for Budget Responsibility (or, as whoever ghosted Keir Starmer’s new Substack put it, the Office of Budget Responsibility) downgraded its forecast for underlying productivity growth from 1.3% to 1%. This was, unfortunately, a bit of a big deal, and the Labour government was understandably miffed that the OBR decided to do it on their watch.

But then again, this is a little like getting annoyed at the weather forecaster for predicting winds and rain. It’s autumn and you live in London! And more to the point, the 0.3 percentage point revision, while significant, is not as large as the 0.5 point revision the OBR made in November 2017 under a Conservative government. And it merely takes OBR forecasts closer to external forecasters, who have been generally (and rightly) less optimistic.

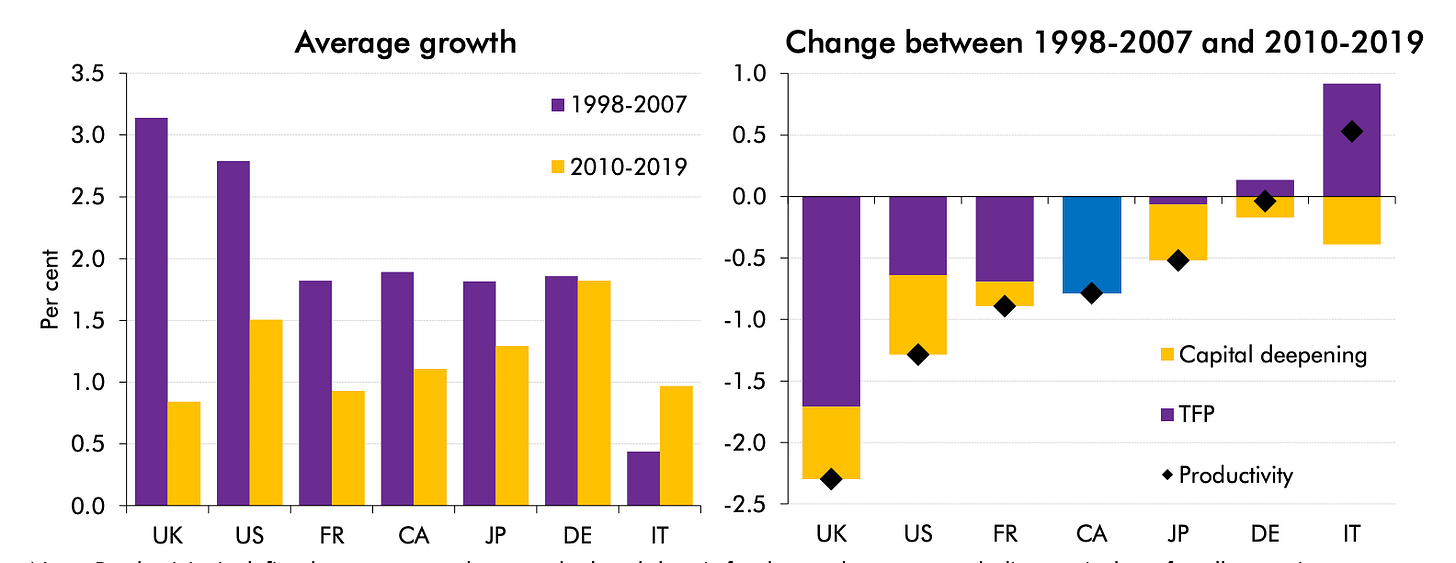

If you subscribe to this newsletter, you are probably 1. conventionally attractive and 2. aware that the UK economy has experienced significantly lower growth in productivity since 2008. But it’s actually worse than you think. In the decade prior to the financial crisis (1998 to 2007 or, as I like to call it, the Arsène Wenger glory years) productivity growth averaged 2.1%. In the decade after (2010 to 2019) it collapsed to 0.6% and since 2020 has fallen further still to 0.4%.

The $3 trillion question is: why, and why now?

Shocks are an obvious starting point. That is what the 2008 crisis was. But usually, as the OBR notes in its report, these are “followed by some reversion to that era’s productivity trajectory.” This never happened. Instead, the British economy has been buffeted by what has felt like successive shocks. The uncertainty unleashed by the 2016 Brexit referendum, the actual (and terribly thin) 2020 Trade and Cooperation Agreement with the EU, the pandemic and Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

As to why now, the Covid-19 and energy price shocks are largely behind us and yet productivity growth has continued to be weak, meaning the OBR felt it had little choice but to conclude that the usual and rapid bounce back witnessed following previous shocks was simply not going to materialise.

But seriously, why?

So, if productivity recovered following previous shocks, why not this time? Initially, it was thought that a combination of labour hoarding, the continued survival of ‘zombie firms’ supported by low interest rates and economic scarring were to blame. But the OBR notes that these temporary factors cannot account for such a prolonged weakness.

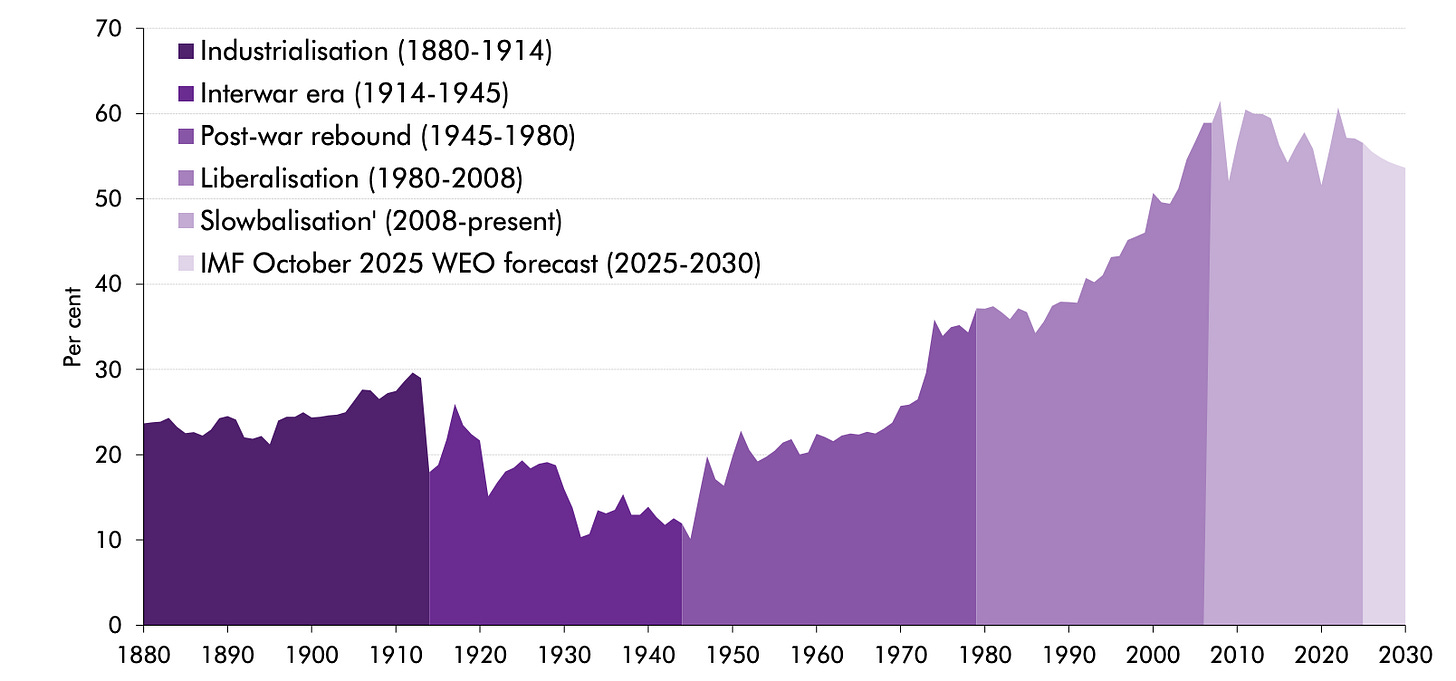

Instead, it has some other ideas. The first relates to trade as a share of GDP, also known as trade intensity. This rose in the 1990s and 2000s, but UK and global trade intensity are forecast to fall in the next few years, a consequence of both Brexit3 and rising protectionism around the world.

Second are various structural shifts within the British economy. The report highlights a slowdown in productivity growth from the financial, manufacturing and information and communications technologies (ICT) sectors since the mid-2000s, which is unlikely to be fully offset by rising growth in other industries.

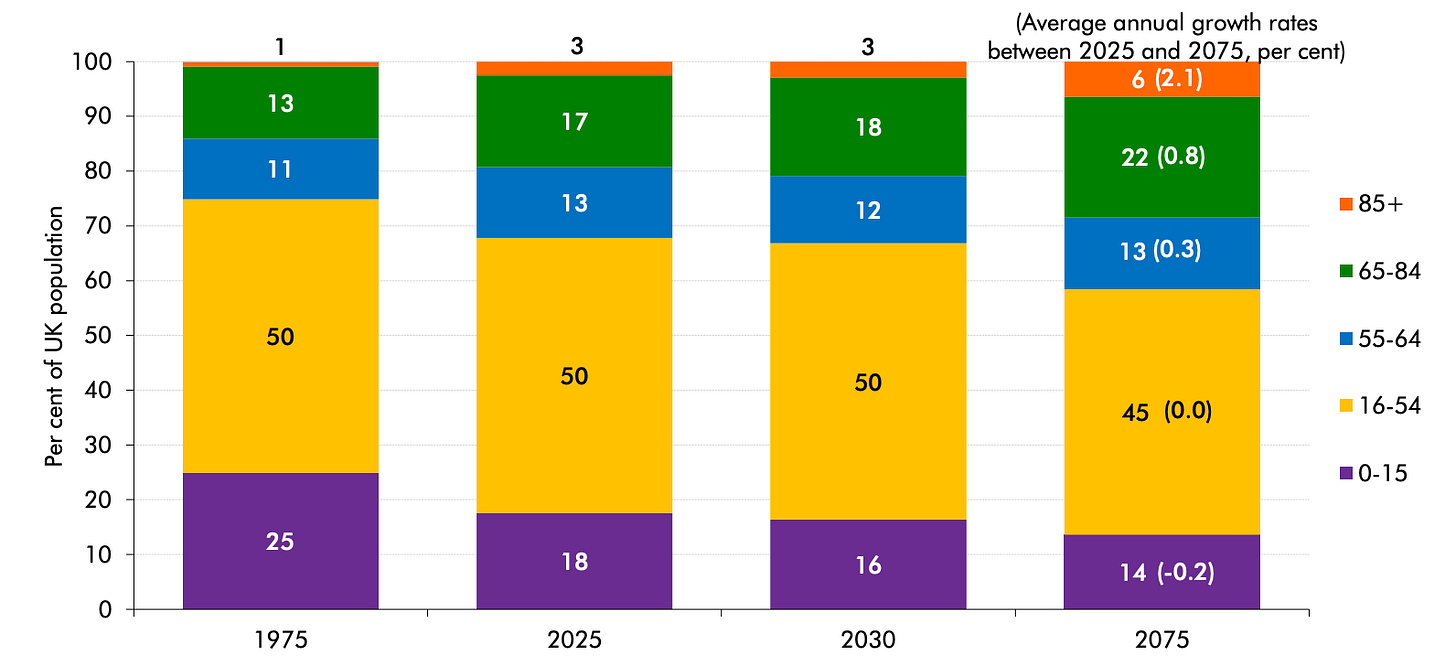

Third is a series of underlying trends. An ageing population is forecast to raise employment in health and social care sectors, which have lower levels of productivity. Additionally, the OBR thinks that artificial intelligence (AI) will have a smaller effect on productivity growth — at least over the next five years — than ICT did before the financial crisis. Finally, climate change may have major negative impacts on productivity growth, what with the loss of a habitable planet and all.

Fourth is long-term underinvestment by UK firms (and indeed the UK government since 2010). For instance, public sector net investment fell from 2.9% of GDP in 2009-10 to 1.6% in 2015-16.

It wasn’t always like this

If Taylor Swift can carve up her musical career into eras, then so too can the UK economy.

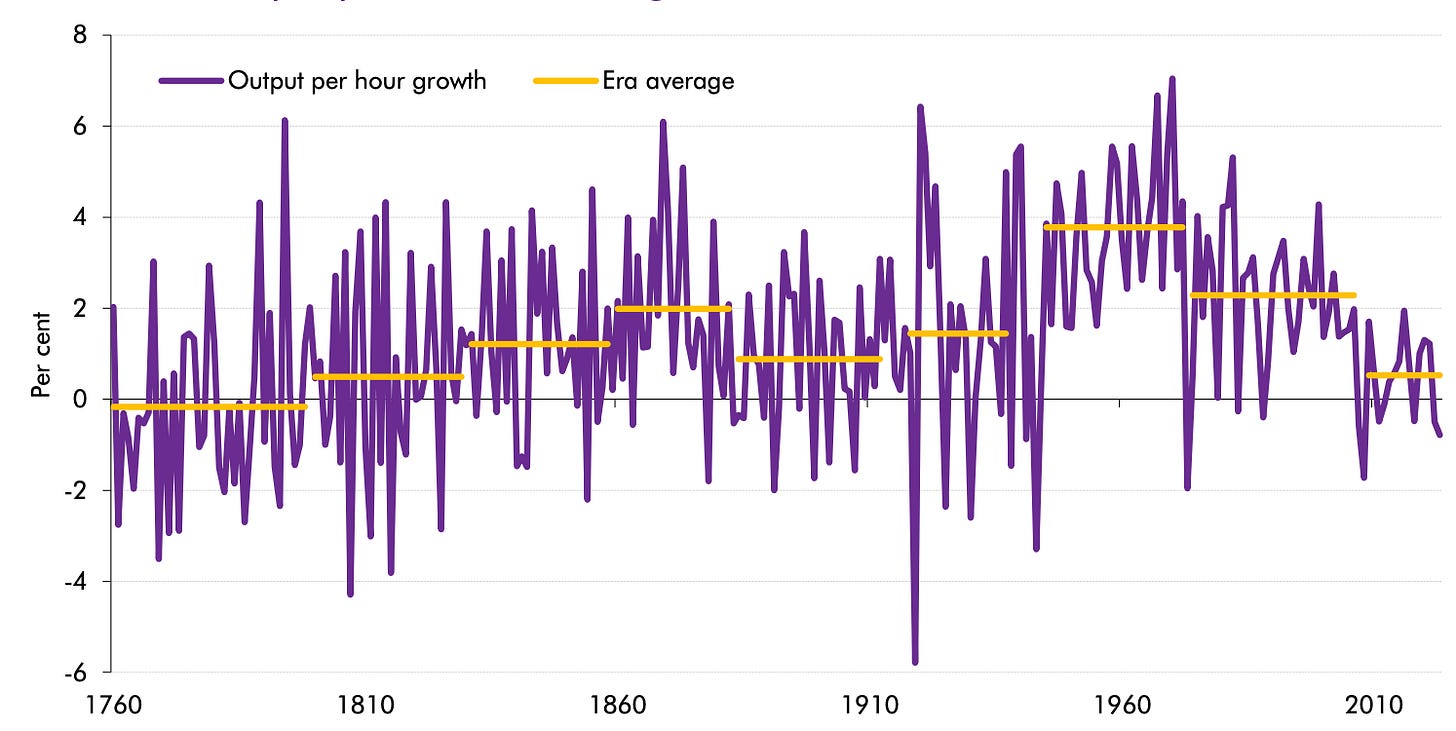

And the above chart is pretty stark. As you can see, there was virtually no productivity growth from the 1760s until around 1800. Then, between 1800 and 1830, growth rose to ½% a year, almost 1¼% until 1860 and then 2% a year from 1860 into the 1880s. What happened? The Industrial Revolution, with its technological innovations, particularly the widespread adoption of steam power in manufacturing and transportation.

Following a few depression and world war-related slumps, the UK economy enjoyed a “golden age” of productivity growth between 1946 and the early 1970s, when output per worker growth averaged a remarkable 3¾%, driven in large part by electrification, the internal combustion engine and chemicals which supported mass production techniques, and later the widespread adoption of computers, broadband internet and wireless mobile technologies.

Fog in Channel; Continent Cut Off

How is the other 98% of the global economy getting on? Short answer — badly but better than Britain. While average annual productivity growth in the UK fell by 2.3 percentage points during the 10 years before and after the financial crisis, the average fall among the other G7 countries was 0.5 percentage points. Consequently, the UK went from having the fastest productivity growth in the G7 to the slowest.

Reasons to be cheerful

The UK has tangible strengths on which a more productive economy could be built. R&D spending underpins world-leading life sciences and universities. We are the world’s third-largest AI market. And still excel in financial and professional services, as well as the creative industries.

What’s missing is a credible plan to back it4 — that is, to double down on these sectors instead of tripping them up with Budget theatre, mixed messages and the occasional bout of self-sabotage (see: universities policy, skilled visa fees, industrial energy prices).

Because the UK isn’t short of talent or ideas. What it lacks is follow-through. Get that right, and we might just surprise ourselves, and get richer in the process.

Krugman explained his thinking to Business Insider many years later

The OBR forecasts that household disposable income per person will fall to around 0.25% a year over the forecast, weaker than the previous decade’s average of 1% a year

The OBR hasn’t changed its assessment that Brexit will reduce UK productivity by roughly 4% after 15 years

To be fair, at 2025 the Spending Review, the government committed £22.6bn to R&D in 2029-30, representing a 13 per cent real-terms increase compared to 2022-23

It’s alway good to have a broad historical perspective on such issues. I have always thought that a combo of both the financial crisis and the effects of Covid constituted, in economic terms, for this country at least, WWIII. But I don’t think many buy that. What I do wonder is whether, compared to, say, the immediate post WWII era, debt markets are more intolerant of what they perceive as national indebtedness. This would or might constrain a more investment-led strategy to improve productivity. But it is clear from your statistical evidence that we are not alone…….

My gut agrees, Jack. The 'dark, satanic mills' and their like undoubtedly improved both productivity and GDP - if anyone then knew what that was. Who knows...? Today AI may yet prove to have the same effect. However, measures of both productivity and GDP are notoriously flawed; some say to the point of being almost meaningless. Apart from that, one is tempted to ask: 'So what?' Is economic growth such a 'good thing'? That's why I so applaud Kate Raworth's Doughnut Economics. Life, national or personal, is a whole of many parts, of which the economy is just one. As an economist and an experienced observer of these things (neither of which am I!) it would be great to know your views. Thanks again for your writing. Brian

.