Reeves isn't Truss. That may not be enough

Even sensible chancellors can lose market confidence

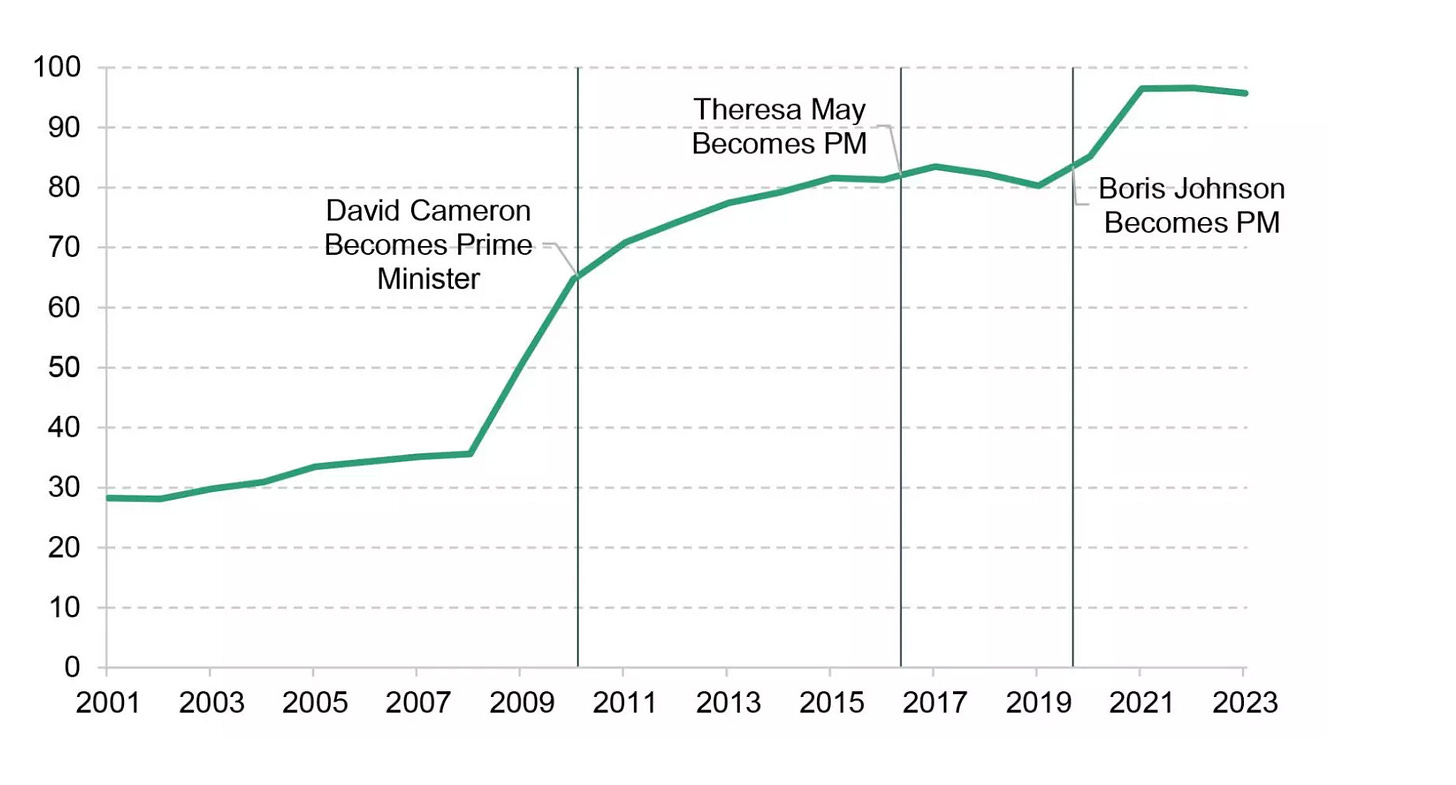

The politics of austerity may be dead, but the economics of constraint is alive, well and doing 20 minutes of planks a day. Cast your eyes back to the fiscal consolidation of the early 2010s. Following the Global Financial Crisis, UK government borrowing surged to more than 10% of national income, the highest level since the Second World War. Debt rose from 35% to 65% of GDP between 2007 and 2009 and, as the Institute for Fiscal Studies notes, was forecast to still be rising in 2016!

Though Labour’s plans would have reduced the deficit more slowly than the Conservatives, there was widespread agreement that the public finances were on an unsustainable footing. Whoever won the 2010 election, there would have been some form of austerity. The biggest difference would have been the flavour.

The June 2010 Budget set out the coalition government’s deficit reduction plan, with an emphasis on spending cuts rather than tax increases at a ratio of 80:20. By 2015, the balance had tilted even further toward cuts. This was, of course, a political choice, one Rachel Reeves is now grappling with.

Almost every day there is a new rumour circulating about which taxes may rise at the Budget. Inheritance tax, bank levies, housing taxes, pensions raids — it is a busy time to be a financial advisor. But we hear much less about spending cuts — and for good reason.

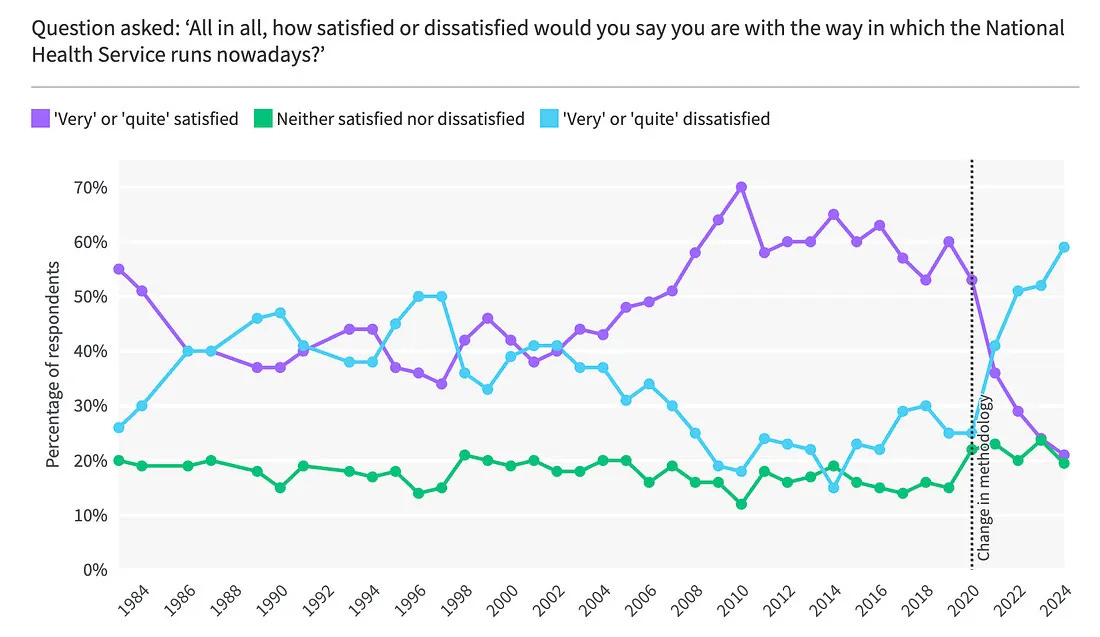

First, Reeves is a member of the Labour Party. Second, when she recently tried to secure a few billion pounds in savings from welfare, the government had to backtrack under such duress it may in fact have ended up costing more money. And third, have you seen the state of the public services? Public satisfaction with the NHS has fallen to its lowest level on record and the prisons are so full we’re letting people out early.

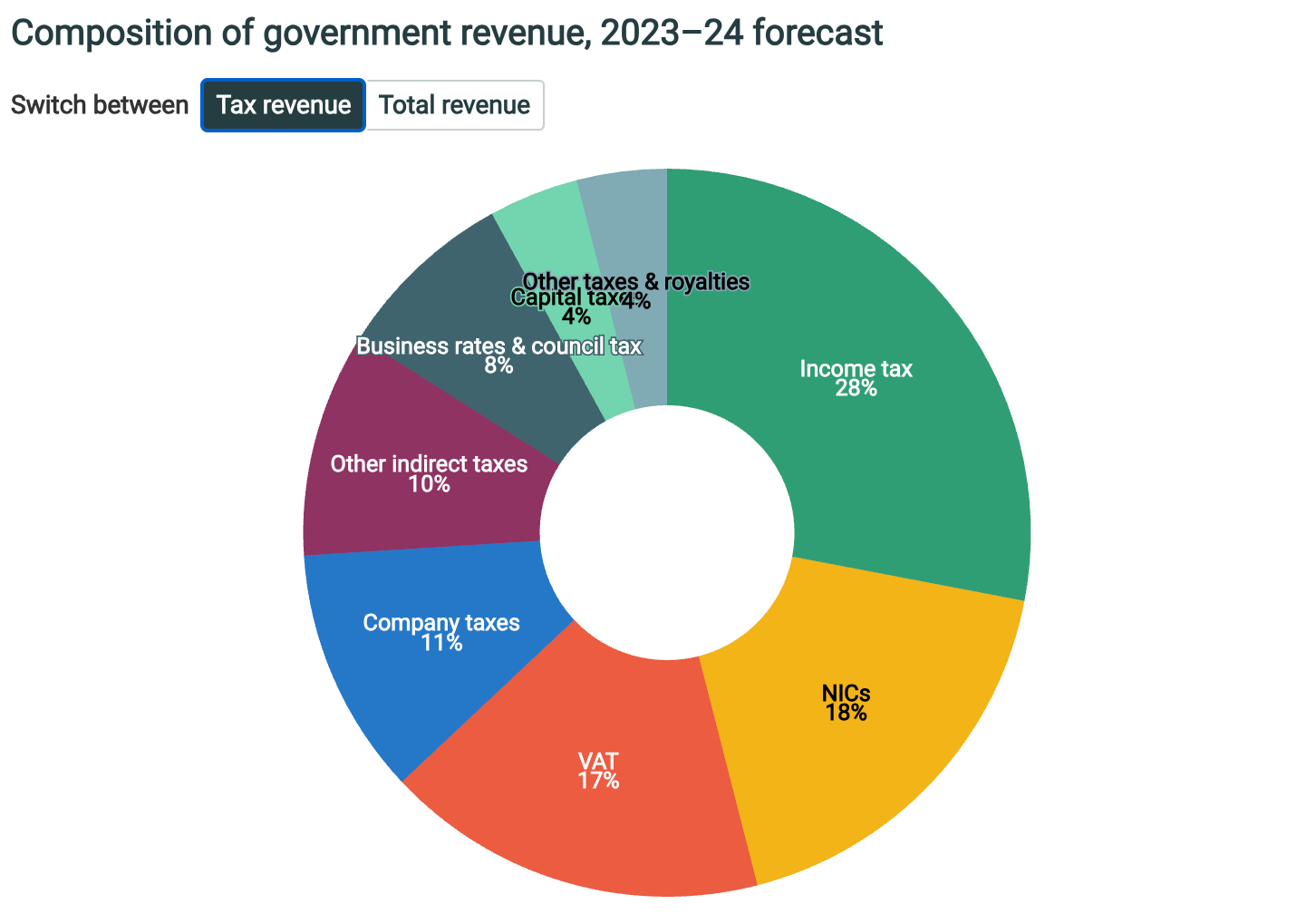

But there’s a problem. Several, in fact. First, Reeves is sticking to her pledge not to raise taxes on ‘working people’, shorthand for income tax, VAT and [employee] national insurance. That is, the three largest sources of revenue. Second, following the welfare reform U-turn, she needs to find another £5-6bn by 2029-30. And third, the cost of borrowing continues to rise.

The yield on 30-year gilts has risen to the highest level since 1998. Meanwhile, 10-year yields, though below the spikes experienced earlier in the year, are still the dearest in the G-7. Why? Well, inflation remains elevated, and so interest rate expectations are too. Moreover, around a quarter of gilts are index-linked, meaning that the interest payments and the overall loan amount are automatically adjusted for inflation.

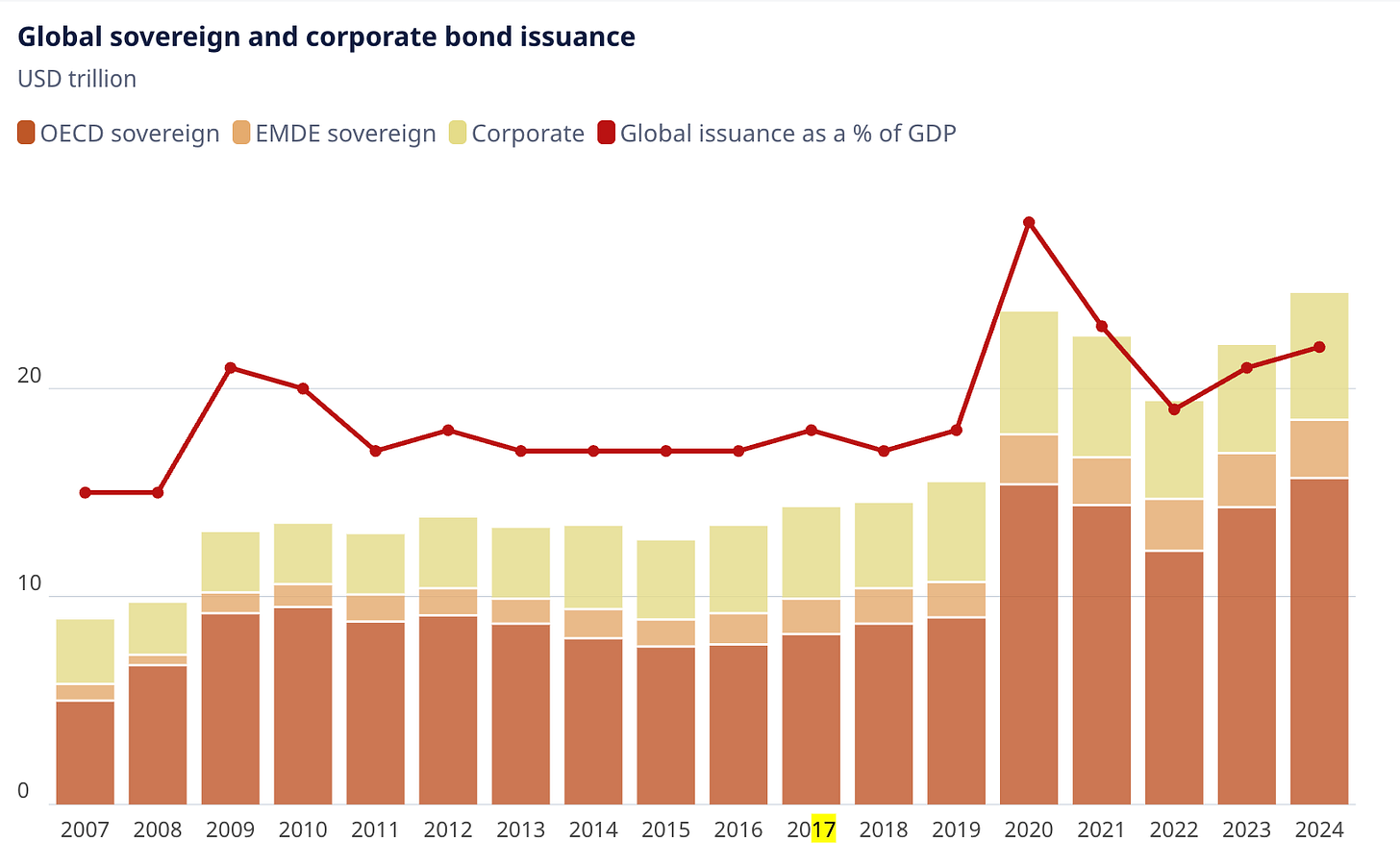

There is also an international component. The UK government is not the only one out there looking to borrow money. A recent OECD report on government debt estimates that sovereign bond issuances by member states will rise to $17 trillion this year, up from $14 trillion in 2023. Throw in Donald Trump’s threats to Federal Reserve independence, reduced demand from defined benefit pension funds and the Bank of England’s sale of gilts and it’s something of a perfect storm.

Today, the Financial Times reports that leading bond investors have urged the chancellor to cut spending, rather than rely solely on tax rises. Well, they would say that, wouldn’t they? Except, these are the people lending us the money and, in the words of Harold Wilson, we can’t kick our creditors in the balls1.

Reeves shows no danger of morphing into Liz Truss — she retains credibility with the markets (as well as a grip on reality). Nor does she have to listen to investors demanding large spending cuts. But relying on ever more niche bits of tax code is a hostage to fortune, and may have other harmful consequences (see bank shares falling following fears of a tax hike on the sector.)

Recall that were winners from Osborne-era austerity. Though taxes are at their highest level since the 1940s, income tax and NICs have fallen since 2010 for most people. As a result, at the point of the last election, the effective personal tax rate for the median earner with no children fell to the lowest point since 1975. Will the chancellor be tempted to claw some of that back?

Ultimately, Reeves doesn’t need to morph into Truss to lose market confidence — she just needs to run out of road or into unhelpful Office for Budget Responsibility projections2. And with hundreds of billions in taxes apparently off limits, welfare reform politically difficult and significant global headwinds, her room for manoeuvre is shrinking.

This was in response to a Labour colleague asking why he did not condemn the Vietnam War

Productivity growth is the one to look out for