Rachel Reeves can't just play the hits

Britain’s patchwork tax system won’t survive the demands of the next decade

“You can’t just point at things and tax them!”

Who said it? A) Milton Friedman, B) Kemi Badenoch, C) Mr. Burns or D) Liz Truss

Is that your final answer?

I did you dirty, I’m afraid. It was in fact former Hear’Say member and runner-up on the sixth series of I'm a Celebrity... Get Me Out of Here, Myleene Klass. The occasion was a 2014 edition of ITV’s late night political debate show, The Agenda. The subject was the Labour Party’s proposed mansion tax, and the object of Klass’s disdain was none other than Ed Miliband himself.

Klass’s comment was pure camp, but it captured something governments do all the time: they tax what is easy, visible and frankly attached to the ground rather than what is most economically efficient. And in doing so, they often store up bigger problems down the line.

Of course, governments have pointed at things and taxed them since pharaoh was in short trousers. From around 3000 to 2800 BCE, Ancient Egyptian authorities employed collectors and imposed levies on goods such as cooking oil and grain harvests.

Fast forward a few thousand years and in Britain, you can generally expect to pay tax when goods and services are exchanged. So, buy a Mars bar and you’ll pay VAT. Sell shares, and you’re liable for capital gains tax. Die (a form of exchange, I suppose) and your beneficiaries pay inheritance tax. None of these are especially popular, yet they often feel fairer than the alternative.

Safe as houses

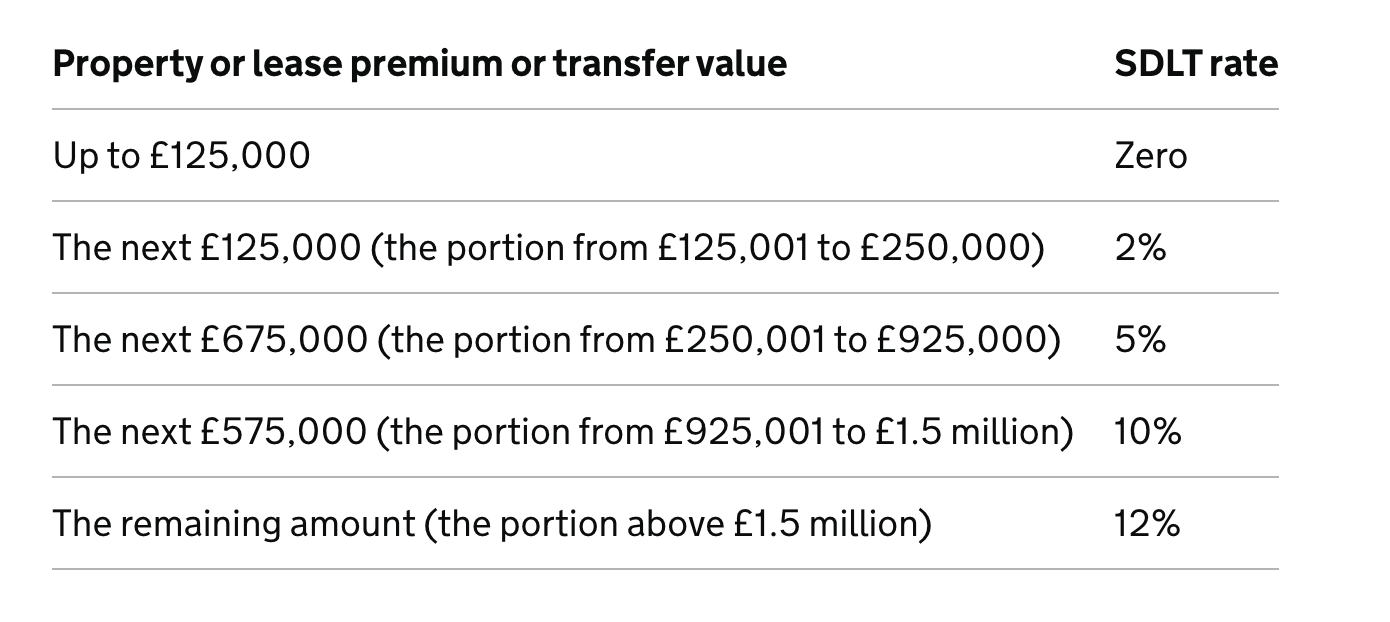

Take stamp duty land tax (SDLT), a tax paid on property over a certain price. It is moderately progressive, with rates increasing in line with the purchase price. It also raised a handy £15bn in 2023-24. But that haul comes at a steep price. SDLT distorts the housing market, penalises people who want to move and reduces labour mobility. It is not for nothing that the Institute for Fiscal Studies’ Paul Johnson calls it “the worst tax that we have”.

Yet from the Treasury’s perspective, stamp duty is a simply marvellous innovation. It is easy to collect1 and hard to avoid, being a levy on the transfer of a large, fixed object. That it is a tax on mutually beneficial transactions is not at the top of the Exchequer’s concerns. Britons seem to prefer it too, given that the alternative would be a more traditional property tax that would probably not be predicated on house prices in April 1991.

The problem

So what, I hear you ask? (You’re still bitter about the Myleene Klass bait-and-switch, aren’t you?) Well, come the autumn, Rachel Reeves is likely to be in a position of needing to raise quite a bit of revenue. The problem is that she is hamstrung by her party’s manifesto, which ruled out raising the three largest taxes: income tax, national insurance and VAT. As a result, the chancellor is left scrambling to squeeze ever more money out of seemingly random bits of the economy.

Instead of reversing Jeremy Hunt’s fiscally irresponsible cuts to national insurance (cuts which no voter appeared to notice) the government instead chose to tax inherited agricultural assets, increase stamp duty on second homes and buy-to-let properties, rolled pensions into inheritance tax and raised the lower and higher rates of capital gains tax, amongst other things. That is, it made the tax system even more complicated and inefficient.

This piecemeal approach is also politically damaging. Those on the receiving end — like farmers — feel attacked, get angry, organise, and make life difficult for the government. Broad-based taxes, though politically difficult, spread the burden more widely and create fewer identifiable losers.

No government can dodge this forever. An ageing population, a more dangerous world and a warming planet all mean one thing: we’re going to need more revenue. Sure, the rich can be milked a little more, but eventually, someone is going to have to tell the truth: all of us — including those fabled working people — will need to pay more tax.

Similar to the much-maligned fuel duty, which is paid on leaving the refinery, and technically not by drivers

Lower SDLT / increased volume turnover / increased related expenditure / more tax revenue.

“Simple” or “shoud’ave gone to specasavers”