Britain and Germany go their separate fiscal ways

'Whatever it takes' vs 'Crisis? What crisis?'

At first glance, it makes little sense. How is it that the UK and Germany – both locked in a prolonged period of economic stagnation, both facing the twin challenges of decarbonisation and an ageing society, both confronting a hostile Russia, a revisionist China and a newly unreliable United States – can take such divergent courses of action?

On Wednesday, Rachel Reeves is expected to deliver a Spring Statement in which she will announce cuts to spending, in particular welfare1, in an attempt to meet her fiscal rules. This is in addition to spending plans that already imply real-terms cuts this parliament to unprotected departments, including justice and local government.

At the same time, incoming German chancellor Friedrich Merz is ripping up his country’s infamous ‘debt brake’, the constitutionally enshrined mechanism that strictly limits government borrowing.2 Consequently, spending on defence, cybersecurity and intelligence exceeding 1% of GDP can now be funded by new debt. This alongside a €500bn infrastructure investment plan.

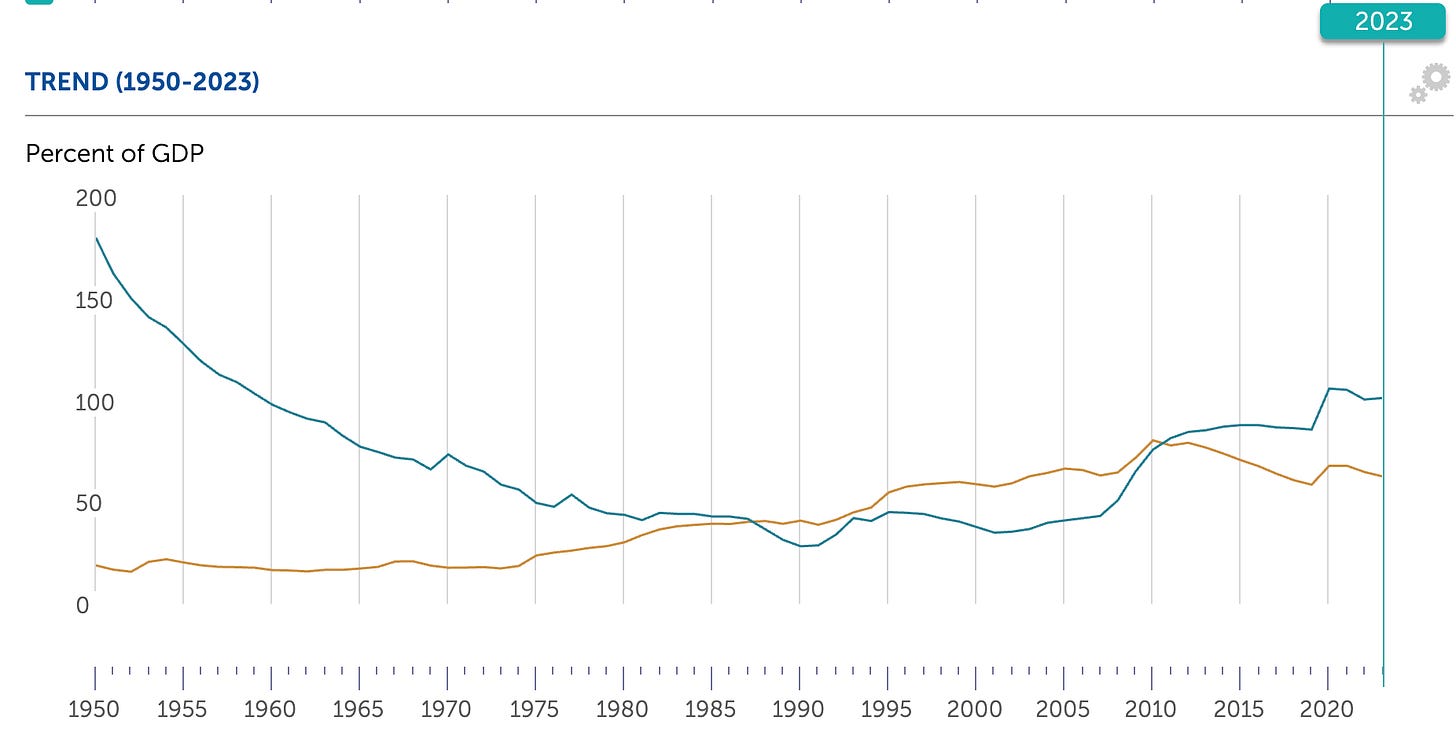

A quick Google search (as long as you ignore the AI garbage at the top) seems to explain the discrepancy. Germany has a debt-to-GDP ratio of around 63%, compared with Britain’s 95.5%. Yet, this is where a little knowledge is a dangerous thing.

It is absolutely the case that Berlin has greater flexibility than London because it is starting from a far stronger fiscal position. All else being equal, I would rather the UK enjoyed German levels of public debt (and while we’re at it, French levels of productivity3.) But this is far too simplistic a reading.

Even the fact that German borrowing costs jumped following Merz’s announcement is not quite as it seems. As the economist Duncan Weldon – author of the brilliant Two Hundred Years of Muddling Through and the upcoming Blood and Treasure – points out, the rise in German bond yields reflected financial markets pricing in higher growth.

Indeed, borrowing costs rise and fall for all sorts of reasons. The difference in this case, unlike in the aftermath of the 2022 ‘mini-Budget’, when gilts rose, sterling fell and equities took a beating, is that the euro rose alongside German equities. In other words, the markets were not taking fright at perceived fiscal risks.

Clearly, something has changed in Germany. A realisation that there will be no return to the status quo ante, and the deal every chancellor has made for decades. Niall Ferguson, the renowned historian and senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, sums it up with typical elan: “The Americans provide our security, the Russians provide our energy, and the Chinese provide our export market. Guess what? It's all gone.”

And so while Keir Starmer is happy to be interviewed in the New York Times, calling the idea of choosing between the US and Europe “a big mistake”, Merz has few such misgivings. During a post-election debate last month, the leader of the CDU and an Atlanticist to his fingertips, remarked:

"I would never have thought that I would have to say something like this in a TV show but, after Donald Trump's remarks last week... it is clear that this government does not care much about the fate of Europe… My absolute priority will be to strengthen Europe as quickly as possible so that, step by step, we can really achieve independence from the USA.”

Of course, the fiscal position is vital for any government. Britain’s high levels of public debt represent a genuine constraint on government action. But that is not to say Reeves is entirely hamstrung. She could meet her fiscal rules without deep cuts to welfare either by raising taxes or pursuing pro-growth strategies, such as EU single market and customs union membership. Both would break manifesto commitments and therefore appear improbable. But unlike borrowing more, it is at least a choice freely made.

In reforming his country’s debt brake, the German chancellor has had his ‘Whatever it takes’ moment. The UK chancellor appears to be stuck in ‘Crisis? What crisis?’ mode.

The Financial Times estimates that stricter eligibility criteria could see tens of thousands of Britons lose 64% of their income, or almost £10,000

The German constitution had stipulated that the federal government can borrow only up to 0.35% of GDP

Workers in France are around 17% more productive than their British counterparts