Rachel Reeves is still unsackable

Even Starmer’s ruthlessness has limits

Keir Starmer’s path to power is littered with bodies. There are the internal political opponents, such as party general secretary Jennie Fornby and shadow cabinet colleague Rebecca Long-Bailey. But being a political ally confers little protection either — just ask Anneliese Dodds or Nick Thomas-Symonds. And that is before we arrive at the biggest sacrificial lamb of all.

The prime minister spent months courting and then waiting for Sue Gray to join as Downing Street chief of staff. She lasted three months in the job. Starmer seems to view this as a virtue. In an interview with The Telegraph last year, he said: “If I’ve got to take a ruthless decision in order to get to where I need to be to give them [voters] the country that they deserve, then that’s an easy decision.”

This ruthlessness is not always accompanied by equal servings of competence. Indeed, the attempted defenestration of Angela Rayner following the 2021 Hartlepool by-election defeat not only saw Labour’s deputy leader keep her job1, but also secure some new responsibilities as well. Still, it is a reputation the prime minister has deservedly acquired. But in the face of this irresistible force is an immovable object: Rachel Reeves.

Everybody hates Rachel

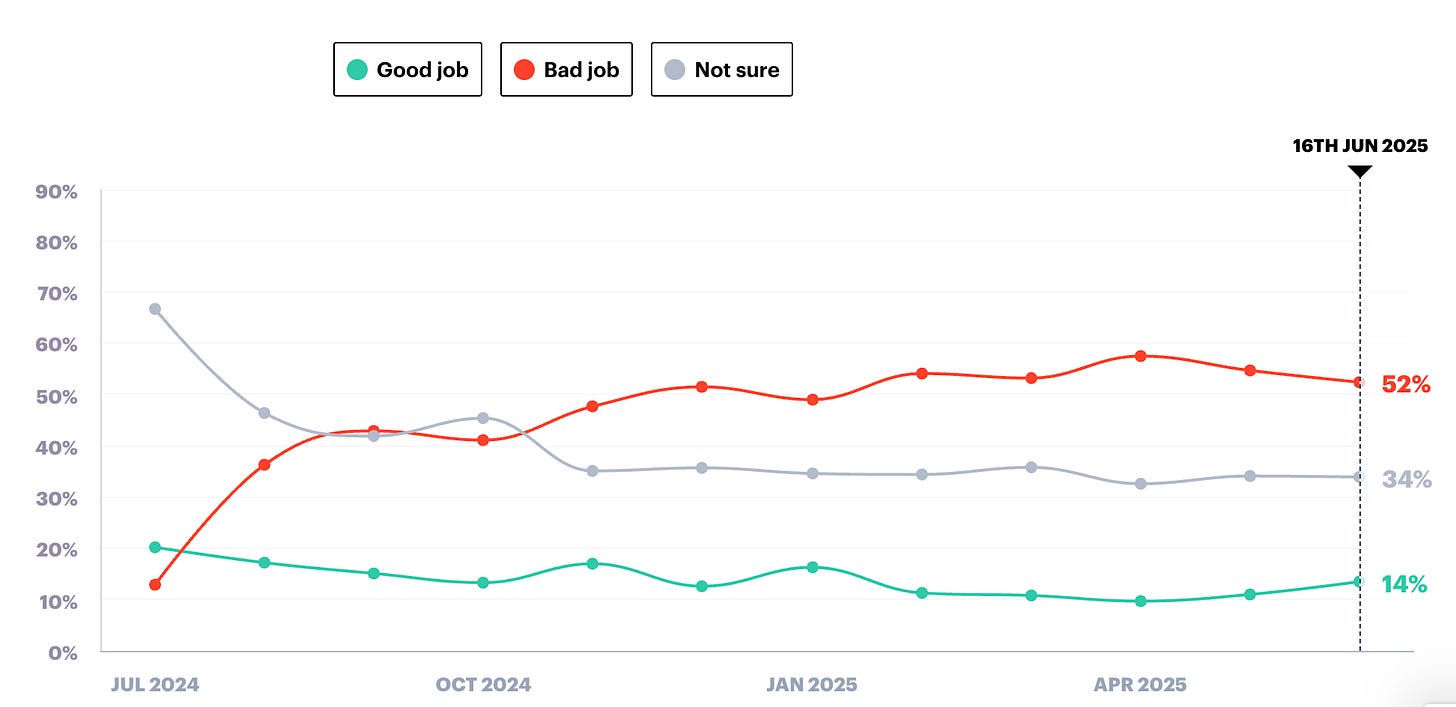

The chancellor is having a tough time of things. Just 14% of voters think she is doing a good job, compared with 58% who think she is doing a bad job, according to YouGov’s tracker.

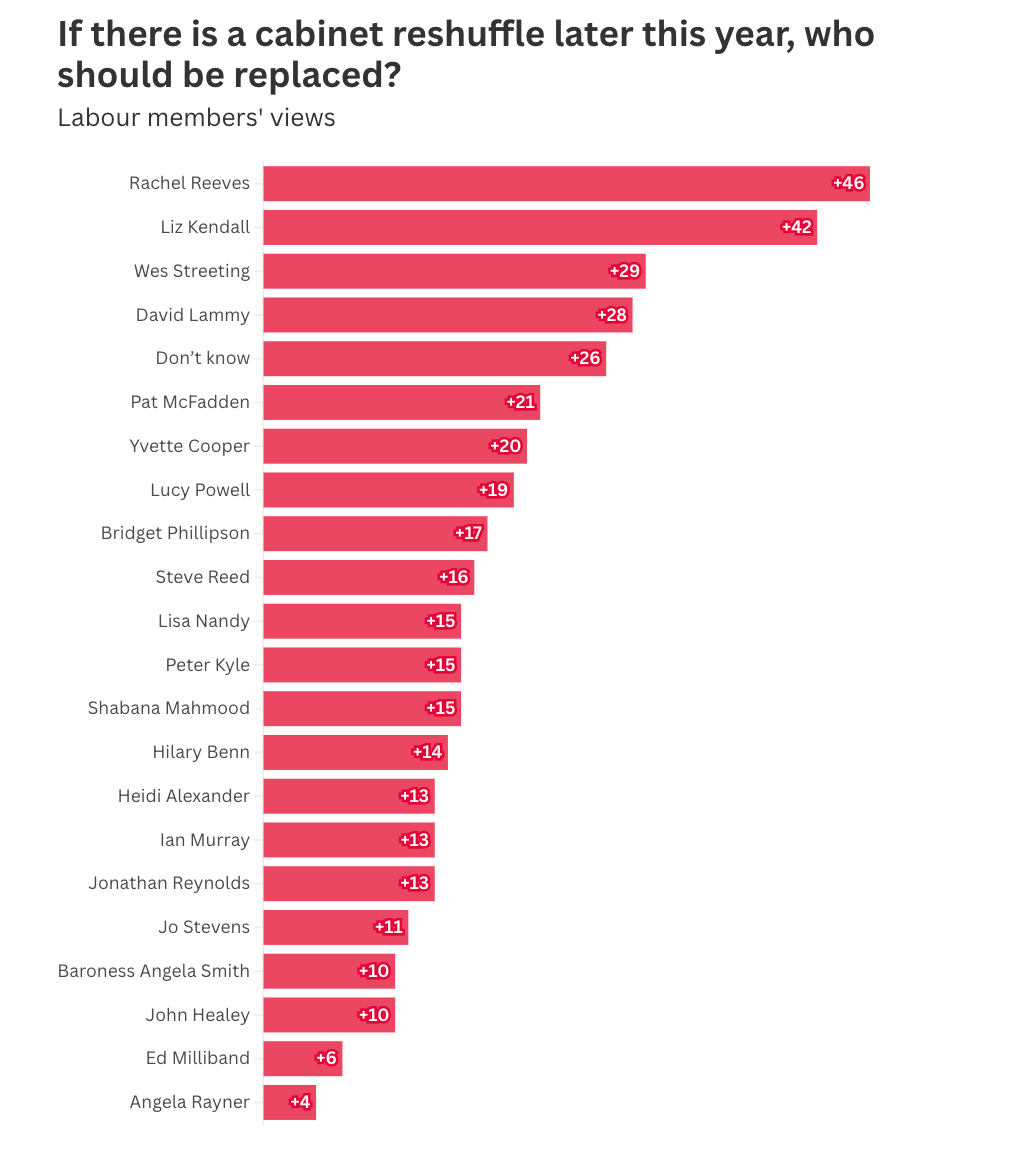

Party members scarcely hold her in higher regard. Reeves topped a recent LabourList/Survation poll asking which member of the cabinet should be replaced in a reshuffle.

There is little mystery to this. Labour members are — shock, horror — fairly left-wing and like left-wing things such as climate action (Ed Miliband) and housebuilding (Rayner) but don’t like right-wing things like benefits cuts (Liz Kendall). Meanwhile, Reeves is the public face of most unpopular spending decisions.

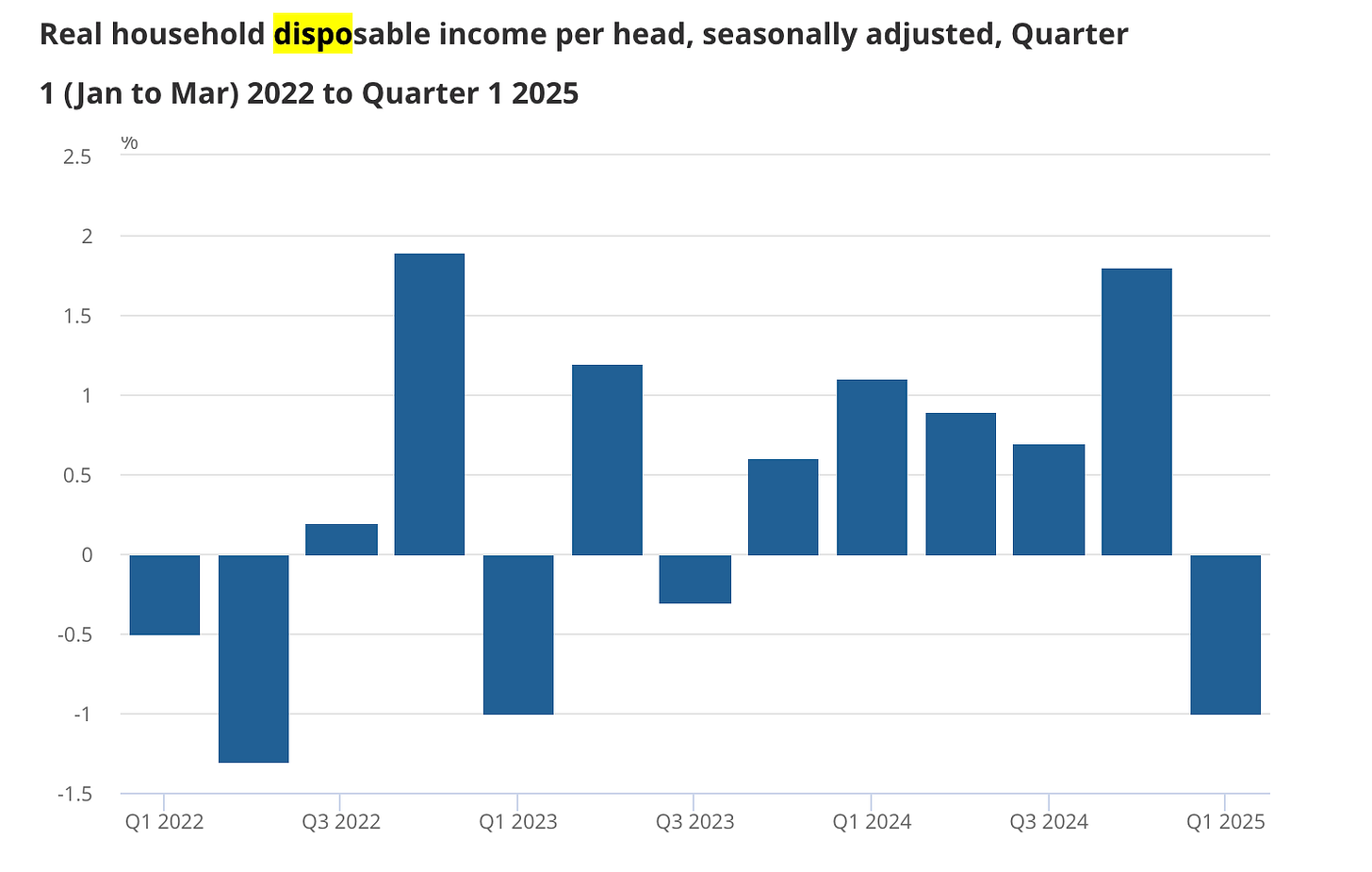

Then there is the chancellor’s actual performance. To the extent she has any real control over economic growth, things are not going well. GDP forecasts have been slashed, inflation is frustratingly sticky and there are some truly terrifying borrowing figures about. Meanwhile, real household disposable income per head fell by 1% in the first quarter of 2025, the sharpest decline for two years. And yet, and yet, Starmer will not remove Reeves — even if he wanted to2 — for one very basic reason: it would not solve his problems.

A brief history of the British government

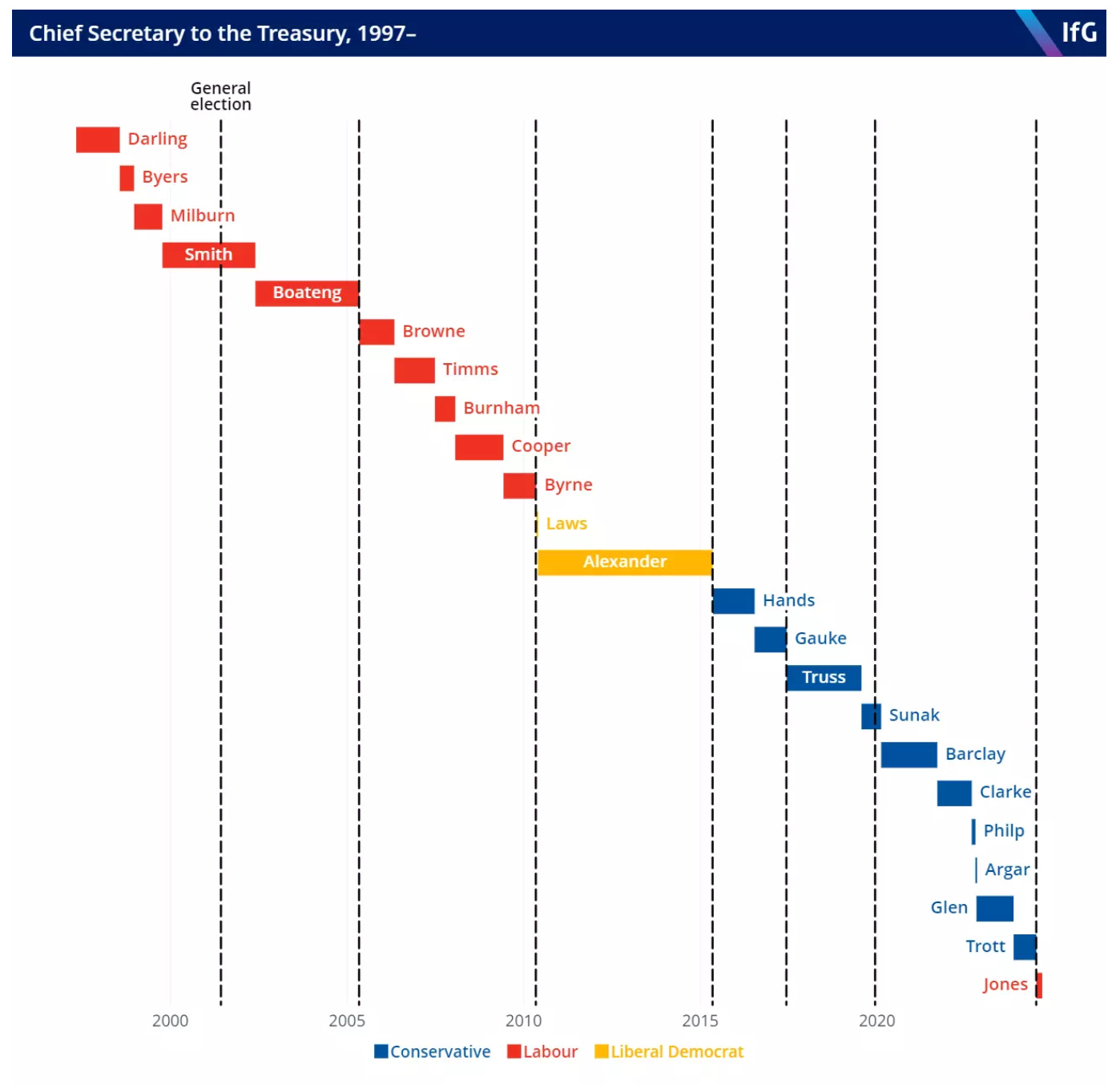

The British cabinet is hardly the platonic ideal of stability. Since 1997, there have been 23 chief secretaries and 26 housing ministers. On the basis that no one knows what they are doing in a job for the first six or so months, it is perhaps unsurprising that Britain faces fiscal problems and a housing crisis.

However, the fag end of the last Conservative government aside, there has been some stability in the occupant of Number 11. For roughly five decades after the 1970s, chancellors lasted an average of four years, a figure brought down by Iain Macleod dying four weeks into the job, and John Major lasting little more than a year before taking the top job. Strip those two out, and the average tenure jumps to five years.

This is not always a result of benign neglect on the part of the prime minister. On the extreme end of things, David Cameron and George Osborne got on famously well while Tony Blair and Gordon Brown were scarcely on speaking terms by the end. Yet even the relationships in the middle are characterised by built-in tension and mistrust.

But the principal reason is self-preservation. We know that Blair considered sacking Brown, who in turn contemplated removing Alistair Darling in favour of Ed Balls, while Theresa May was poised to sack Philip Hammond but for her misplacing a parliamentary majority. Ultimately, none of them acted, and that is because losing a chancellor — for whatever reason — is usually a pretty good indication that things are nearer to the end than the beginning.

Suppose Starmer did demote Reeves. What would that say about him? How could he plausibly lay the blame for the government’s fiscal and economic woes on the person he handpicked, defended and whose policies he repeatedly endorsed? Liz Truss tried it with Kwasi Kwarteng, of course, and look how that worked out.

There is a reason we refer to it as the ‘Truss mini-Budget’ rather than the ‘Kwarteng mini-Budget’. The prime minister helped to write it, to egg on her chancellor and clearly believed in it. Consequently, it was simply not credible that she could sack the bloke who delivered the speech, reverse her entire governing philosophy and just stagger on.

Even Margaret Thatcher recognised the problem. Having lost her “brilliant” chancellor, Nigel Lawson, to resignation in October 1989, the prime minister was forced to compromise. Hence, where Lawson had failed to convince her to agree to Britain’s entry into the Exchange Rate Mechanism, Major succeeded. Thatcher was simply no longer in a position to refuse, lest she lose a second chancellor in as many years. In this way, the new recruit is often more powerful than the stubborn incumbent.

Starmer has cultivated a reputation for doing whatever it takes to win. Staying in the shadow cabinet when others quit. Calling Jeremy Corbyn a friend before kicking him out of the party. Hiring and firing aides at will. But Reeves is the one figure he cannot simply leave to the wolves. Not least with his popular and ambitious deputy poised to feast on the remains.

As the elected deputy leader, Starmer could not remove Rayner from that position

After a little obliqueness, Downing Street confirmed earlier this year that Reeves will remain in her role "for the whole of this Parliament"