The attention deficit

Britain’s chronic economic stagnation — not a single bad month — is the real crisis

Do you remember the double-dip recession of 2011-12? As the nation was gearing up for the Olympic Games, the economy shrank by 0.2% in the first quarter of the year, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS). Coming fresh off a contraction of 0.3% in the final three months of 2011, that added up to a recession. Cue calamitous headlines and shadow chancellor Ed Balls1 doing the flatlining gesture that so riled David Cameron at PMQs.

The only problem with your memory is that it did not actually happen. The ONS did its calculations and the media its reporting, but the recession, it turned out, was a fiction. In June 2013, it was simply revised away. Instead of shrinking by 0.2% in the first quarter of 2012, the economy merely flatlined. Cue celebrations in Downing Street.

But there is another problem. While no recession is certainly preferable to the alternative, a flatlining economy is still… really very bad. In fact, the revisions to GDP which wiped out that contraction probably contained more bad news than good. As Sky News’s Ed Conway pointed out at the time, the ONS simultaneously revealed that the 2008-09 recession was, in fact, deeper than previously thought, and that the UK economy was 4% below its pre-crisis peak, instead of the 2.5% originally reported.

The narcissism of small differences

Of course, there are times when small differences matter a great deal. For example, the difference between winning an election by one vote and losing by one is substantial. Meanwhile, keeping as opposed to losing your job in a recession will be of high importance to you and your family. But from a macroeconomic perspective, the difference between 0%, 0.1% and -0.1% is minimal. Fancy people call it the difference between the signal and the noise.

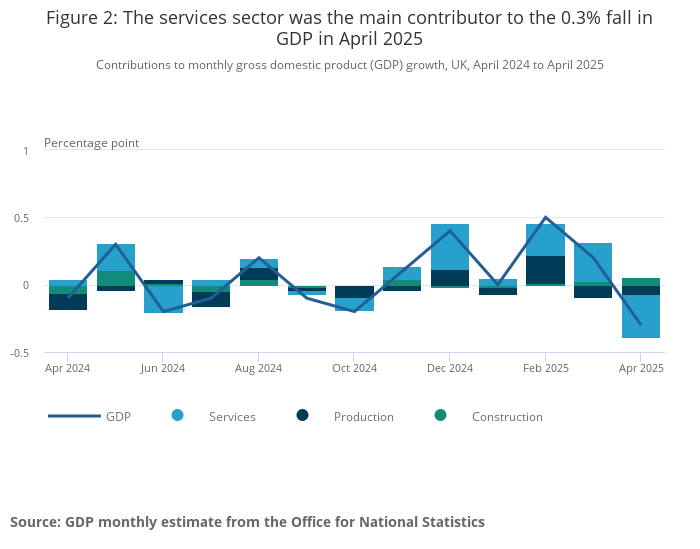

I was reminded of this when various media outlets breathlessly reported that the UK economy had shrunk by 0.3% in April. Clearly, this represented both bad news and even worse timing for Rachel Reeves, coming straight after the Spending Review. But it is also deeply unhelpful to suggest this portends something of a crisis. Consider the following:

Economists had expected a contraction of 0.1%, so this was worse

But growth in March was an almost frothy +0.2%

But it is still embarrassing for a chancellor who has made growth her top priority

But some of the fall can be attributed to Trump’s tariffs, which led to the largest ever monthly drop in goods exported to the US

But the expiration of the stamp duty holiday had a negative impact on legal and real estate companies

And so on.

I mean, just look how much monthly GDP figures tend to jump around. Obsessing over them is a bit like someone on a diet who weighs themselves every day, ignoring the fact that the body fluctuates all the time depending on water retention, food intake, physical activity and hormonal changes.

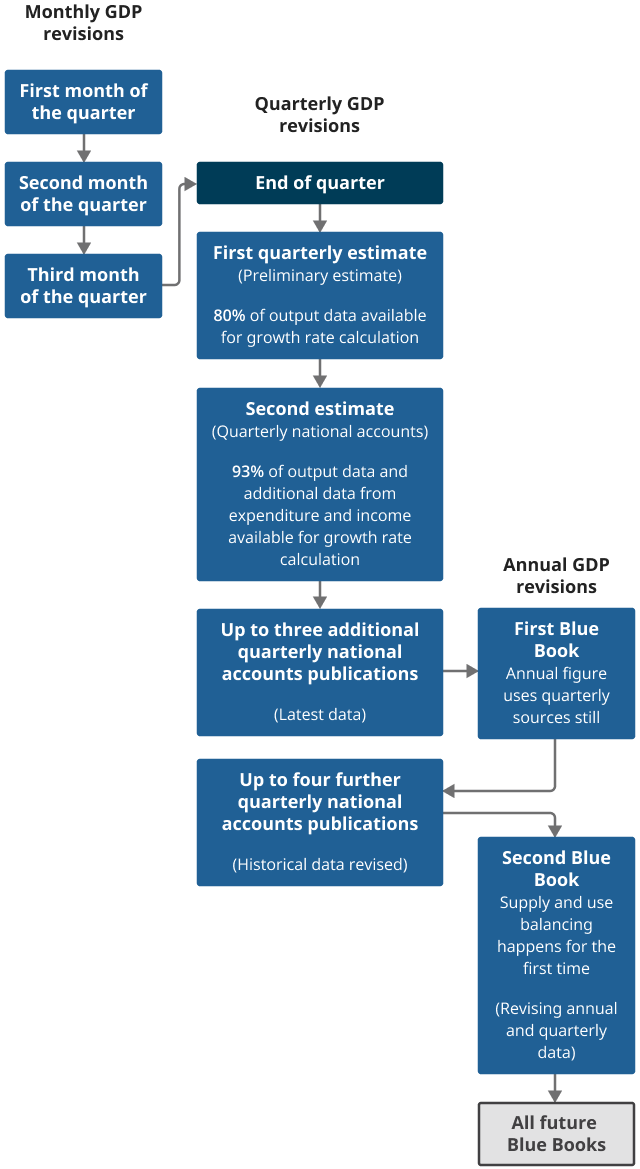

Furthermore, there is a reason why the ONS calls its GDP monthly figures an ‘estimate’ — they are subject to revision. The UK economy is large and contains multitudes! See below for the ONS’s process.

What matters is not one month’s figures, but rather the general trend. And here, one can be as despairing as one likes. Growth forecasts are being cut left, right and centre. While on a longer timescale, the UK economy has not enjoyed sustained growth of the sort to write home about since, well, the mid-2000s.

That is old news, certainly compared with an ONS data dump hot off the presses. But an economy that is about to enter its third decade of flatlining growth and living standards really ought to be a front page story every day. That it is not, is evidence that we have simply grown numb to decline.

Reminds me of stock market reporting by the media. The market has shed over $50bn today, the biggest loss for 3 days.