The Great Compression

A rising minimum wage has helped the worse off — but is now edging uncomfortably close to the middle class

For most people, their ‘Portillo moment’ arrived in the early hours of 2 May 1997, when the then Secretary of State for Defence and frontrunner for the Tory leadership lost his hitherto safe seat of Enfield Southgate to a fresh-faced Stephen Twigg. Not for me, Clive.

That was on the morning of 3 February 2000 when, just two days into his new job as Shadow Chancellor and scarcely two months since his return to the Commons, Michael Portillo stood up at the despatch box and announced with practised insouciance that “the next Conservative government will not repeal the national minimum wage.”

It was certainly a surprise. The Tories’ 1997 manifesto described a minimum wage as “a cruel trick on working people” and promised that no Conservative government would introduce one. Portillo himself had called a minimum wage “a truly immoral policy” during the campaign, warning that the worse off would lose their jobs.

A dash of history

The UK had some form of statutory regulation of minimum pay for large parts of the 20th century, albeit without a national minimum wage. Fair Wage Resolutions were established as far back as 1891, as part of an effort to eradicate unfair competition for public sector contracts by those seeking to undercut recognised pay rates.1

Wage Councils were introduced several years later, and by 1953 peaked with a coverage of some 3.5 million workers, allowing for a form of collective bargaining for the low paid. But as unionisation fell from its 1980 peak2, the number of people living in households with an income below 40% of the median doubled between 1985 and 1993.

The 1985 Labour conference (better remembered for that Neil Kinnock speech) voted in favour of a motion supporting a national minimum wage of two-thirds of male median earnings. However it took until 1992 for such a commitment to appear in the party’s election manifesto. At the time, it was something of an electoral millstone, with the Tories painting it as dangerously high.

The difference in 1997 was that Labour’s promise was only to the principle of a minimum wage, rather than a definitive level, with a further commitment to establish the Low Pay Commission — later placed on a statutory footing — to make recommendations.

The Commission’s first report highlighted a number of abuses, including a job advert for a nightwatchman for £1 an hour for a 100-hour week — in which the employee had to provide their own dog.

How much?

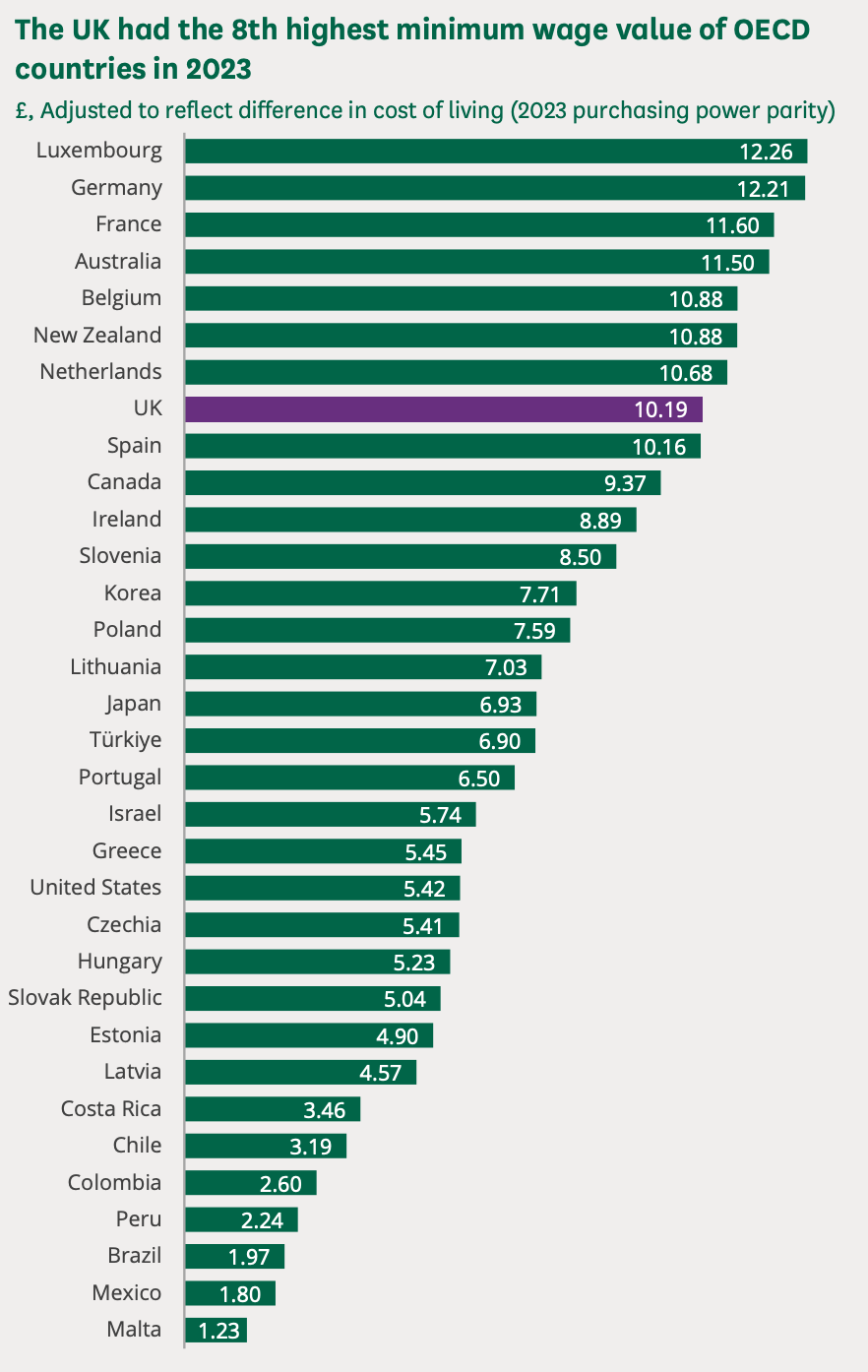

In 1999, the minimum wage for those aged 22 and above was set at £3.60 an hour. By 2025, it hit (for those 21 and older) £12.21, an increase of 6.7% on the year before. The UK’s minimum wage was already relatively high compared with other OECD countries. In fact, the UK had the eighth highest minimum wage out of 24 OECD members in 2023 — after adjusting for the cost of living.

One notable change has been the rise of the minimum wage compared with median earnings. In 2023, it accounted for 60% of median earnings. Another has been the rising number of people benefiting from it. In 1999, it was around 3.4% of all jobs, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies. Just before the Covid-19 pandemic, this had doubled to 7% of employees.

As unemployment has remained low, successive governments have been only too keen to boost the minimum wage. Consequently, as of last year, the lowest paid workers in Britain enjoyed a roughly 70% rise in the minimum wage over the previous quarter of a century — even accounting for inflation.

The benefits of this are obvious — the lowest paid are earning more money, all funded by businesses rather than by government.3 As noted above, this is a direct result of government policy. Even the previous Conservative government established a new target for the minimum wage to hit two-thirds of median earnings by 2024. But not everyone is happy.

First, there are the employers who have to pay it. I’m not expecting much sympathy here, though many economists do say that rising food bills (food inflation is currently running at an uncomfortable 3.8%) is driven in part by increases to the minimum wage, as well as the hike in employers’ National Insurance Contributions.

The Great Compression

Even putting to one side the cost to employers, there is the growing issue of convergence or wage compression.4 That is, the increasingly narrow gaps between employees on different rungs of the corporate ladder.

Someone on the minimum wage working 40 hours a week full-time can earn roughly £25,000 a year. At the same time, the average salary for those on a graduate scheme is £29,500 per year according to Indeed, an employment website. This figure includes both new graduates and those with experience.

Workers would always rather be paid more than the minimum wage, but plenty of managers are feeling pretty aggrieved at the prospect of earning only a little more than their subordinates. This is not for reasons of mere income, but also status. Why bother climbing the greasy pole, taking on more grief, responsibilities and responding to those late night emails, if you’re barely earning more than the people who get to switch off when they leave the office or who lack similar qualifications.

Clearly, this is not solely the ‘fault’ of the minimum wage, let alone the people on it. Indeed, we still face challenges from the rise of the gig economy which has seen many plunged back into insecure and sometimes dangerous work. But at the same time as governments have returned to the minimum wage well, middle-class wages have endured regular bouts of stagnation.

Recently, the journalist Harry Wallop reported on the ‘middle-class’ shock of spending north of £100 for a family of four at casual restaurants such as Pizza Express and Wagamama. More, he notes, than the cost of a 32-inch television. This newsletter is already running long and I’m not about to start blathering on about Baumol’s cost disease.

But the middle are undoubtedly being squeezed. They can’t get close to affording the lifestyle of the rich, with their nannies and lie-flat business class seats. On the other hand, they can’t even feel as if they’re at least doing much better than those they consider below them, both in educational and social terms.

People care not just about how much they earn, but where they sit in the pecking order. That doesn’t mean governments should stop helping those at the bottom. But they shouldn’t pretend that status anxiety is mere vanity. Middle-class resentment has a tendency to become pre-revolutionary.

I mean, have you been in a Côte fifteen minutes before curtain up?

Clearly, government must fund NMW rises for those employed in the public sector, at some cost of departments

Halfway through writing this, I remembered there was an excellent Bagehot column on this subject a year ago. There’s always a Bagehot column anytime I think I’ve come up with an idea…