Whatever happened to the balance of payments?

It once brought governments to their knees. Today, it barely registers

Uncollected rubbish piling up in the streets, NHS workers blockading hospital entrances and, most famously of all, the bereaved being forced to grab their own shovels as the gravediggers walked out. The Winter of Discontent of late 1978 to early 1979 shone a blinding light on excessive trade union power in Britain and opened the door to what would eventually be called Thatcherism.

Yet it was the crisis of 1976 that really signalled the death knell of a certain brand of economic management. It was not all James Callaghan’s fault, of course. But on his first day in Number 10, the prime minister was informed that the pound was sinking rapidly and, given the billions spent by the Bank of England to prop up sterling earlier in the year, a loan from the International Monetary Fund was unavoidable.

En route to Heathrow for a Commonwealth finance ministers’ meeting in Hong Kong, chancellor Denis Healey famously turned his car around and raced to the Labour Party conference in Blackpool. Given how tightly controlled these events are today, the theatrics are really quite remarkable. Healey took to the stage (for just five minutes, as dictated by absurdist party rules) and announced he would negotiate with the IMF. This, he told the baying delegates, would mean “things we do not like as well as things we do like”. Watch along just for the magnificent eyebrows.

And so, a mere three decades after winning a total war and running a global empire, the British government went, as the nomenclature demands, ‘cap in hand’ to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Of course, as is so often the way with these things, it was all entirely unnecessary.

The balance of payments1 deficit had been rectified well before the IMF demands were enacted, with Healey later bitterly noting: “If I had been given accurate forecasts in 1976, I would never have needed to go to the IMF at all.” Even worse for Healey is that today, the balance of payments is considered something of an irrelevance2.

But first, some graphs

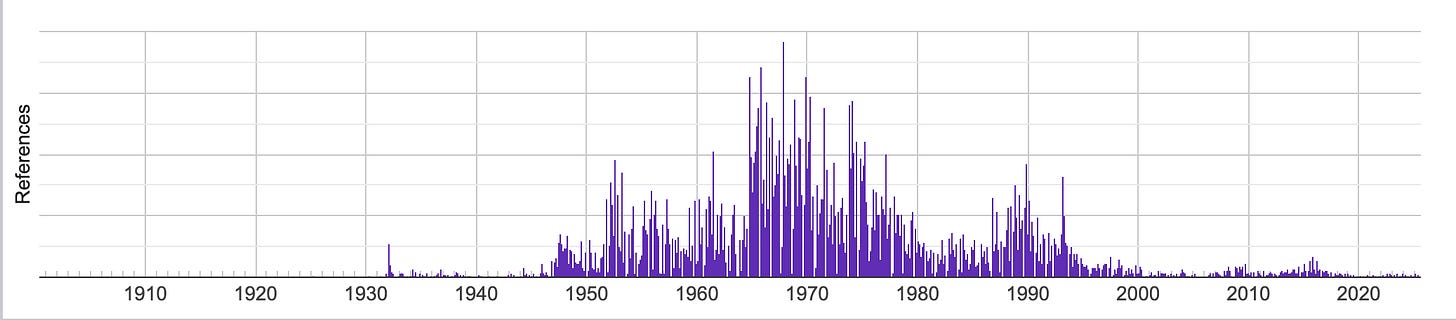

Look below at the number of times the phrase ‘balance of payments’ was uttered in parliament over the last 100 or so years. It appears to be some sort of post-war invention, which peaked in the 1960s and 1970s, before declining and then virtually disappearing by the early 2000s.

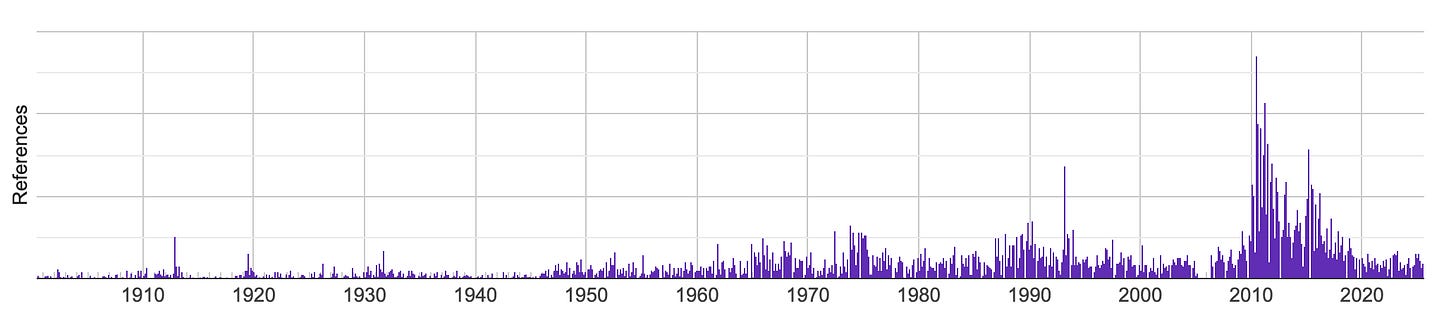

Compare that to mentions of the ‘deficit’, which enjoyed its heyday in the Cameron-Osborne years. This is, of course, hardly a scientific approach, but useful nonetheless in illustrating elite political preoccupations.

So, here’s my question. My lifelong obsession, in fact. Given all of the above, why is it that no one talks about the balance of payments anymore? It is not as if economic metrics have ceased to dominate public life. Indeed, politicians and commentators get terribly excited by even largely meaningless data releases, such as monthly GDP figures. Meanwhile, growth and debt forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility appear to determine practically every move Rachel Reeves makes.

Sinking, then floating

The story can be traced back to friend of the newsletter, the Bretton Woods system, in which the value of sterling was fixed relative to the US dollar. Under Bretton Woods, financial policy was inherently limited by the fixed exchange rate and the balance of payments. This was meant to be self-stabilising, which may come as a surprise to anyone alive at the time. The UK economy endured a succession of balance of payments problems in the three decades following 1950, and experienced devaluations in 1949 and 1967.

Then, the Bretton Woods system effectively collapsed in 1971 and sterling floated. Under fixed exchange rates, the UK either had to generate currency or spend precious reserves. But a floating currency meant that, as long as foreigners were prepared to be paid in sterling, and were content with not knowing exactly how much it was worth on a given day, everything was kind of OK.

A few other things happened. North Sea oil came online which, in the words of a recent Bank of England working paper, transformed sterling from “an ailing reserve currency to an emerging petrocurrency.” There was also the disintegration of the sterling area, the lifting of capital controls in 1979 and more devaluations. This made inflation targeting a serious challenge, but the balance of payments drifted into the background.

That’s not change, that’s more of the same

Still, is it just me or does it all feel a little… flimsy? On my first day at the Treasury, I asked a senior (and now even more senior) civil servant what had happened to the balance of payments as a serious economic concern. His answer was simple: Britain kept running big deficits and bad things did not happen. I appreciated his candour — but it was not wholly reassuring.

A country that persistently borrows from abroad to fund consumption — rather than investment or production — is still taking a gamble on the goodwill of strangers. For now, the world is content to hold sterling and buy up UK assets, thanks in part to our deep capital markets, rule of law and trusted institutions. But confidence is not a permanent feature of the financial system — it is a mood. And moods have an annoying tendency to shift.

Clearly, it would be better if the UK produced more things, whether goods or services, that people in other countries wanted to buy. But as long as foreigners are willing to be paid and save in sterling, everything is fine. Or, at least, bad but for different reasons.

TL;DR how much we owe other nations for the goods and services we buy from them compared with how much they owe us for what we sell to them

An unexpectedly poor set of balance of payment figures was even blamed for Harold Wilson losing the 1970 election, after an order of two Boeing 747s by BOAC, forerunner to British Airways, sent the numbers into the red (there is always an aviation angle). Today, they are not even greeted by a shrug