Why we're focused on the wrong sort of crime

As violent crime falls, digital scams are quietly costing victims millions

My mother provides an invaluable service. Throughout the year, she texts her children (ages 36, 38 and 40) to inform them of upcoming family birthdays and anniversaries. I really ought to write these down. Until then, I shall continue to appreciate her taking on the administrative burden.

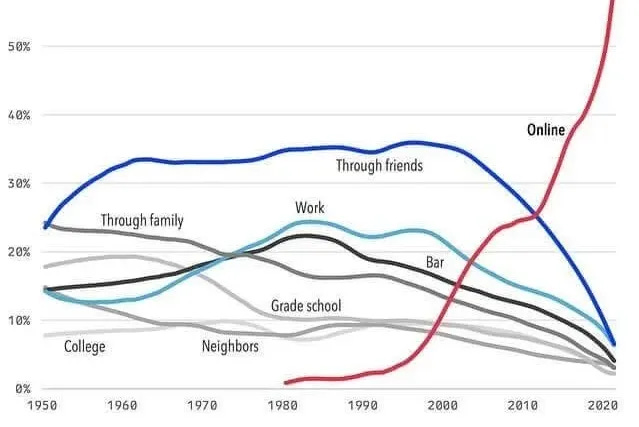

But there’s one anniversary she forgot to mention, largely because it would have been extremely weird. That was 21 April 2025, which marked 30 years since the launch of Match.com, the world’s first major online dating website. Since then, ever more couples have met online, bringing joy, love, and endless “Hey”, “Hi”, “How’s your day going so far?” messages that never actually lead to a medium-bodied chardonnay at All Bar One.

But online dating has also spawned the rise of so-called romance scams. A recent report by Barclays found that these have risen 20% year-on-year, with one in 10 British adults either being targeted, or knowing someone who has. Victims lost on average £8,000 in 2024, a figure that rises to £19,000 for those aged 61 and over.

It is a particularly cruel form of theft. Romance scammers exploit people’s trust and desire for human connection. More than a quarter of victims said they were feeling lonely when the scammer contacted them, while a fifth said they ignored red flags because they were excited by the chance of finding love.

Of course, scammers are everywhere — preying on people expecting a DPD delivery, waiting on a job offer or corresponding with HMRC. Yet despite how pervasive and costly this kind of crime has become, public discourse remains fixated on a very different threat: street crime.

Listen to Nigel Farage, leader of Reform UK, and you might be forgiven for thinking that crime, particularly the violent kind, is surging in Britain. Polling suggests a receptive audience for this sort of talk. YouGov’s tracker finds that 24% of respondents now list crime as the most important issue facing the country, up from a low of 11% in January 2021, when Brits were mostly thinking about Covid-19.

Yet this is at odds with much of the data. The Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) is an interviewer-administered face-to-face survey which asks people about their experiences of crime in the past year. It shows that crime, including violence, theft and criminal damage, has largely fallen over the last 10 years1. This matches police recorded crime.

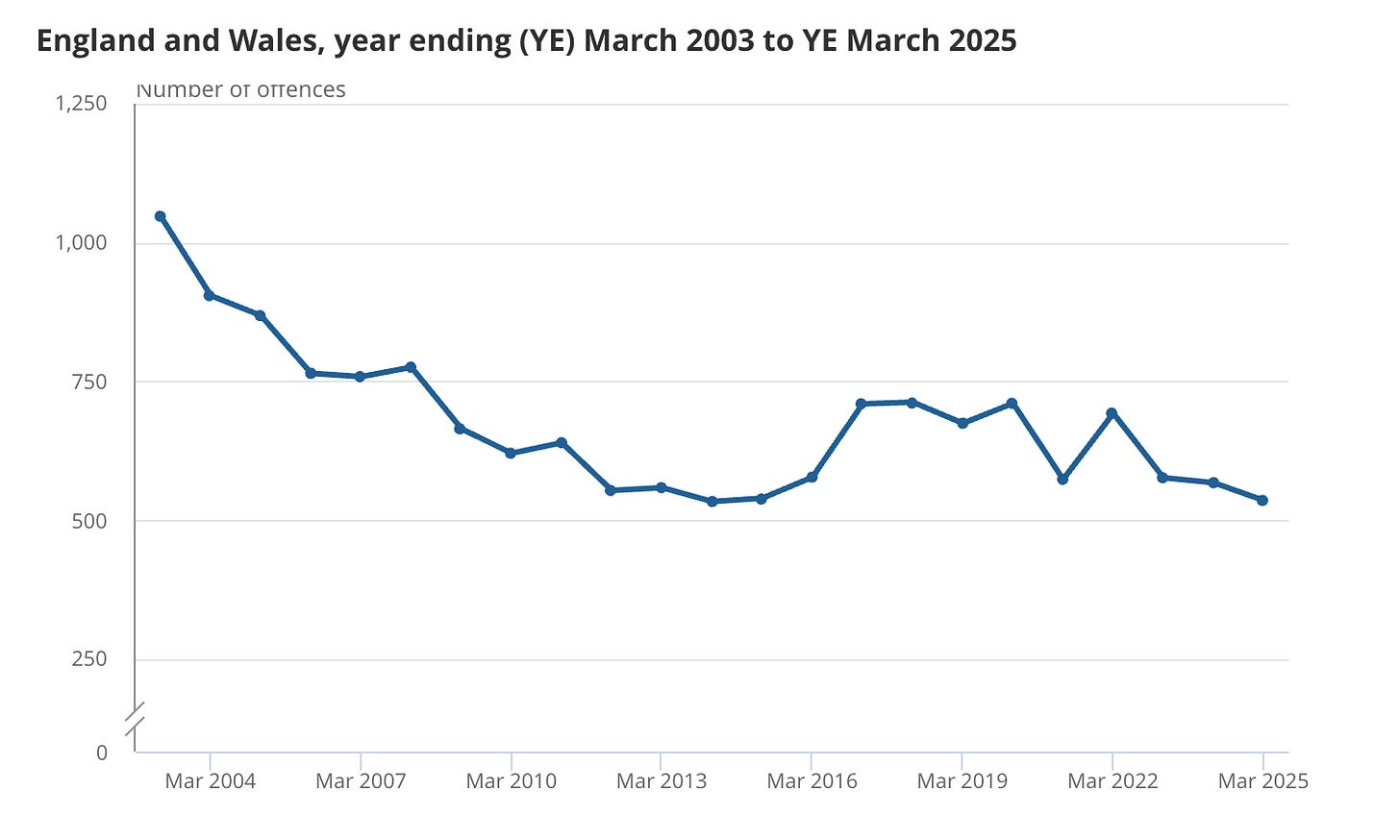

Take homicides, which are down 6% in the last year and are half the figure from 2003.

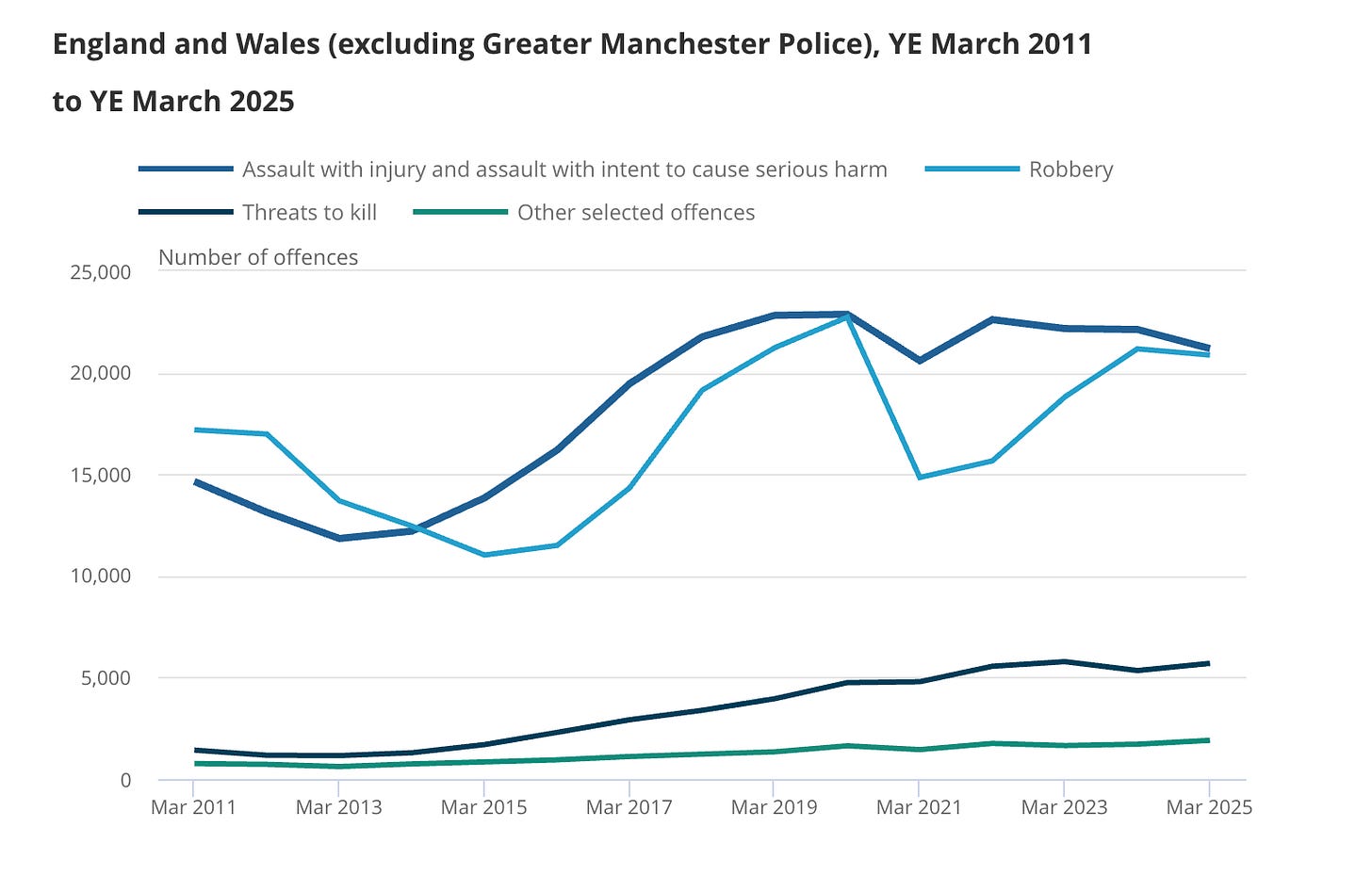

Offences involving a knife have fallen less sharply, but are still 1% down in the year ending March 2025 and 4% lower than the same period in 2020.

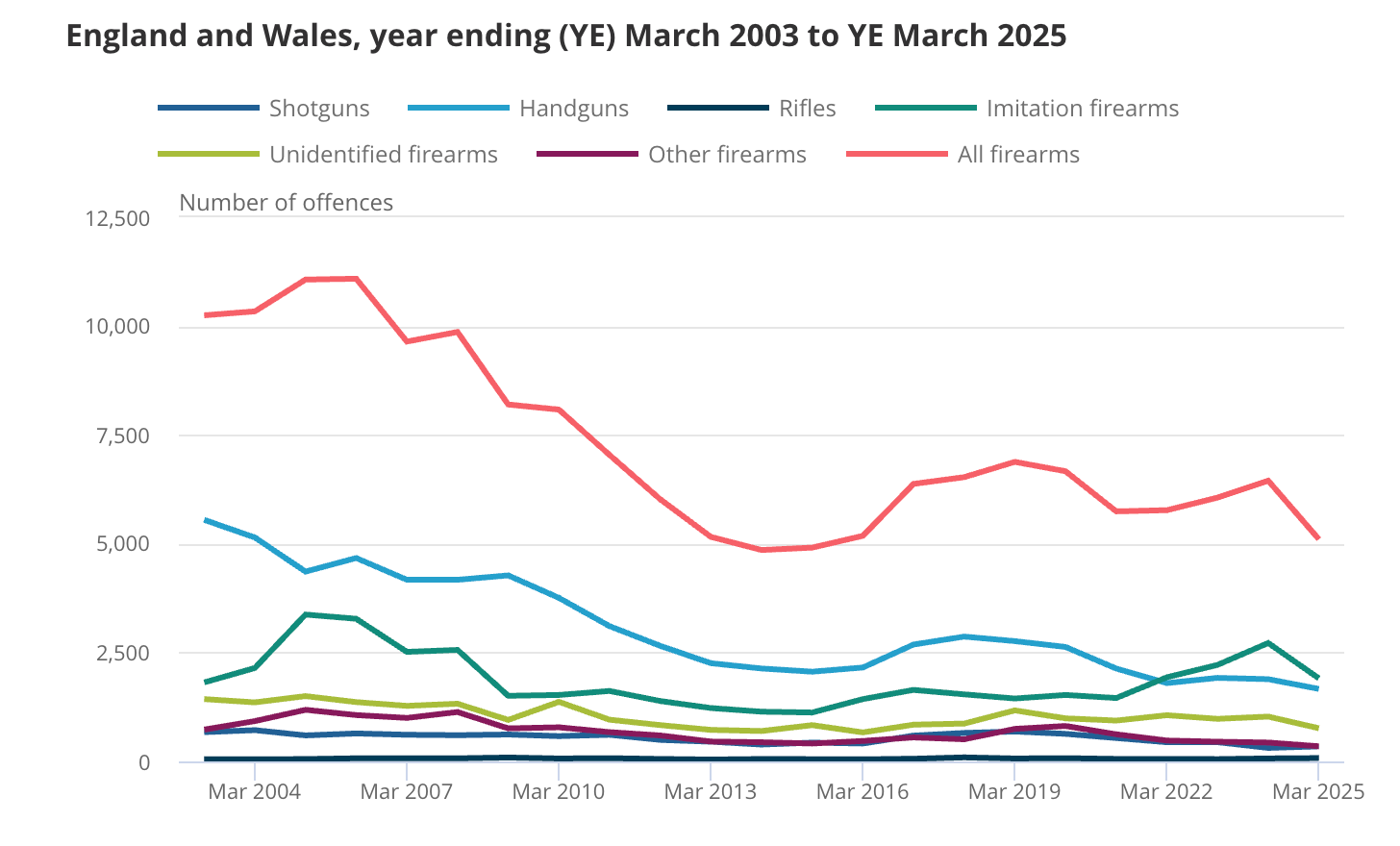

Offences involving firearms have fallen in the last year to their lowest levels since year-ending March 2015, and well below the mid-2000s.

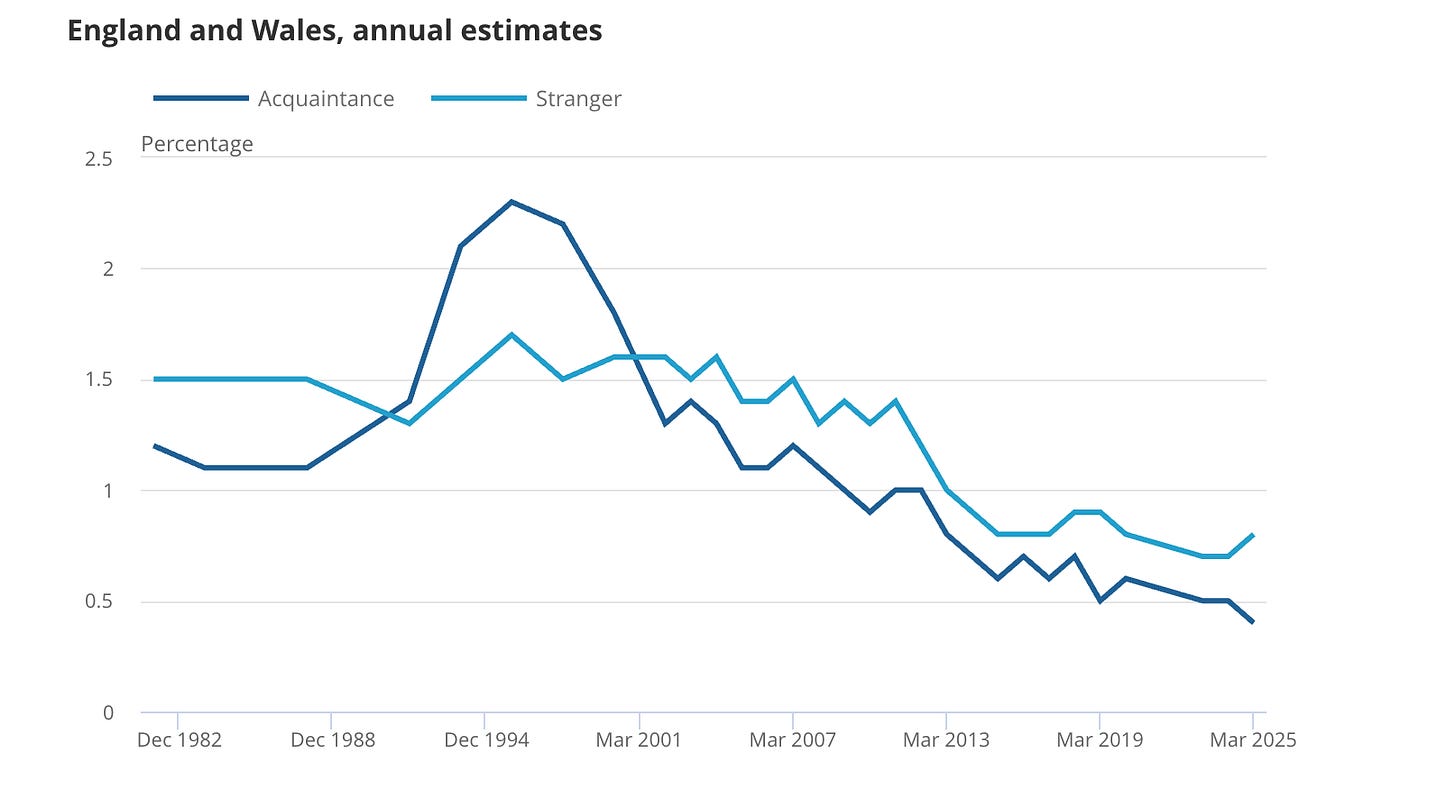

Violence has fallen:

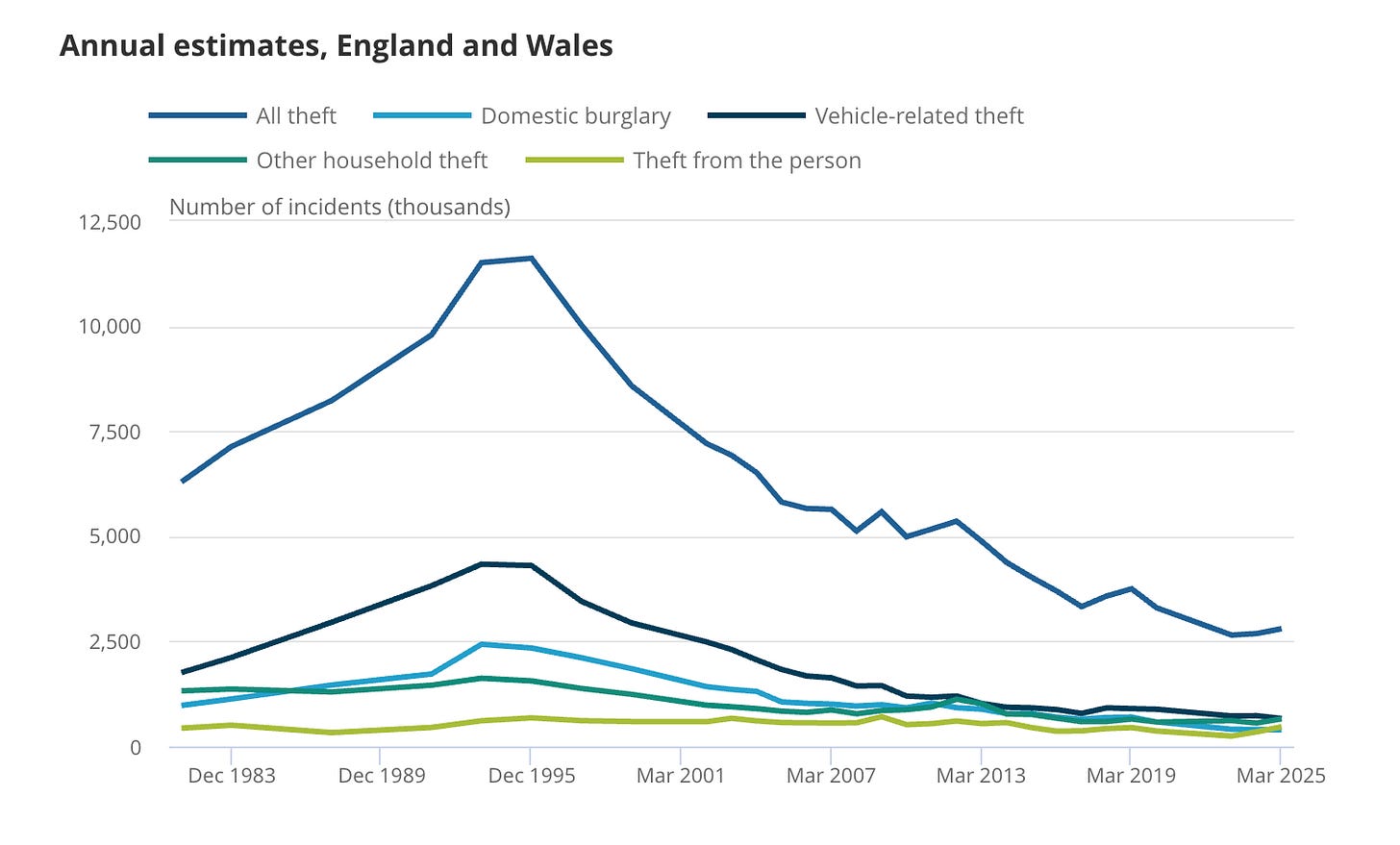

The Crime Survey even shows long-term reductions in incidents of theft, albeit with a 20% rise in incidents outside a dwelling compared to the previous year.

In response, Farage declared the CSEW “discredited” because it does not include shoplifting. That’s technically true — and shoplifting has indeed risen over the past year. But this is a misunderstanding, deliberate or otherwise, of what the survey is designed to measure.

The CSEW captures people’s personal experiences of crime, not offences against businesses or institutions. To dismiss it outright is to reject one of the most consistent and rigorous tools we have for understanding long-term crime trends. But it is helpful for those looking to exploit and encourage widespread disenchantment.

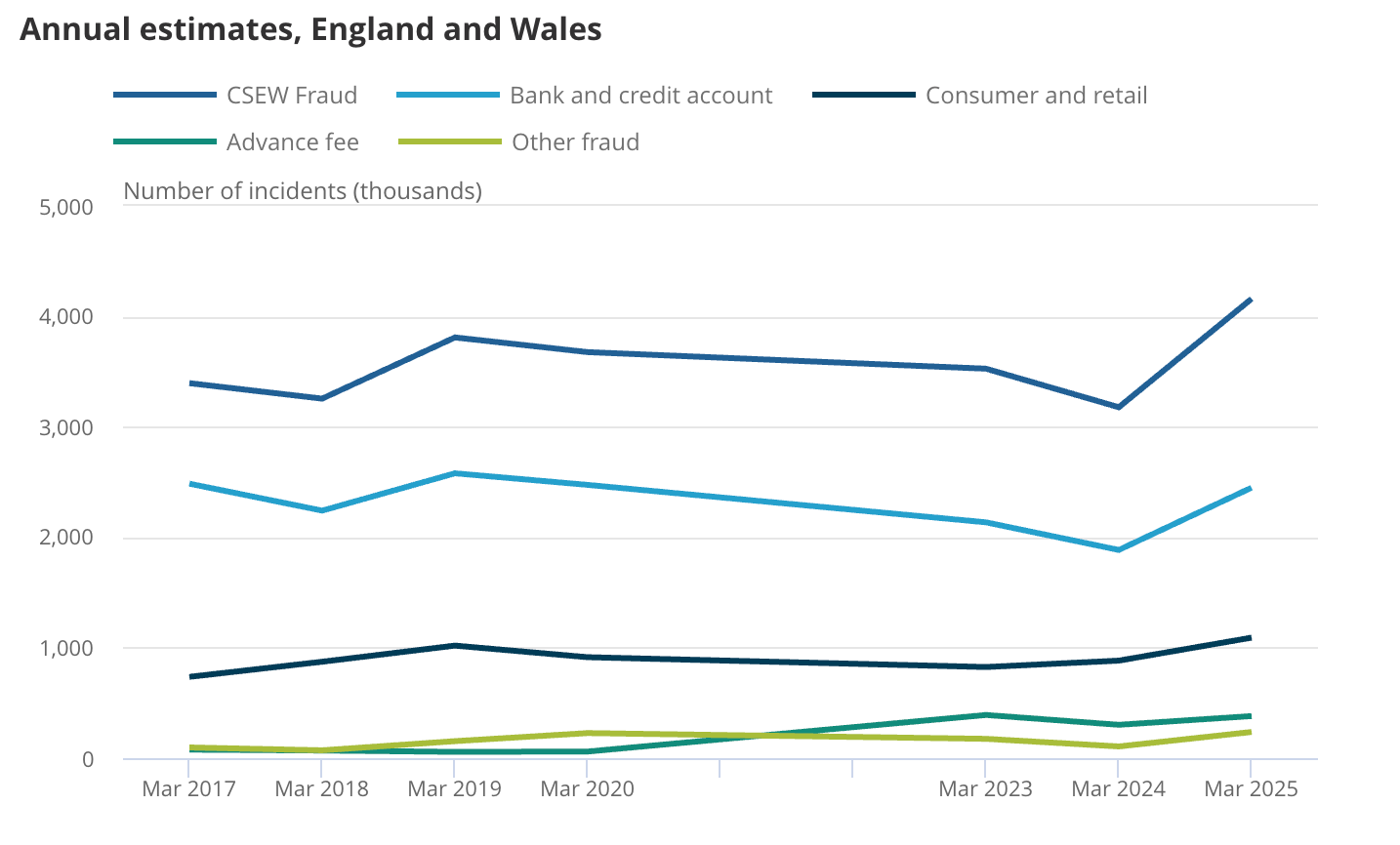

The CSEW shows around 9.4 million incidents of crime, a 7% increase compared with the same period the year before. But this is largely driven by a 31% rise in fraud to roughly 4.2 million incidents, the highest estimated figure since fraud was first collected in the survey in 2017.

Much of this is itself a result of a 30% increase in bank and credit account fraud (to about 2.4 million incidents), alongside an estimated 1.7 million incidents of consumer and retail fraud, advance fee fraud and other types of fraud — a staggering 88% increase compared with the same period of the 2017 survey.

I do not mean to dismiss violent crime or its seriousness. Moreover, we all take sensible precautions when we go outside. I am careful where and when I take my phone out, whether it feels safe to hold my husband’s hand or appear identifiably Jewish. But Farage et al. give the impression of still panicking about stolen car radios.

Some of the fastest growing threats we face today are not on the streets or dark alleyways but in our inboxes, dating apps and text messages. If politicians really wanted to be tough on crime, and not just stoke the fear of crime, they would go after the scammers who make every digital transaction feel like getting in a stranger’s car or engaging in any sort of contact sport after the age of 35.

There are important exceptions, such as sexual assault

He must be a very lucky man ;-)