Starmer risks U-turning without a destination

You can't reverse your economic project if you don't have one

“It’s alright to change your mind.” My mother has passed down plenty of advice over the years, some of which I’ve even listened to. But this is the one I remember most, and most fondly. It is a remarkably versatile adage. For balance, my father’s greatest piece of counsel came when he turned to me, seemingly apropos of nothing, and announced: “Jack, if you can avoid it, never take the M25.” I think between the two of them, I might have had access to the font of all human knowledge.

While I don’t know how Keir Starmer would choose to drive between Potters Bar and Dartford, he clearly knows when a change of direction is required. Responding to an assiduously planted question from Labour MP Sarah Owen at PMQs yesterday, the prime minister said he wanted to “ensure that more pensioners are eligible for winter fuel payments”. This represents, of course, a U-turn.

The decision to restrict winter fuel payments1 to those entitled to pension credit and other means-tested benefits was one of the first made by the new Labour government, before even the Budget. The change was estimated to save around £1.5bn, but the political messaging was clear: this was a government that had inherited a "£22bn black hole” and would need to make difficult and at times unpopular decisions to put things right. Yet as time has gone by, the prime minister and his chancellor have come under increasing pressure to change tack.

U-turns make headlines, but they are not usually a big deal. Turning around is almost always preferable to pressing ahead in the wrong direction. Indeed, the 2010-15 coalition government — in policy terms the most successful of the five Conservative-led administrations of the period — did it rather frequently. In no particular order, David Cameron and George Osborne U-turned on:

Plans to sell off the forests

The pasty and caravan taxes

The cap on tax relief on charitable donations

Minimum unit pricing for alcohol

Lobbying legislation

Raising fuel duty

This is by no means an exhaustive list. But what the government did not do is U-turn on its entire economic project. That Gordon Brown and his lackeys now leading the Labour Party, Eds Miliband and Balls, had crashed the economy, left no money, and that this government was cleaning up the mess, cutting the deficit and capable of setting out a long-term economic plan2.

When Margaret Thatcher rejected calls in 1980 to U-turn with a play on words that clearly had to be explained to her, she was ruling out reversing her whole political project. That is, the policy of market liberalisation and squeezing inflation out of the economy at the cost of, amongst other things, higher unemployment.

It was a repudiation not only of Labour and the economic establishment, but also of her predecessor as Conservative leader, Ted Heath. It was Heath who elected to ditch his free-market policies in the face of rising prices and industrial action. Had things gone differently, we might have ended up with something called Heathism rather than Thatcherism.

U-turning on his governing philosophy is not what Starmer has done. Winter fuel payments are small beer as far as the quantum of government spending is concerned. Indeed, the cuts to welfare announced at the Spring Statement last year are worth many times more. But the reason why the prime minister cannot be said to have U-turned on his broader economic strategy is that… it is not entirely clear he has one.

Starmer is shifting the country closer to Europe, but with firm red lines on free movement of people, the economic benefits will be limited. He is, thus far, refusing to raise the broad-based taxes necessary to funnel the sort of money into the public services that voters might actually notice. Worse still, there are cuts to come to unprotected departments such as justice, local government and even universities.

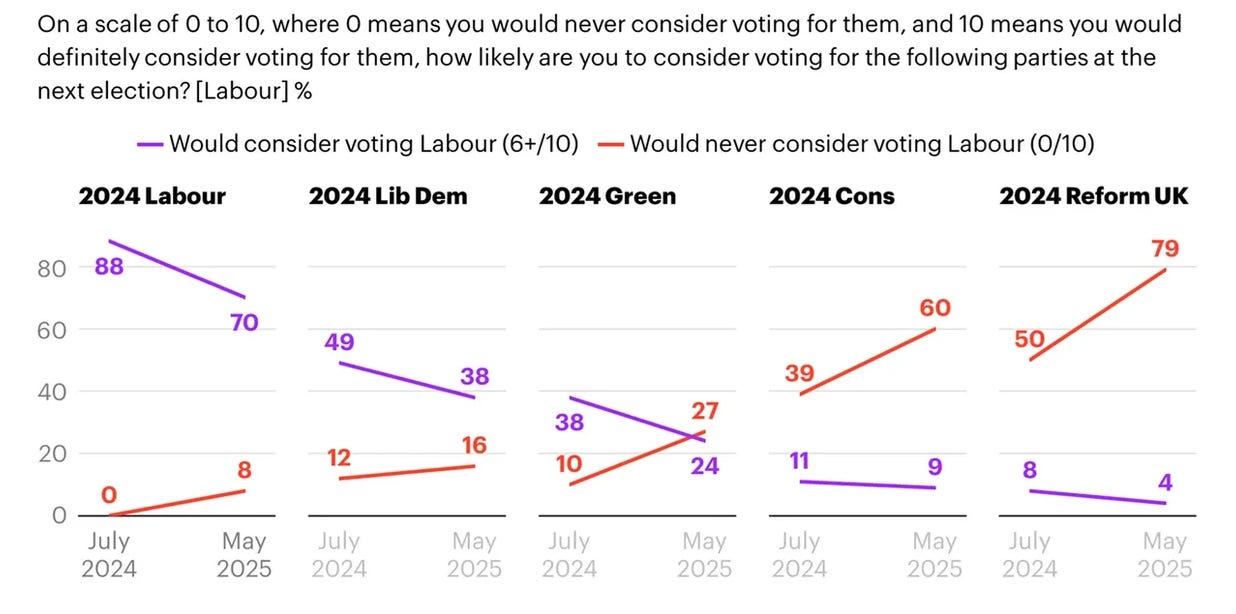

The political project is similarly cloudy. The focus on immigration has contributed to the alienation of Labour voters while not being nearly tough enough for Reform UK supporters. Polling by YouGov finds that only 4% of Reform UK voters say they would consider voting Labour in future. Fully 79% stated they would never consider voting for the party.

Meanwhile, Labour’s 2024 vote (already remarkably low for a landslide majority government) has fragmented. Just 46% are still with the party, while 12% have gone to the Liberal Democrats and 9% to the Greens. That is, to Starmer’s left.

Perhaps none of this will matter. The Tories — the most successful political party in the history of democracy — are currently a dodgy haircut away from polling fifth. Reform UK are unproven and distinctly off-putting to great swathes of the electorate. The Greens are having a mid-parliament crisis of their own. Meanwhile, Labour and the Lib Dems have not unlearned the peaceful coexistence that made 2024 such a triumph for both parties. Still, it is one heck of an oversight.

In politics, as in life, course corrections are often necessary — even admirable. But without a clearly articulated destination, U-turns begin to feel less like nimble navigation and more like aimless drifting. Governing by focus group — and trimming the sails of the state when the wind shifts — will only carry a government so far.

At some point, the question won’t be whether Labour is more competent than the Conservatives or less repellent than Reform UK. It will be whether anyone knows who it is for and what it is actually trying to achieve.

A cash lump sum of £200 a year for households with a pensioner under 80, or £300 for those over 80

Remember the long-term economic plan?